This post was originally published on this site

For years, many have held out hope that the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield will head back toward 2%, the psychologically key level seen as representing a healthy U.S. economy.

It hasn’t happened yet. And while the consensus forecast is now calling for that to occur in 2022, a smaller number of analysts are warning of the opposite: that the widely followed yield will generally continue to drift lower, as it has for each of the past three or four decades.

The influential 10-year yield

TMUBMUSD10Y,

which impacts everything from auto loans to mortgages, credit cards and student borrowing, hasn’t been at 2% since August 2019. It’s repeatedly come up short of that level, even when the U.S. was at the tail end of its longest economic expansion on record, and the yield now hovers around 1.60% despite the highest inflation in almost 31 years. And investors see few, if any, meaningful catalysts left to drive it sustainably higher by year-end.

Dimitri Delis of Piper Sandler Cos.

PIPR,

in Chicago and Richard McGuire of Rabobank , a Dutch conglomerate, are among the small group of analysts who have dared to stay in the lower-for-longer camp on yields. They say they have nervously wondered from time to time if they should go out on such a limb, but have nonetheless stuck to their views by focusing on decades-long trends and a big-picture take on what is driving continued demand for U.S. government bonds.

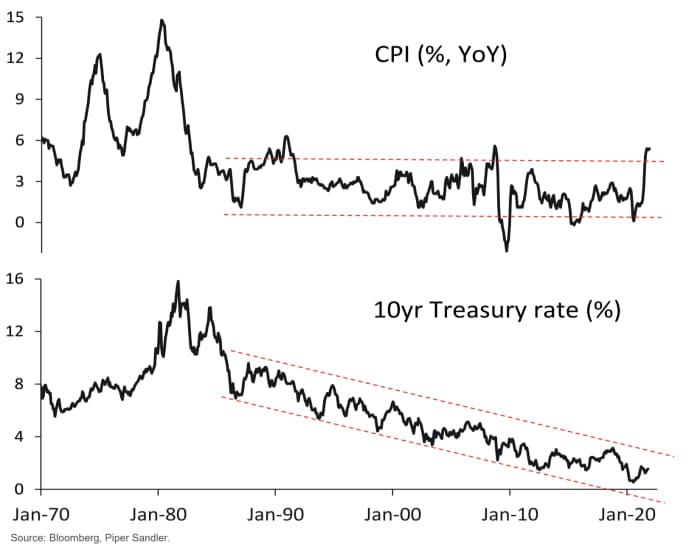

“I just follow the data and won’t deviate from it no matter how wrong or right it looks,” said Delis, a trained nuclear physicist who is a senior econometric and macro strategist for Piper Sandler. He says that fifty year’s worth of data on the 10-year yield shows that it moves lower with each passing decade, while fluctuating within a roughly 70 basis point range annually in either direction, despite occasional catalysts that temporarily push it up.

Bloomberg, Piper Sandler

“Every time there is a catalyst for yields to go higher, the catalyst fades,” Delis said via phone. “Why? Because yields naturally want to go lower.” Still, he says, “sometimes I look at the consensus and think, `I don’t want to be the only one stuck out there.’ ”

Delis and Rabobank’s McGuire say the factors driving the 10-year yield lower include continued demand from foreign buyers and U.S. corporations, a dearth of positive-yielding options from other countries, and the likelihood that today’s hot U.S. inflation will give way to weaker economic growth and disinflationary trends once all the dust settles. In McGuire’s view, much of the Fed’s pandemic-driven stimulus is being funneled into financial assets like bonds instead of the economy, contributing to the drop in yields.

Aging demographics, globalization and automation are just some of the disinflationary forces that were already in place before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and they haven’t gone away, Delis and McGuire said. Their forecasts for 2022 include the possibility that the 10-year rate could fall to 1%, a level last seen in January before the U.S. economy fully reopened. The strategists also see a substantial risk that the yield drifts toward zero over time, considering other developed bond markets are already there — a view articulated in 2019 by Jan Loeys of JPMorgan Chase & Co.

JPM,

Longer-dated yields like those on the 10-year

TMUBMUSD10Y,

and 30-year

TMUBMUSD30Y,

are typically regarded as a sign of investor sentiment on the economic outlook, though some say their signaling powers have been distorted by the Fed’s pandemic-era bond-buying program.

When yields are falling, investors are said to be buying Treasuries, presumably for their safe-haven appeal, and the economic outlook is seen as negative. And vice versa: when yields are rising, investors are seen selling off government bonds amid greater confidence and presumably turning to riskier assets, like stocks. Recently, though, stocks and bonds occasionally have moved in conjunction with each other, with investors either pouring into both asset classes or pulling out of them at the same time, because financial markets are believed to have become increasingly divorced from economic fundamentals.

