This post was originally published on this site

Tracy James, a Pensacola, Fla. healthcare industry recruiter, is stuck on $57. That’s how much she paid Sunday to fill up her Nissan Altima, when it was already a quarter-tank full. Fear crossed her mind when she saw the price: “If it’s more than this, what are we going to do?”

James, 52, had a labor of love packed in her work schedule — a drive from one side of town to the other to pick up or drop off her grandson at his pre-kindergarten class two or three times a week. It’s been roughly two weeks since she’s done it. “I haven’t been able to help like I have been. It’s a strain for us as a family to have to do that,” she said.

In a time of record-breaking gas prices, many Americans like James have a particular number stuck in their mind. It’s a number that’s upending their routines and becoming a source of disbelief, fear and anger.

‘If it’s more than this, what are we going to do?’ It cost Tracy James $57 to fill up her Nissan Altima from a quarter-full tank.

Photo courtesy Tracy James

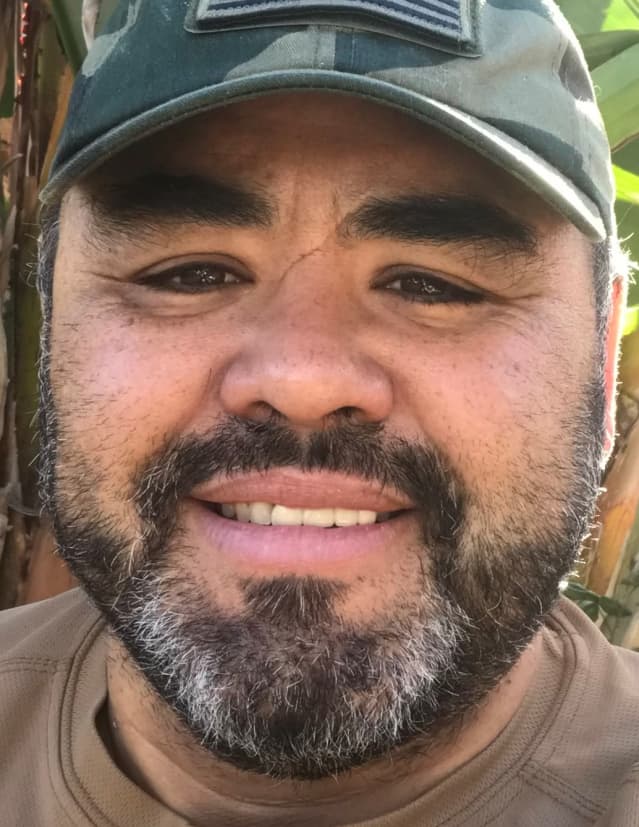

For Teaneck, N.J. resident Danny Reyes, the number is $61. That’s what he paid Monday to gas up his Kia Sorrento. “I felt like ‘Oh wow,” said the part-time Amazon

AMZN,

driver with his own blog, Swaggerdad.com. “My head is turning.”

The lease on Reyes’ SUV is up at the end of 2023. He’s already researching electric vehicles. Over the weekend, he started carpooling with a buddy to get to their longtime Saturday morning football game in Manhattan. When his friend brought up the carpool idea to try saving some bucks, Reyes, 51, was an easy sell. “I was like, ‘Say no more.’”

The carpool for his son’s basketball practice started before the steep price jumps as a nod to time management, but Reyes said the shared rides are more important than ever now.

For Moises Godoy, an English teacher in the suburbs of San Diego, Calif., the scary number is around $130. That’s what he paid Tuesday to fill up his Chevy

GM,

Silverado. Actually, Godoy first paid $12 to eke out two gallons at a nearby gas station.

That was enough to get him over to the discount store Costco

COST,

and its cheaper gas prices, where he paid the $130. Godoy had to wait in line for 35 minutes because so many other drivers had the same idea on where to get the best (relative) bang for their buck.

‘Now when we are going to places, we calculate if it’s worth it or not,’ Danny Reyes said. He recently spent $61 filling up his car in New Jersey.

