This post was originally published on this site

When I unretired from my full-time job as an editor in 2022, I thought I had a pretty good idea of what to expect. I hadn’t counted on ageism.

Turns out, ageism is all around us — in the media, at the doctor’s office, in the anti-aging products in drugstore aisles and in our daily conversations.

As William Kole notes in his new book, “The Big 100: The New World of Super-Aging,” University of Michigan researchers found that among people they surveyed, eight in 10 respondents ages 50 to 60 said they’d encountered one or more forms of everyday ageism.

I heard a lot about the scourge of ageism at a recent symposium at which I was a speaker. The event — Dismantling Ageism: How Stereotypes, Prejudice and Discrimination Based on Age Affect Us All — was held a day after Ageism Awareness Day, which falls on Oct. 7.

Ageism is invisible and taught

“Ageism is really invisible,” the symposium’s keynote speaker, Tracey Gendron, said. Gendron is the chair of the department of gerontology at Virginia Commonwealth University. ”Ageism is not innate. It is taught.”

It also makes people feel invisible — along with depressed, disrespected, devalued, marginalized and overlooked, said Kris Geerken, co-director of the Changing the Narrative anti-ageism initiative. “Research shows that ageism can shorten our life span by seven and a half years, accelerate cognitive decline [and] increase anxiety and depression.”

Sometimes, even those of us who are ourselves in the second half of life can be a little ageist without even thinking about it. It’s easy for us to fall into the traps of ageism, Gendron said.

Read: Retirees tend to be happier than younger people — even if their finances aren’t great

Falling into ageism traps

During her presentation at the symposium, Suzanne Kunkel, a senior research scholar at the Scripps Gerontological Center of Miami University, admitted her own experience falling into an ageism trap.

Kunkel told the audience that she had asked her grandson who he thought was older, her husband or her. When he gave the wrong answer, she said she’d tell her husband because he’d think it was funny. Her grandson’s reply: “Why is that funny? Is it bad to be old?” That taught her a few things, she said.

Geerken gave a few other examples of interpersonal ageism and internalized ageism.

Interpersonal ageism includes things like “elderspeak,” when you are talked down to because of your age. Some doctors, for example, do this when they minimize health symptoms by saying the patient is “just getting older.”

Internalized ageism is what we’re guilty of when we say things like “I’m having a senior moment” or “I’m too old to change my habits or learn a new technology,” Geerken said.

Sometimes we’re aware of what we’re saying, but sometimes we’re not.

Read: ‘Aging in place has a shelf life’: What this eldercare expert wants you to know.

Ageism in retirement

Ageism can be especially pernicious, I think, once you retire and some people start thinking of you differently.

I’m continually surprised when I’m arranging an interview for an article and the prospective interviewee says: “I thought you were retired!” — as though I had retired from life.

We — and society — can reduce ageist views of retirement by realizing, as Gendron puts it, that “retirement is a social institution. It tells me you used to work in a job full time, but not who you are and who you are becoming.”

It’s cool, she said, to say “I’m retired, and this is who I’m becoming.”

Read: Should you start a business in your 50s or 60s? Here’s how to find financing and build a new career.

Measuring your own ageism

To help understand age bias, Kunkel and her fellow researchers have crafted a clever tool called the AgeSmart Inventory, which has 35 age-related statements. You respond to each one, noting whether you agree or disagree, to help you detect your own age biases. She shared a few of the statements with the symposium audience:

“Older people really need to retire to make room for others.”

“In my experience, older people have a hard time learning new things.”

“I feel better and better about myself as I grow older.”

“I think that the elderly deserve our respect and admiration.”

One member of the audience said the first statement resonated because she has been told that older people need to retire to make room for others. “I just smile and say, ‘It’s not going to happen,’” she said.

The symposium audience and I felt that last statement — “I think that the elderly deserve our respect and admiration” — was something of a trick.

Respect and admiration are kind, but the word “elderly” is ageist because it connotes frailty and wrongly stands in for all older adults.

Tracey Gendron

How to disrupt ageism

It’s up to all of us to disrupt ageism and to push back when we see or hear it.

If someone says something ageist to you, Gendron said, “respond by saying: ‘I don’t like that — it’s offensive.’ Or, ‘What do you mean by that?’”

She added: “Make the invisible visible.”

Watch yourself, too, she advised. “Take a moment to pause and reflect and consider if your words or actions are contributing to ageism, and then act to steer the narrative of ageism,” she said. “Remember: We are all role models for aging.”

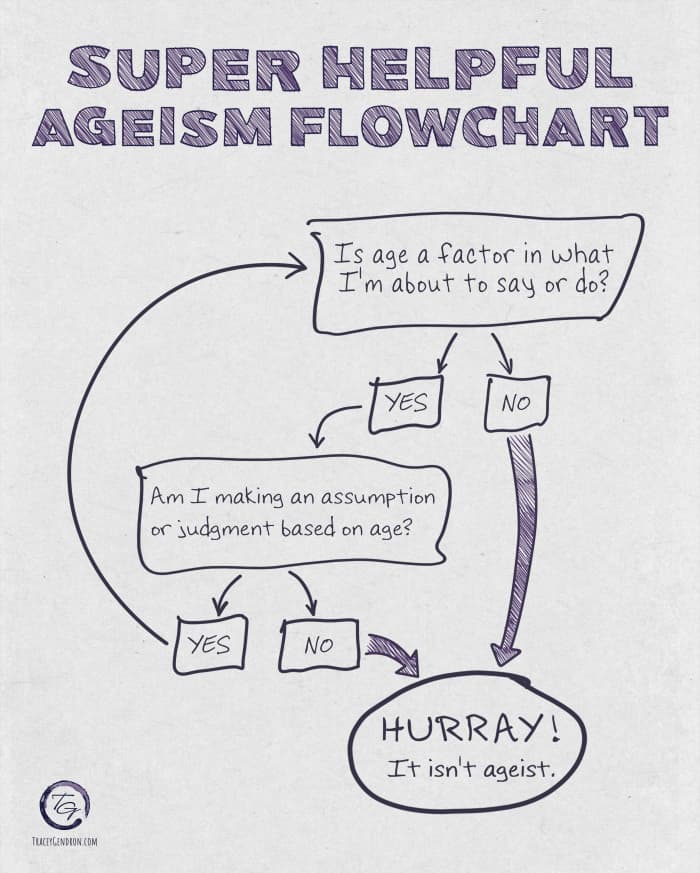

The “Super Helpful Ageism Flowchart,” which she created and showed at the symposium, might be helpful. As the graphic shows, if age is a factor in what you’re about to say or do and you’re making an assumption or a judgment based on age, you’re being ageist.

“People do not lose the assets that they accrued over their lifetime. Their expertise and experience and ability to use those in novel situations leaves them actually better prepared to problem solve in ways that younger people don’t have a background to be able to do,” Linda Fried, dean of the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, recently said on MSNBC.

I’m trying to fight back against my unconscious ageism and to make visible the evidence of ageism I encounter. I hope you will, too.