This post was originally published on this site

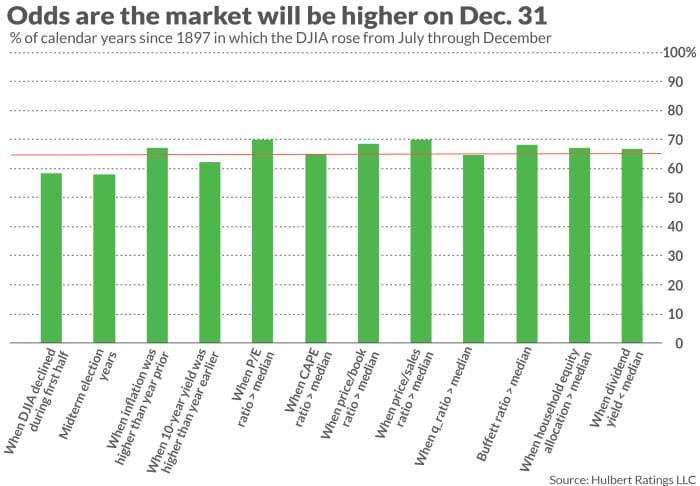

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. — There’s a two-out-of-three chance that the stock market will rise through the end of this year.

Before you get too excited by these odds, however, you should know that the same odds exist at the mid-point of every year. They stay the same regardless of how much the market has risen or fallen over the first half of the year, or the status of any of a myriad other indicators that investors typically look to when betting on the stock market’s intermediate trend.

I am taking the occasion of 2022’s halfway mark to remind you of this in order to counter the widespread tendency to detect patterns when in fact none exist. Some will argue that a bad first half of the year dooms the second half to a similar fate. Contrarians will assert the opposite. Neither position is supported by the data.

That’s because the stock market is forward looking. Its level at any given time will reflect all publicly known information up to that point. So if the stock market falls during the first half of the year, as it most definitely has in 2022, with the S&P 500

SPX,

down 23%, or when inflation is heating up, as it has over the last several months, that will already be reflected in stock prices. The same will be true for interest rate trends, market valuation, and where we stand in the Presidential Election Year Cycle.

This doesn’t mean that these factors are irrelevant. It just means that, to the extent that they impact the market’s

DJIA,

odds of rising or falling, the market will already have gone or up or down before we reach the year’s halfway mark.

Imagine, for sake of discussion, that a bad first half increases the odds of a bad second half. If that were the case, traders would immediately reduce their equity allocations rather than wait until June 30 to do so. Their sales would reduce the stock market’s level, which in turn would increase the odds that it rises in the second half. This adjustment process would come to an end when the odds of a gains for the second half of the year are no worse than they would otherwise have been.

A similar dynamic, but in reverse, would come into play if a bad first half increased the odds of an above-average second half. In that case traders would immediately increase their equity investments, and their purchases would bid up the stock market’s level until the odds of a rising second half came back down to be no higher than otherwise.

That’s the theory, anyway. And it’s impressive how close the real world lines up with this theory, as you can see from this chart. It shows the odds of the market rising between July and December as a function of a dozen separate variables. I picked these dozen because each applies to this year in particular.

Notice how close each of the odds is to the overall average. None of the differences is significant at the 95% confidence level that statisticians often use when determining if a pattern is genuine.

I said at the top of this column that you shouldn’t get too excited by the two-out-of-three odds that the market will be higher at the end of the year, since they apply to every year. But, in at least one sense, they are good news: Because the market’s level already takes into account all publicly known information, you can focus your analytical energies on estimating companies’ future profitability.

It’s hard enough divining the future without adding the additional headache of constantly looking in the rearview mirror and rehashing the past.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.