Photo courtesy Danny Reyes

“It doesn’t feel right. It feels like we’re being robbed,” said Godoy, 51. He says he has to be a lot more “intentional” now about when and where he drives, grouping chores and trips in the name of fuel and money conservation.

For two years, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced many Americans to think hard about where they went and how they lived their daily lives. More than two weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine and sent already-rising crude oil prices into overdrive, they are increasingly factoring gas price jumps into their decisions as COVID-19 infection counts drop.

The increased prices are happening at a time when decades-high inflation rates have been sticking around — and when more employers want their workers commuting so they can be physically back in the office.

When do gas prices affect behavior?

On Wednesday, AAA said the national average for a gallon of gas was $4.25. One day earlier, prices beat the all-time record of $4.11, set in July 2008.

When gas prices hit the $4 mark, drivers increasingly think about fuel-saving tactics such as reducing their travel, grouping chores and carpooling. When they surpass $5, drivers increasingly follow through on those measures, a AAA spokesman said.

Consumer purchasing power and fuel efficient vehicles may take a little sting out of sticker price shocks, some say. But the gas price numbers that people see and pay regularly carry psychological weight, said Haverford College economics professor Carola Binder.

“When gas price rises, consumers get more pessimistic about the overall economy,” said Binder, who’s studied the interplay being Gallup polling data and retail gas prices.

Drivers haven’t started limiting car trips — yet

From here, the question becomes how much drivers’ behavior will change, how long it will last and how much deeper consumers will have to dig into their wallet.

So far, higher gas prices aren’t translating into fewer car trips, said Bob Pishue, transportation analyst at INRIX, a traffic and mobility data analytics company. Nationally, vehicle trips were up 20% last week compared to a January-February 2020 baseline, according to Pishue. “If it’s had an effect, it’s had a relatively small effect on driving,” Pishue said.

What happens in the future remains to be seen, he noted. But if current driving patterns hold amid higher gas prices and more people commuting to offices, the result will be more people paying more money on gas, Pishue said.

‘It doesn’t feel right. It feels like we’re being robbed,’ said San Diego resident Moises Godoy. He recently waited in line for more than half an hour for relatively cheap gas at Costco.

Photo courtesy Moises Godoy

Transportation costs have been the second biggest part of household expenses for a long time, according to Department of Agriculture data. Housing is the biggest piece, accounting for roughly one-third of expenditures, from 1997 to 2020, the data showed. Transportation costs have ranged between roughly 19% and 15%, with 2020 transportation costs making up 16% of household expenditures.

Food, the longtime third-biggest expense, was 11.9% of the household budget in 2020, the data noted.

Keep in mind 2020 numbers don’t capture the impact of months of red-hot inflation in 2021 and 2022. In January, the cost of living increased 7.5%, Bureau of Labor Statistics data showed. Gasoline costs jumped 40% year-over-year that month.

If reduced travel isn’t showing up yet in big-level data, that doesn’t mean it’s not happening.

Almost half (45%) of drivers said they were shortening driving lengths to cope with rising gas prices, according to a recent Autoinsurance.com poll of 1,520 people from European countries, the U.K. and U.S. (Just over 500 survey participants were American.)

Reyes said he and he wife like to enjoy the views and walks at a New York State park roughly 40 miles north. That’s not happening for now, he said. “Now when we are going to places, we calculate if it’s worth it or not,” he said.

In Pensacola, James and her husband like to travel when they can, to sightsee and enjoy restaurants. Something like a recent three-hour ride to Birmingham, Ala. would be off the table now, she said.

The real hurt comes from the skipped trips to see her grandchildren. It’s a special pang for a woman who wants to be there as much as she can for her daughter and son-in-law, as well as her 4- and 8-year-old grandsons, both with special needs. Her 8-year-old grandson is homeschooled and James has also — until recently — been able to occasionally bring him to her place to help with schoolwork and put some variety in his week.

The good news is her daughter and son-in-law are planning to move much closer to her in the spring, James said. Rising gas prices helped their moving decision, James said.

But that’s then and James has to stick with her budget now. “As a grandparent, it really makes you feel you are not adequate enough. … It’s kind of depressing I can’t do that now.”