This post was originally published on this site

Conventional wisdom says that inflation is bad for the stock market. Yet the U.S. stock market this year has remained strong in the face of unexpectedly high inflation.

Since mid-May, when it was first reported that the CPI’s 12-month rate of change had spiked, the S&P 500

SPX,

has gained more than 15% and the tech-heavy Nasdaq 100 index

NDX,

is up almost 23%.

Does that mean the stock market is living on borrowed time, and will soon succumb to the gravitational pull exerted by higher inflation? Or is the conventional wisdom on this subject just wrong?

Now is a good time to investigate these questions, since the U.S. government reported this week that the CPI over the latest 12 months has risen at its fastest rate in over 30 years.

My analysis of the historical record reveals that the relationship between equities and inflation is far more complex than it initially appears. That’s because there are both plusses and minuses to inflation’s impact, and it’s difficult to predict the net impact of inflation’s various consequences.

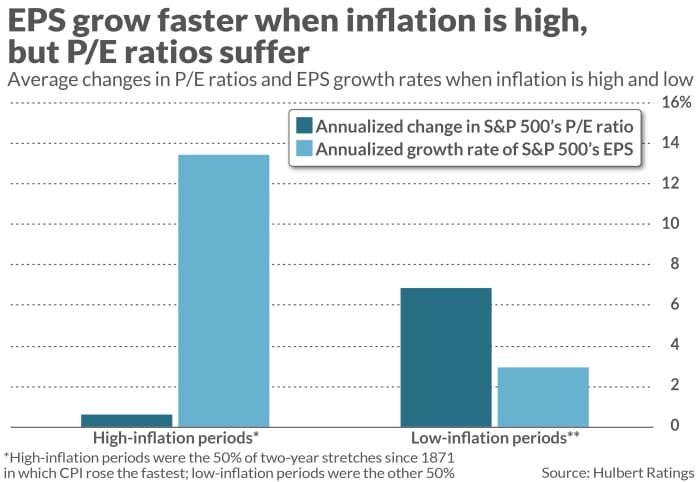

Consider first inflation’s impact on earnings: Because companies often are able to charge higher prices when inflation heats up — they have “pricing power,” in other words — their earnings do not suffer as much as you might think. In fact, according to data back to 1871 provided by Yale University’s Robert Shiller, the S&P 500’s nominal earnings per share have grown faster, on average, when inflation has been higher.

This tendency is why the stock market is a good inflation hedge. Yet investors all too often overlook this valuable tendency, since they focus on nominal earnings growth rates rather than real growth rates. They extrapolate the slower nominal earnings growth rate of a low-inflation period even when inflation heats up. Economists often refer to this mistake as “money illusion” or “inflation illusion.”

Corporate earnings’ ability to hedge inflation is the good news. The bad news is that inflation causes P/E ratios to decline, since inflation reduces the discounted value of future years’ earnings.

These two distinct impacts are summarized in the chart below. To construct the chart, I segregated the period since 1871 into two subsets according to the CPI’s trailing 2-year rate of change. Notice that the EPS growth rate has tended to be higher when inflation is higher, but the P/E ratio has tended to be lower.

What to watch for — and watch out for

How do these countervailing factors interact in practice? The answer depends on whether you focus on the near-term or the long-term. Over the near-term — up to a year, or so — inflation historically has been a net negative for stocks. That’s because inflation’s negative impact on the P/E ratio is immediate, while its positive impact on earnings doesn’t kick in for a couple of years. Once your time horizon extends two or three years, these effects on average cancel each other out.

The investment implication: If inflation proves to be more than transitory and the stock market declines significantly, you might want to treat the selloff as a buying opportunity.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: Why the hottest inflation in 3 decades isn’t rattling stock-market bulls

Plus: IRS releases new standard deductions and tax brackets as inflation soars