This post was originally published on this site

The Federal Reserve’s more aggressive plans outlined on Wednesday to rein in worrying inflation levels aren’t expected to soon drain extreme levels of liquidity from financial markets.

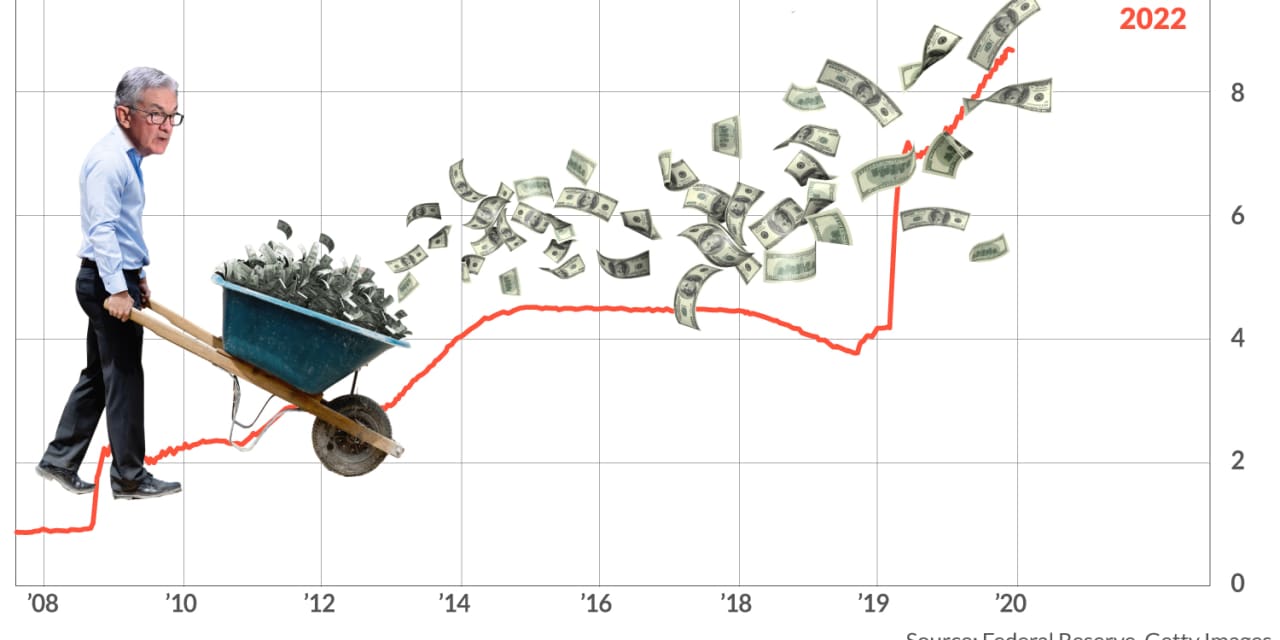

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell now expects to end in roughly three months the central bank’s massive bond-purchasing program, which since 2020 has been a key axel of support for financial markets.

Bond buying, or “quantitative easing,” has been the main contributor to the Fed’s more than twofold balance-sheet increase during the pandemic to a record $8.7 trillion, as of mid-December. It also helped keep credit flowing during the crisis, while driving appetite for U.S. stocks and other risk assets.

But some on Wall Street say the central bank went too far as the economy roared back in the past 21 months, particularly as inflation and asset prices pushed higher, while yields dwindled. Fringe assets, cryptocurrencies like Dogecoin

DOGEUSD,

and meme stocks at the same time gained ardent followers.

The S&P 500 index

SPX,

on Thursday closed less than 1% away from the record high achieved earlier in December, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

endde the day about 1.5% from its November peak.

“Overall, strong economic growth, labor market recovery and elevated inflation clearly have moved the Fed toward an accelerated focus on shifting policy and particularly in getting quantitative easing over with,” BlackRock’s Rick Rieder, chief investment officer of global fixed income, said in emailed comments about the Fed’s pivot.

Commentary: The Fed’s big surprise: All those inflation doves have suddenly become hawks, writes Rex Nutting

BlackRock

BLK,

the world’s biggest asset manager, and other financial heavyweights have for months been calling on the U.S. central bank to end its extreme monetary accommodation, with Rieder suggesting the Fed is “running behind the curve and needs to catch up to rapidly changing events on the ground.”

Still stimulus

Powell on Wednesday laid out cuts of $30 billion to the Fed’s original $120 billion monthly bond-buying program, double the $15 billion reduction announced a month earlier.

At that rate, the Fed’s balance sheet would likely grow beyond its current record $8.7 trillion size, or until the large-scale purchases hit about the two-year mark.

The central bank could then also begin to lift policy rates by 75 basis points next year, under its more aggressive “dot plot” forecast to tackle inflation that’s running at early 1980s levels.

“Notably, no Fed official next year thinks it will be appropriate to keep rates unchanged,” Ellen Gaske, lead economist at PGIM Fixed Income, said in a phone interview. “That really struck me. And it signals they are all on board to pivot and focus on inflation pressures.”

Meanwhile, growing demand for the Fed’s popular overnight reverse repurchase facility hit a record of nearly $1.7 trillion on Thursday, signaling cash sloshing through markets that’s not being used by banks to make loans or others to buy securities, but instead is parked overnight at the central bank.

Also, while the Fed may stop purchasing Treasury

TMUBMUSD10Y,

and mortgage-backed securities

MBB,

in a couple of months, that’s entirely different from selling the cache of assets accumulated during the pandemic.

“It is an issue that is started to crop up with market participants, and a few are expecting the Fed to let some securities roll off the balance sheet next year,” Gaske said, speaking to the decline of the central bank’s bond holdings as it opts out of reinvestment when bonds mature.

“My own view is that while that’s possible as soon as next year, that would not be my base case. I think they will be focused next year on their rate hikes, and I think they will only want to turn one knob of tightening at one time.”