This post was originally published on this site

You can significantly improve your investment performance by expanding your definition of corporate profitability.

New research finds that Wall Street has been using a restricted definition of return on equity. As a result, individual investors and professionals both have unwittingly been shunning the stocks of companies that in fact are highly profitable while favoring companies whose profitability is relatively unimpressive.

This limited definition of profit overlooks corporate expenditures on intangibles, such as research and development (R&D). Traditional accounting practice for decades has been to “expense” anything spent on intangibles — thereby reducing dollar for dollar what otherwise would be reported as profit.

The study that found there’s a better way of calculating profit, entitled “An Intangibles-Adjusted Profitability Factor,” was conducted by Ravi Jagannathan and Robert Korajczyk, both finance professors at Northwestern University, and Kai Wang, a postdoc at that institution.

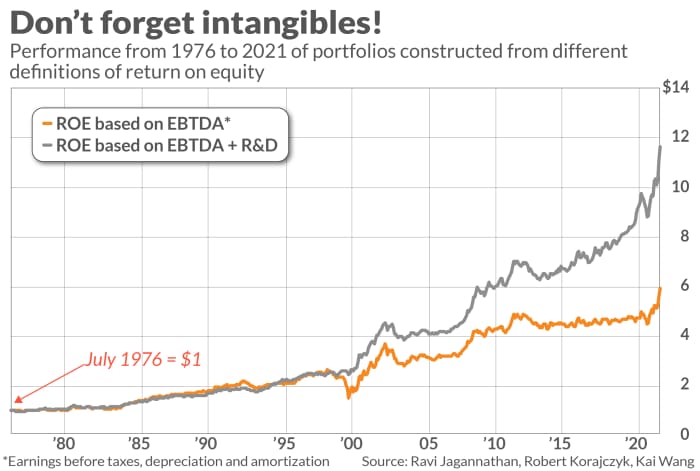

To illustrate, consider two hypothetical portfolios they constructed out of stocks with the greatest profitability. The first used a traditional definition of profit to determine which companies to own, based on “earnings before taxes, depreciation and amortizations”, or EBTDA. The second portfolio used the expanded definition to include both EBTDA and R&D, and it significantly outperformed the first — as you can see in the chart below.

This new study is not the first to find that the traditional accounting treatment of intangibles leaves much to be desired. But, Jagannathan said in an interview, most prior studies focused on intangibles’ impact on book value rather than on earnings. Those studies were primarily of interest to value-stock managers, who rely heavily on the price-to-book-value ratio when determining which stocks are most undervalued.

This new study finds that, in addition to adjusting book value to incorporate intangibles, it’s also important to adjust our definition of profit. Since pretty much everyone on Wall Street focuses on profitability, this new study’s findings will be nearly universally relevant to all of Wall Street.

Another of the study’s findings sure to get Wall Street’s attention is the relationship between intangibles-adjusted profitability and momentum — the tendency for a stock that has recently beaten the market to continue doing so for a while longer.

Jagannathan said that momentum strategies no longer add value once companies are sorted using the intangibles-adjusted definition of profitability.

This result doesn’t mean that momentum no longer works, Jagannathan said. Instead, it provides a possible explanation for why momentum works, which has been largely a mystery.

Consider two companies with identical profitability according to traditional accounting practices, but the first spends heavily on R&D and the second spends none. You’d expect the first company’s earnings to grow faster in subsequent years than the second, and for the pace of its earnings growth to accelerate as its R&D expenditures begin to pay off. Without focusing on intangibles-adjusted profitability, however, this first company’s accelerating earnings-growth rate can be hard to determine.

How to take intangibles into account

Generally-accepted accounting principles don’t provide for a separate line item on a company’s income statement for intangibles. Estimating their magnitude requires making an assumption about what portion of the line item for “Sales, General & Administrative Expenses” (SG&A) should be included. After testing a number of different possibilities, the authors of the study found that the best estimate of intangibles is to combine R&D expenditures together with 30% of SG&A expenditures other than R&D.

Jagannathan provided the following table as an example of this approach, focusing on data from Amazon.com’s

AMZN,

10-K for the period ending this past December. As you can see, Amazon’s return on equity jumps dramatically after intangibles are taken into account.

| Line | From Amazon 10-K 12/31/2022 | $ Millions |

| 1 | Earnings before taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBTDA) | 35,982 |

| 2 | R&D (listed as “Technology and Content” in 10-K) | 73,213 |

| 3 | SG&A excluding R&D | 139,691 |

| 4 | 30% of SG&A (0.3*line 3) | 41,907 |

| 5 | EBTDA + R&D + 0.3*SG&A (lines 1+2+4) | 151,102 |

| 6 | Total shareholders’ equity | 146,043 |

| ROE based on EBTDA alone (line 1 divided by line 6) | 24.6% | |

| R&D Adjusted ROE (line 5 divided by line 6) | 103.5% |

The implication of this table’s data is that Amazon could report much higher profitability if it were not to spend as much on R&D and other intangibles. But if it were to do so, it would be forfeiting the increased future profitability that comes from R&D. The point of this new study is, in essence, that financial analysts should take intangibles into account and not give companies an incentive to take from the future in order to boost current-year profits.

A return on equity of over 100% certainly looks impressive. But in order to really know how Amazon’s profitability would rank, you’d have to go through a similar process for all other publicly-traded companies — a huge undertaking. That’s what the authors of this new study did to reach their results for the period 1976 through 2021.

Jagannathan said he’s not aware of any firm that currently updates a ranking of all stocks according to their intangibles-adjusted profitability. But, given the impressive results they found for this adjustment, it’s a good bet that one or more firms will start to do so. Until then, we won’t know which company in the market has the highest adjusted-return on equity.

But we don’t need to know that to still take the study’s findings to heart. When we analyze an individual company and compare it to another, it shouldn’t be particularly onerous to duplicate the analysis that Jagannathan illustrated with Amazon. Upon doing that, and if all else is equal, you would want to choose the one with higher intangibles-adjusted profitability.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: 3 S&P 500 sectors say a new bull market is near. These 8 stocks are top picks.

Also read: You’re probably missing out on recent gains from non-U.S. stocks. Here’s why that needs to change.