This post was originally published on this site

The Federal Reserve is beginning the first phase of its very gentle, very conditional, very cautious path to stimulus removal. Fed Chair Jerome Powell, just nominated for a second term at the helm of the U.S. central bank, is intent on pushing back against any speculation about thinking about talking about rate hikes.

But around the rest of the world, something quite different is going on in the halls of central monetary authorities from Latin America to Eastern Europe, Africa, and lately even some developed-market countries.

Back in January 2021 I wrote a half-joking, half-serious tweet, remarking that the 300-basis point interest rate hike by the Bank of Mozambique was a “Sign of things to come…”

It was Mozambique’s first interest-rate hike in four years, and came in response to what it described at the time as a “substantial upward revision of its outlook for inflation.”

Fast-forward 10 months. Without really planning it, I decided to add to that tweet — making a live thread tracking the global policy pivot from rate cuts to rate hikes. Since then I’ve noted rate increases both large and small by the central banks of Azerbaijan, Zambia, Brazil, Russia, Iceland, Angola, Sri Lanka, South Korea, Norway, and New Zealand, to name a few. In total, I have counted 94 interest rate hikes across 36 central banks so far this year.

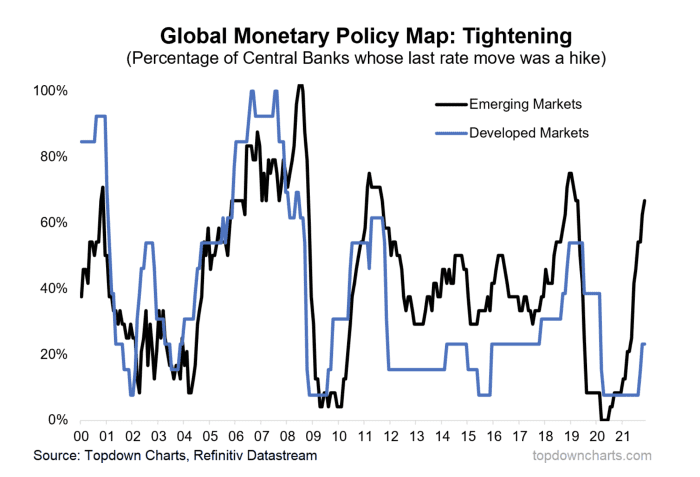

Now obviously if this was just one rate hike by one central bank, or even a handful, it might not even warrant a mention. But when you start talking about these kinds of numbers, it’s hard not to notice a pattern. In that respect, the chart below does a good job of mapping that pattern precisely:

It shows the proportion of central banks in rate-hike mode (defined as the last interest rate move being an increase). After dropping to zero early in 2020, fully two-thirds of emerging market central banks now have pivoted into rate-hike mode.

Why hike now?

There are a few common themes as to why countries around the world are raising rates, including inflation, currency and financial stability. Let’s take a closer look:

Inflation: We quickly went from few people talking about inflation at the start of the year to inflation being perhaps the hot macro topic of the past few months.

Base effects (easier to record a higher pace of growth when comparing to a low base), bounce backs (reopening + stimulus = strong demand), and backlogs (supply-chain hell) combined to drive a sharp shift in both inflation and inflation expectations.

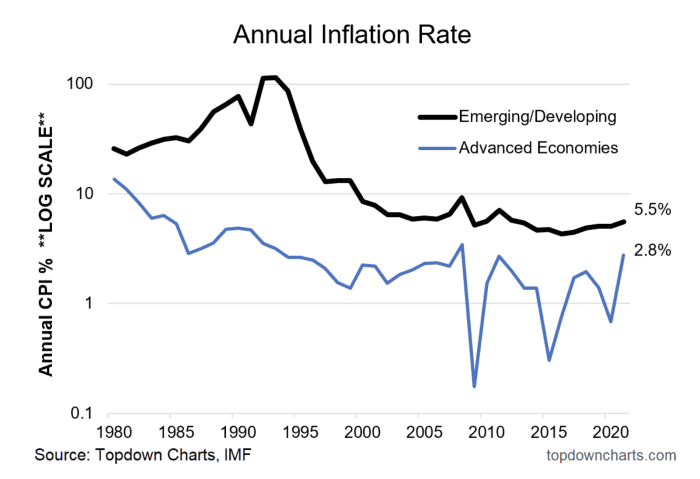

Emerging economies are particularly sensitive to inflation. In recent times, as a group, they’ve tended to see an annual rate of inflation twice that which you would see in developed economies. Moreover, you only need to go back just over 20 years to see hyperinflation in emerging economies (as a group they saw peak inflation of 115% in 1993, and double-digit inflation all the way through to 2000).

Think about your average emerging market central bank governor — many of them were probably junior economists 20 years ago. Their formative years were no doubt heavily influenced by runaway inflation. Little wonder then they are hot on the trigger to hike rates as inflation heats up.

Currency: Many central banks have also lifted rates in effort to prop their currencies up as the U.S. dollar

DXY,

strengthens. The line of reasoning here is two-fold: higher inflation (all else equal) means a fundamentally weaker currency, and higher interest rates appeal to carry traders looking to bank the higher yields: bringing flows and lifting demand for a country’s currency.

