This post was originally published on this site

For decades, everything from sewer systems to schools to stadiums have been built by debt issued by state and local governments. Municipal bonds are a mainstay of the American economy: They level the playing field between tiny towns and massive state economies, letting every issuer reach investors who want a steady stream of income that’s also tax-free.

But what if tax-free bonds stopped being tax-free?

One analyst thinks the market should be more prepared for such a shift. “I don’t see an immediate threat,” said Tom Kozlik, head of municipal research at HilltopSecurities, in an interview with MarketWatch. But in an era where deficit reduction may start to resonate more for lawmakers even as low taxes reign supreme, Kozlik says the muni market needs to be vigilant.

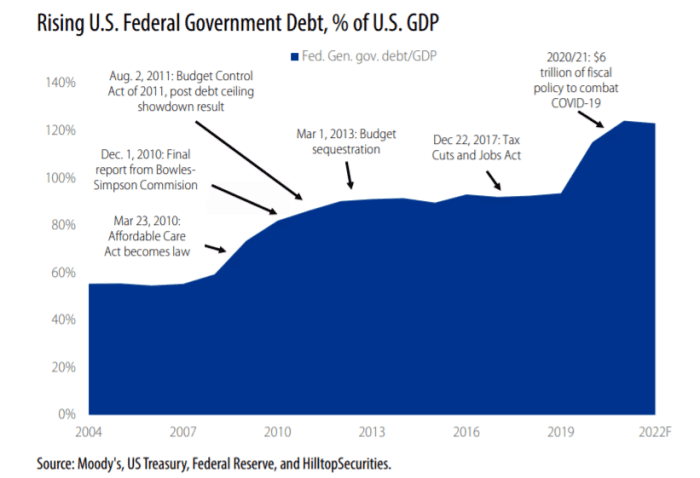

Kozlik believes the threat to the tax exemption started in earnest with the Simpson-Bowles Commission, which was created in 2010 to address the nation’s fiscal sustainability. In its final set of recommendations, the commission suggested doing away with the muni bond tax exemption, which is considered a “tax expenditure” under federal law. That’s when Kozlik started paying attention.

The commission’s recommendations never went anywhere, and the tax exemption lived another day. But, Kozlik points out, the nation’s fiscal challenges, as measured by the ratio of debt to GDP, have only surged since then.

Source: Moody’s, U.S. Treasury, Federal Reserve and HilltopSecurities.

And more tellingly, he notes, Washington lawmakers have since taken steps to curtail the tax exemption, not for the purposes of whittling the national deficit, but simply to make the math work when enacting tax cuts.

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act did away with advance refundings, or the ability for issuers to refinance, which had been a longstanding feature of muni bonds. “That told me lawmakers, any time they want to spend money on something, that tax expenditures like the tax exemption could be and were on the table,” Kozlik said. “That shows that it’s absolutely at risk.”

While muni advocates fought for advance refunding to be restored in the infrastructure bill just passed, those efforts fell short.

Despite that, many muni-market participants don’t tend to agree with Kozlik’s view.

“They always try to chip away, right? That’s the nature of the beast,” said John Mousseau, president and CEO of Cumberland Advisors. “It’s hard to find anything people can agree on these days, but if you’re going to the trouble of having an infrastructure bill be controlled by states and locals, it would be a little disingenuous to start monkeying around with the tax exemption.”

Others point to just how fundamental the tax exemption is not just to the muni bond market, but to communities across the country. The alternative for states and local governments is not to issue taxable bonds, but to not issue at all, Mousseau said — just as the sector endured a decade of austerity following the Great Recession, an outcome Washington lawmakers tried to avoid coming out of the COVID downturn.

George Friedlander, a longtime muni strategist with Citi now running his own consulting firm, agrees. “The muni market as a provider of a federal subsidy is remarkably efficient,” he said.

