This post was originally published on this site

Last year’s lofty average global temperatures, which choked the Western U.S. in drought and fire and kicked up a deadly hurricane in New York, may not have been a record-beater.

But more worrisome for some observers is the lingering temperatures above the 20th Century average for several years now that policy makers and investors should care about, especially those wondering how to improve respiratory health and save shorelines, or tap the technologies that will make solar cheaper and pollution capture scalable.

The cost of dealing with rising temperatures is also soaring. Last year brought the second-highest number of billion-dollar weather and climate disasters on record, a recipe for higher insurance premiums and construction budgets.

Several readings emerge

The average temperature across land and sea surfaces in 2021 was 0.84 degrees Celsius (1.51 degrees Fahrenheit) above the average for the 20th Century, according to a report issued by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Last year marked the 45th straight year that global surface temperatures were above average, according to the report.

Scientists increasingly compare these long-run warmups to temperatures beginning with the 1880s-90s, when the Industrial Revolution took hold.

A separate release from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) said 2021 tied with 2018 for the sixth-warmest year and was hotter than all other years except 2015, 2016, 2017, 2019 and 2020. The years 2020 and 2016 share the temperature record. Last year the U.S. recorded its hottest summer since 1936, and well-above-normal readings came in from unexpected places in the U.S. Pacific Northwest and Canada.

Meanwhile, a report released in early January by the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service ranked 2021 as the fifth-warmest year on record. The nonprofit Berkeley Earth said 2021 tied with 2018 and 2015 as the sixth-warmest year on record in its annual analysis, out this week.

“No one lives at the global average temperature,” said Berkeley Earth Lead Scientist Dr. Robert Rohde. “Most land areas will experience more warming than the global average, and countries must plan their responses to this.”

Steep price to pay

Roughly 8% of the planet’s surface, home to 1.8 billion people, experienced the highest average temperatures ever recorded in those regions, according to the Berkeley Earth report.

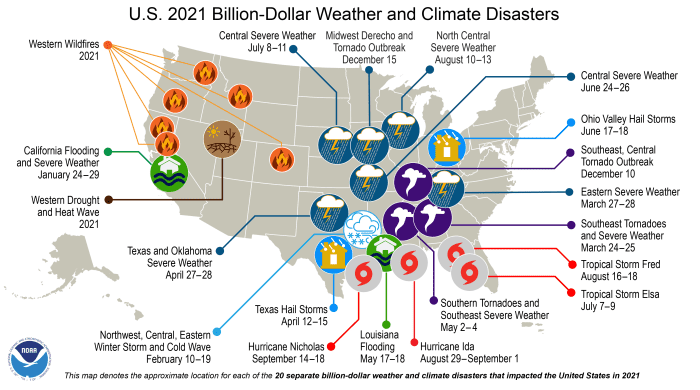

Last year, the U.S. alone experienced 20 separate billion-dollar weather and climate disasters that killed at least 688 people — the most disaster-related fatalities for the contiguous U.S. since 2011 and more than double 2020’s 262, according to NOAA.

Read: Hotter and more frequent heat waves put the work and lives of countless essential workers at risk

The monetary bite from these events totaled approximately $145 billion. This exceeds the total damage of $102 billion from the 22 natural disasters in 2020.

NOAA

Greenhouse gases include carbon dioxide from vehicles, factories and more, as well as the more-potent methane, given off from livestock, landfills and as natural gas is captured. Methane lasts for a shorter time in the atmosphere.

Roughly 190 countries signed a voluntary pact in Paris in 2015 vowing to take steps to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius and ideally to 1.5 degrees Celsius of preindustrial levels. That pact guides updated policies on climate change, including at the U.N.’s latest meeting, in November.

“It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land,” the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded in a report issued in August.

That means “a fix” requires greater human influence, say scientists and cleaner-energy advocates.

‘Cooler’ investing

Many studies have shown that greenhouse gases released into the air by the burning of fossil fuels are the primary driver of climate change and global warming. But weening rich nations, as well as advanced developing nations, off their reliance on convenient, cheaper oil CL00 and gas NG00 is proving to be a drawn-out process.

Some lawmakers favor keeping natural gas in a diverse U.S. energy portfolio alongside wind, solar and nuclear power, even if they back national pledges to hit net-zero emissions in coming decades.

The COVID-19 economic slowdown pared emissions but they’ve come roaring back. Still, the reduction proved to some that behavior modifications and public-private investment in greener technology as the economy rebounds will pay off.

President Biden has committed to a goal to cut the Earth-warming carbon emissions of the U.S. in half by the end of this decade, an ambitious undertaking by most accounts, which requires greater investments in solar, wind, battery storage and hydrogen energy solutions.

Some environmental stocks have taken heat for “greenwashing” or overpromising their climate-change impact, but there’s no doubt the space is only going to expand, including mutual fund and exchange-traded fund opportunities. The assets of self-proclaimed “sustainable” funds tripled between the end of 2018 and mid-2021 to $2.3 trillion, according to Morningstar.

The iShares Global Clean Energy ETF

ICLN,

is among the largest considerations for individual investors with more than $6 billion in assets under management. And the First Trust Nasdaq Clean Edge Green Energy Index Fund

QCLN,

is one entry point to electric-vehicle firms, including Tesla

TSLA,

without limiting a “green play” to just EVs.

Investors might explore specific individual stocks with additional research, such as the maker of photovoltaic-based power systems Sunworks

SUNW,

or residential solar provider Enphase Energy

ENPH,

hydrogen fuel-cell maker Plug Power, or the dividend-paying, long-time renewable energy name Brookfield Renewable Partners

BEP,

Even traditional stocks have a climate-change angle, including General Electric

GE,