This post was originally published on this site

The benefits of the landmark small-business relief program designed at the height of the pandemic mostly went to business owners rather than workers, a study from leading economists finds.

The study from authors including famed Massachusetts Institute of Technology economics professor David Autor, as well as several Federal Reserve economists, examined the $800 billion Paycheck Protection Program. It was circulated by the National Bureau of Economic Research, and tapped into data from payrolls processor ADP.

The PPP initially was signed into law by President Donald Trump in April 2020, and President Joe Biden signed an extension in March 2021. Both the initial law and the extension were overwhelmingly bipartisan.

The far-reaching PPP ended up sending loans to approximately 93% of small businesses, in just two months. The end result, the authors estimate, is that the program preserved up to 3 million “job years” of employment at a cost of between $170,000 to $257,000 per job-year retained.

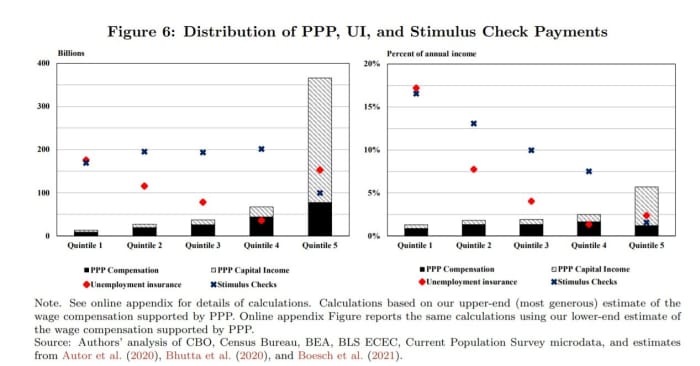

Put another way, between 23% to 34% of PPP dollars went directly to workers who otherwise would have lost jobs, the study found. The program also was highly regressive, with three-quarters of PPP funds accruing to the top quintile of households.

The authors said PPP did help keep the lights on at establishments that otherwise would have shut, though they don’t know whether that was a permanent or temporary impact. PPP loans helped reduce employment losses due to small-firm closures by about 8 percentage points five weeks after loans were received, the authors said.

Another finding was that so-called second-draw loans in 2021 — that is, companies going back for more funding a year later — had no impact on employment. The authors said that was “perhaps because they were issued too late to be relevant, after the economic recovery was well underway. If this interpretation is correct, it affirms that Congress was wise to prioritize speed over precision in dispatching the initial two tranches of PPP loans.”

‘The United States chose to administer emergency aid using a fire hose rather than a fire extinguisher.’

Other pandemic programs had less regressive distributions. Stimulus checks were close to uniform in dollar terms across the four lower income quintiles, while pandemic unemployment insurance benefits went to both the upper and lower tails of the household income distribution. (The highest quintile benefited from the extra unemployment benefits because self-employed business owners were allowed to collect.)

The author said the primary job retention goal of PPP could be better achieved through expanding “work sharing,” or having employers reduce work hours rather than make layoffs. There are 26 U.S. states with work-sharing programs, though they’re not well subscribed, and the authors say these programs should be simplified and automated.

Other higher-income countries responded with a mixture of job retention incentives, including work sharing and wage subsidies. “A key lesson from these cross-national comparisons is that targeted business support systems were feasible and rapidly scalable in other high-income countries because administrative systems for monitoring worker hours and topping up paychecks were already in place, prior to the pandemic. Lacking such systems, the United States chose to administer emergency aid using a fire hose rather than a fire extinguisher, with the predictable consequence that virtually the entire small business sector was doused with money,” the authors said.

In the U.S., the unemployment rate has dropped to 3.9%, from a pandemic peak of 14.9%. The employment-to-population ratio has improved to 59.5% from a pandemic low of 51.3%, but it’s still below the Feb. 2020 level of 61.2%.