This post was originally published on this site

When Russian President Vladimir Putin launched his war against Ukraine, most observers predicted the conflict would end quickly with a Russian flag flying over Kyiv. Just as projections about the conflict have been exaggerated, so too are those forecasting the demise of globalization as an after-effect.

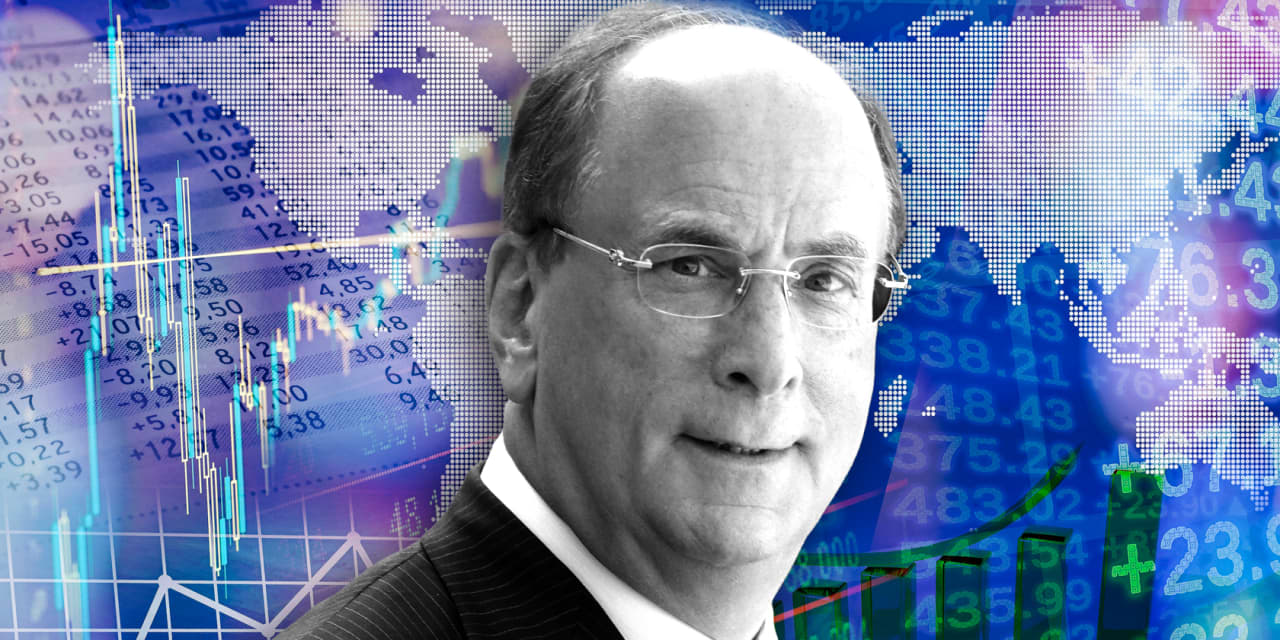

In his annual letter to shareholders, BlackRock

BLK,

CEO Larry Fink declared the invasion, “put an end to the globalization we have experienced over the last three decades.” As the head of the world’s largest asset manager, Fink’s argument may reflect the conventional wisdom across boardrooms of many Western companies.

While recent events, including the COVID-19 pandemic, have highlighted the vulnerability of global supply chains, discarding globalization as the proverbial baby with the bathwater would be an overreaction and grave mistake. Instead, companies need to diversify their supply sources, complementing remote sources with nearby North American or European facilities.

Long before Putin’s war, companies were already moving away from sourcing certain goods from a single-supply source. For example, Volkswagen

VOW,

VLKAF,

the world’s second-largest automobile manufacturer, has been steadily increasing its investments in Europe and the U.S. in order to dilute its dependence on the Chinese market and shore up its fragile supply chains.

Last year, Intel

INTC,

the global leader in the semiconductor industry, reversed a decades’ long strategy of outsourcing chip manufacturing to Southeast Asia. It committed to invest $20 billion in two Arizona plants and $40 billion for manufacturing facilities in Western Europe to reduce dependence on the politically volatile Taiwan, producer of 61% of the world’s semiconductor microchips.

Global companies have been waking up to the realization that price savings associated with offshore options are being offset by a host of factors, including long lead times resulting in large inventory costs or inferior service levels. Moreover, supply chains should be able to react quickly to changes in relative cost structures like labor and transportation costs, or the significance of each cost component, along with fluctuations in interest, currency rates and tariffs.

The cost of Chinese labor, for example, almost tripled between 2000 and 2016, while it barely moved in North America and Europe. The degree of automation, for example in the apparel industry, has greatly increased, reducing the importance of labor costs and hence the advantage of offshore facilities.

Recognizing this, this past decade has seen more U.S. companies move toward partial onshoring, a trend that the pandemic and Putin’s war have only accelerated. Many companies, including Adidas

ADS,

and Nike

NKE,

have opened “speed factories,” smaller North America based plants that supplement rather than substitute for large offshore facilities. Even the Chinese computer manufacturer Lenovo

992,

diversified its risks in 2013 by opening a facility in North Carolina.

Rather than betting on a single supply source, these and other companies are wisely applying a portfolio approach to supply sources, which provides them the ability to quickly alter supply channels in response to political, global health, and other volatilities. Colleagues and I showed exactly how this works in recent studies, demonstrating that companies can reduce costs and better meet consumer demands by sourcing even just 20% of their volume from a second, closer supplier.

Thankfully, national industrial policies are reinforcing these trends. Less than a month after taking office, President Joe Biden signed an executive order calling for more resilient supply chains and built in redundancies. In August 2021, he signed an executive order on preserving essential medicines that divides, “procurement requirements among two or more manufacturers.” And most recently, Biden agreed to boost U.S. sales of oil and gas to Europe as a way to reduce the continent’s dependence on Russian energy.

But executive orders have little long-term impact and are susceptible to the whims of changing presidential administrations. They must be paired with concrete legislative action. In June 2021, the U.S. Senate passed the Innovation and Competition Act (USICA) by a bipartisan 68-32 vote. The bill included $52 billion for the CHIPS Act to assist domestic semiconductor production. The measure has since stalled in the U.S. House of Representatives, leading Intel to take its business to Western Europe instead.

Bringing overseas jobs back to the U.S. is not only good company policy, it also is good politics for officeholders on both sides of the aisle seeking re-election in these populist times. Global trends have highlighted the need to diversify global supply chains, and discerning companies have started acting accordingly. Now American leaders need to act to enable globalization’s reform for the 21st century.

Awi Federgruen is the Charles E. Exley Professor of Management and Chair of the Decision, Risk and Operations Division of the Columbia University Business School.

More: Larry Fink says globalization is over — Here’s what it means for markets