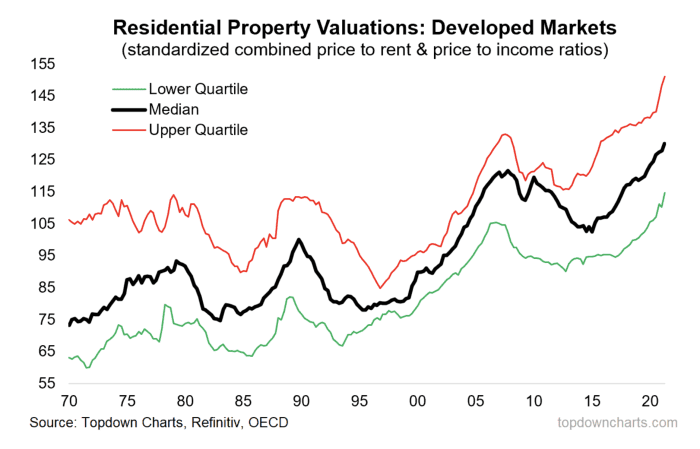

Financial stability: This term is basically a euphemism for “try not to blow up bubbles.” In other words, if you keep rates too low for too long you risk igniting asset-price bubbles, which if they burst in a chaotic fashion can trigger financial instability. Case in point: the housing bubble of the mid-2000s, its subsequent bursting and the ensuing Great Financial Crisis.

On that note, we probably should pay more attention to this aspect, as developed-economy housing market valuations have already sailed past the pre-financial crisis highs.

Yes that’s right: Ultra-low borrowing costs have helped push housing market valuations in some countries well above pre-financial crisis levels. This is one reason why it’s said that monetary policy is a blunt tool — it roughly does the job when it comes to avoiding deeper economic recessions and depressions, but the price is often higher asset prices.

“Expect less of a tailwind for risk assets, upward pressure on borrowing costs, and likely more volatile markets going forward.”

Market impact

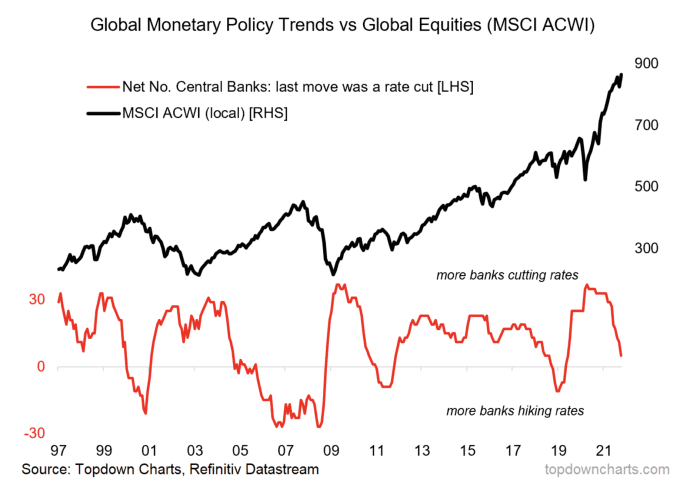

The global policy pivot to rate hikes (likely to be soon joined by Canada and the U.K.) means investors can expect incrementally less of a tailwind for risk assets, upward pressure on borrowing costs, and likely more volatile markets going forward.

Indeed, mapping out the previous paths in policy, the chart below shows how shifts from easing to tightening at best means a leveling-out or regime shift in the market; e.g. from a near vertical line to more chopping and ranging. At worst, if tight enough for long enough, this policy change can trigger an outright shift from bull market to bear market.

You might be thinking, what do all these random small, emerging-market central banks hiking interest rates have to do with the S&P500

SPX,

? You’ve probably heard the saying that when the Fed sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold, but in this sense, given the Fed is still likely to be dragging its feet on policy for some time, it’s almost more that the rest of the world catches a cold and U.S. equities sneeze.

You only need to go back to 2015-16 where much of the volatility in U.S. markets back then was driven or triggered by issues in China and emerging markets, or in the post-financial crisis period when the eurozone debt crisis was raging and weighing on global investor sentiment.

Beyond regional crises — which can be precipitated by premature stimulus removal — the bigger issue is the common themes motivating monetary policy.

While each central bank has its own set of circumstances, the common theme is a reaction to higher inflation, stronger growth and a desire to avoid overcooking markets. It’s the smaller/developing-country central banks that are most exposed to these global trends, and so we can look at them as bellwethers or leading indicators.

The forces in motion that triggered a rate hike in Mozambique are the same forces that will ultimately drive the Fed to step away from stimulus.

It may take time, but one thing I know to be true is that these things go in cycles. While it looks and feels like the Fed has your back forever in the markets right now, this won’t be always true. “Don’t fight the Fed” means swim with the tide, not against it, and the tides here are clearly turning.

Callum Thomas is founder and head of research at Topdown Charts, a global asset allocation and economics research firm.

More: What a Fed led by Powell and Brainard means for Americans’ bank accounts

Plus: Why it matters to you that Jerome Powell will serve another term as chair of the Federal Reserve