This post was originally published on this site

The financial market’s first-half fear of an imminent U.S. recession is in the process of being replaced by a new storyline: One which features what one Goldman Sachs strategist calls a “latent” risk of an economic downturn in the next 12 months and a perhaps not-so-hard landing, as central banks keep hiking rates to curb inflation near 40-year highs.

At Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

GS,

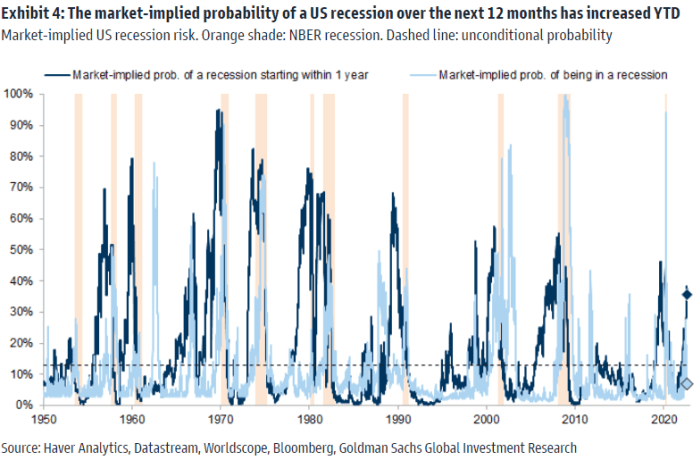

researchers put the market-implied risk of a U.S. recession starting within one year at a year-to-date high of 37% as of Thursday, as shown in the chart below. And while the threat of stagflation hasn’t gone entirely away, it may look something more like “quasi-stagflation” or an environment with “stagflation tendencies,” said Christian Mueller-Glissmann, a managing director and London-based head of asset allocation for Goldman Sachs.

Sources: Haver Analytics, Datastream, Wordscope, Bloomberg, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

Underlying the latest shift in thinking is the notion that the U.S. economy may be better equipped to handle higher rates than previously thought. Signs of that sentiment change have been most evident in U.S. stocks, which have bounce back from their mid-June lows and even eked out slight gains on Thursday despite divergent comments by Fed officials on interest rates. The shift stands in contrast to the pessimism that prevailed in the first half.

Goldman Sach’s conclusions came as U.S. stock and bond markets pivoted into a wait-and-see mode for much of Thursday, even after Federal Reserve officials came out with fresh remarks about the possible paths forward in rates. In Treasurys, “an environment of indecision” has prevailed as “investors put policy angst on hold in favor of sidelined positions until there is great clarity on how the employment and inflation landscape evolve in August,” said BMO Capital Markets rates strategists Ian Lyngen and Ben Jeffery.

Read: Fed doesn’t want to ‘overdo’ rate hikes, San Francisco president Daly says and Fed’s Bullard says he is leaning toward backing 0.75 percentage point hike in September

“In the first half of the year, markets had been really worried about the risks of imminent recession, because central banks have to fight this incredibly high inflation. That risk has gone down,” Mueller-Glissmann told MarketWatch via phone. “The problem is you can still have this traditional recession unfold, where central banks are tightening policy, yield curves are flattening, and there’s a growth backdrop that’s deteriorating for a few quarters.”

“A traditional recession takes time to build” and, in such a scenario, “you can expect earnings expectations to turn more negative,” he said. “That latent risk over the next six to 12 months is the same or higher than it was before. Our base-case view is that if we get a recession, in most economies it’s likely to be pretty soft; the only place where it would be deeper is Europe. But that doesn’t change the view that one of the steepest rate-hiking cycles on record will likely hit earnings and that markets will have to reprice risk.”

On Thursday, Dow industrials

DJIA,

the S&P 500

SPX,

and the Nasdaq Composite COMP

COMP,

were up by 13.8%, 16.8% and 21.8%, respectively, from their mid-June lows. The S&P 500 and Nasdaq finished the day up by 0.2% each, while Dow industrials gained less than 0.1%.

In foreign-exchange markets, the pricing of major currencies like the dollar is still “closely anchored” to stagflation and recession as the most likely outcomes, and the dollar is trading as a “superb” hedge against the risk of high inflation and slower growth, said Mark McCormick, global head of FX strategy for TD Securities in Toronto.

Those risks “have not been fully priced out yet in the dollar” and people are still long the dollar because “a deterioration of growth in Europe and Asia at the same time are powerful forces that the dollar responds to,” he said. Given a roughly 13% year-to-date rise in the ICE U.S. Dollar Index

DXY,

the greenback “is not priced for a softish landing, it’s priced for a contraction in the global economy and the question is how much the U.S. contributes to that weakness.”

“If things evolve into a better state in the next six months — China recovers, Europe produces fiscal stimulus — and 2023 looks a lot better, the dollar will look very expensive, given its stagflation properties heading into what could be a better world,” McCormick said.