For years, bigger financial market names like billionaire bond investor Bill Gross have overshadowed the voices of the contrarian few in the lower-for-longer camp. Gross has repeatedly said that he thinks the bull market in bonds is over, meaning an end to the rampant buying of Treasuries that drove yields lower for decades. Bank of America’s Michael Hartnett and economist Jeremy Siegel are among those who have expressed a similar view since last year.

Meanwhile, bond-market bulls like Delis, McGuire and HSBC’s Steven Major, the Hong Kong-based global head of fixed income research, have generally been right about the downward drift in Treasury yields, though off the mark about precise levels. Late last year, Major’s team reportedly called for a continued rally in Treasuries in 2021 and saw the 10-year yield staying in the 0.75% range for a few years. More recently, he said that the 10-year Treasury yield needs an “uber-hawkish” shift by the Fed in order to get back to 2%.

The lower-for-longer camp’s views are especially noteworthy now because the Federal Reserve is in the process of pulling back on its extraordinary support of the economy and is widely expected to start raising its policy interest rates next year to combat higher inflation. The tapering of its bond purchases and the prospect of rate hikes are generally seen as catalysts that should be driving yields up.

While rates on shorter-dated debt have jolted higher since September in anticipation of a policy tightening by the Fed, long-dated yields haven’t moved by nearly as much, catching even the most sophisticated investors off guard. Some hedge funds have reportedly suffered substantial losses from wrong-way bets on the direction of rates this year after positioning for the differential in yields to widen, instead of narrowing.

Delis and McGuire say they’ve turned out to be wrong, too, when it comes to picturing the impact that U.S. political outcomes might have on the bond market.

For instance, Delis says he did not think Donald Trump could be a catalyst for interest rates rates to move higher, but after Trump’s surprising 2016 presidential-election win over Hillary Rodham Clinton, the 10-year Treasury yield jumped by the most in three years.

Last December, Delis expected the 10-year yield to possibly average 1.1% for the year and fluctuate between 0.5% and 1.7%, but only the latter has come true.

Meanwhile, also at the end of last year, McGuire says he expected the 10-year to languish around 1% by the end of 2021. That was before Democrats took control of the U.S. Senate in January, leading to a substantial spike in yields over the following months.

“The more the market moves away from your forecast, the greater the risk you’ve completely misinterpreted something,” said McGuire, Rabobank’s head of rates strategy and a graduate of the University of Oxford’s Merton College. “That leads to a lot of soul searching, but as ever, we’re very loathe to jump on a bandwagon unless we can substantiate why we’ve done so.”

Before becoming a strategist, McGuire ran a language school in Slovakia during the early 1990’s, after the fall of the Berlin Wall. He says he watched as a post-socialist economy was rebuilt into a capitalistic one, an experience that gave him “a world view based not on textbook descriptions.”

“What’s happening now is many people are refusing to abandon textbook approaches, and we think structural forces have only strengthened during the pandemic,” McGuire said via phone from London.

Earlier this year, it seemed that President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan would be enough to jumpstart the economy and possibly send the 10-year toward 2%, from a year-to-date low of 0.9% on Jan. 4, but the yield has not climbed above its March level of almost 1.8% all year.

Meanwhile, forecasters kept revising their expectations higher throughout the first half, winding up in June with a consensus estimate for the 10-year yield to end 2021 at 1.9%. Instead, the rate fell to as low as 1.1% in August and has largely stayed in a narrow range below 1.63% for months, despite hot inflation readings and the Fed’s Nov. 3 decision to gradually pull back on monetary stimulus.

Theoretically, it’s still possible for the 10-year rate to jump 40 basis points to 2% in six weeks’ time before the year ends, since a similar-sized magnitude jump was seen from February to March, but the Federal Reserve has only one policy meeting left, in December, and is beginning to taper bond purchases.

Meanwhile, two more potential catalysts — persistent U.S. inflation and sooner-than-expected Fed interest rate hikes next year— are already being factored in by traders. A final catalyst, the imminent announcement of President Joe Biden’s pick to be Federal Reserve chair, has been talked about in markets for weeks.

The coronavirus pandemic has created distortions and supply-side shocks, which make it harder for traders and analysts to interpret data. Unlike many traders and analysts focused on signs of persistent inflation, McGuire sees evidence that the pandemic “has weakened labor’s bargaining power,” as reflected by lagging wage growth in areas like transportation and warehousing.

“And if wages don’t respond enough to price pressures, consumers will feel poorer,” McGuire said. “So what’s inflationary now is disinflationary later and, if we look around corner, all of positives in inflation this year could reverse.”

Before becoming a strategist, McGuire ran a language school in Slovakia during the early 1990’s, after the fall of the Berlin Wall. He says he watched as a post-socialist economy was rebuilt into a capitalistic one, an experience that gave him “a world view based not on textbook descriptions.”