As a capital market, it distributes access to issuers fairly, including smaller ones that would have a hard time competing in the taxable market. Also, because individual investors are big buyers of individual muni bonds, an issuance of a few million dollars can find buyers more easily than it would from institutional investors, Friedlander told MarketWatch.

It’s important to note that not everyone agrees with that argument. Even muni professionals recognize that from a strict efficiency standpoint, there are better options: States could administer bond banks for their locals, or local governments might tap banks for loans, for example. But in our quintessentially American system, where every jurisdiction wants to be its own sovereign, the muni market seems to strike the right balance.

Still, in another reminder of the muni market’s quirkiness, as fundamental as the tax exemption may be, it remains nearly impossible to put a value on it.

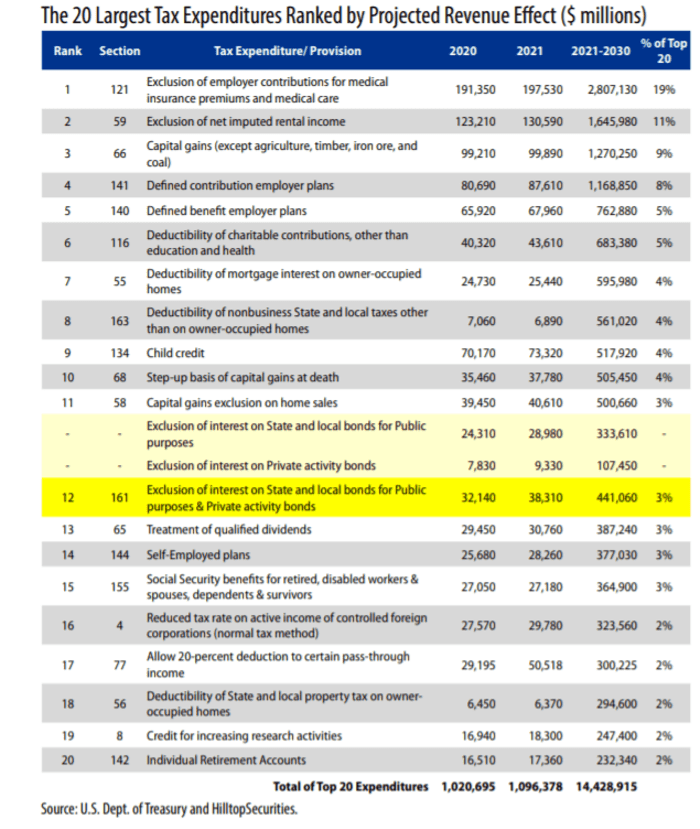

Washington proposals to do away with some or all of the tax exemption tend to focus on the cost of lost taxes: roughly $50-60 billion a year, according to some mid-2010s estimates that may have informed deliberations by Simpson-Bowles and the 2017 tax writers.

A Hilltop Securities analysis of 2021 data from the Treasury Department puts the number at about $38.3 billion annually.

Source: HilltopSecurities and U.S. Department of Treasury

It’s harder to get a sense of how much the exemption helps issuers. In November, Municipal Market Analytics calculated that issuers have paid an additional $8-10 billion in extra interest costs since January 2020 once their ability to do advance refinancings were restricted.

Some analysts, like Friedlander, suggest looking at the spread between yields on bonds issued in the taxable market, like Treasurys, versus munis. The tax exemption allows municipal issuers to pay much lower borrowing costs. On a recent week in November, for example, the average 10-year muni bond was yielding 1.07%, vs. 1.67% for a comparable Treasury note

TMUBMUSD10Y,

per IHS Markit data.

Still, as noted above, since most small issuers wouldn’t be able to compete in a taxable market, that metric may not be the best.

Kozlik says the details aren’t as important as the big-picture trends that will likely inform what impacts the muni market over the coming years. He’s “absolutely” happy to be a Cassandra in the sector, he said. “I’m trying to be forward-thinking. I did it 10 or so years ago and I was right.”