This post was originally published on this site

Fans and shareholders of Tesla are making stronger and louder arguments about the future of their favorite company. In them, they draw analogies to one of the most successful brands and businesses in the history of capitalism. They suggest that automaking may go the way of handset manufacturing and that – for Tesla

TSLA,

– there is a strong resemblance to the Apple

AAPL,

vs. Nokia/Blackberry/Ericsson/Motorola dynamic.

For those that don’t know, in the early 2000s it was unimaginable that these legacy mobile phone manufacturers could disappear. In 2006, Research in Motion (RIM), the company making BlackBerrys, lost a patent suit against NTP and a U.S. District Court judge slapped an injunction on sales. The Defense Department stepped in, claiming that a Blackberry injunction was a threat to national security. Meanwhile, industry leader Nokia held a 40% market share and by the end of 2007 sported a $230 billion market cap.

But something else happened in 2007.

Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone.

And that changed the game for Nokia, Blackberry and the entire industry, forever.

Coincidentally, Jobs introduced that iPhone seven months after Tesla introduced the Roadster at the San Francisco International Auto Show. Fast forward to 2021, and the bulls are suggesting that Apple’s overwhelming success in handset manufacturing can be mirrored in automobile manufacturing by Elon Musk’s Tesla.

For this to happen, let’s first assume that within 15 years buyers will demand a broadly similar “form factor” for any vehicle. Today, there are 250 brands of cars sold to fit all appetites and budgets, and perhaps over 1,000 trims. Meanwhile, thanks to the iPhone, handset hardware has gone from a myriad of styles, sizes and forms to basically one.

Similarly, let’s imagine that the production and value of automobiles and light trucks will become less about the style or performance that is demanded and instead mostly about the software inside the vehicle.

Finally (and this is a huge debate, but) let’s presuppose that Tesla will have better software – most importantly better autonomous driving capability – than any other vendor or manufacturer, whether in Silicon Valley, Detroit, Wolfsburg or elsewhere.

In other words, let’s assume that Tesla is going to become the Apple of automakers.

To do this, we need to ignore that Apple is not just a handset manufacturer. In the first three quarters this year, it reported over $150 billion of iPhone sales, which represented 55% of total sales. It also reported sales from the “Services” segment, which included sales from advertising, digital content, AppleCare and other lines. If we assume all that revenue was driven by the iPhone (even though not all was), then we get the iPhone representing about 65%-70% of Apple’s sales.

This implies Apple has a substantial business (about $110 billion this year) selling Macs, iPads, wearables and accessories too. So in our “Tesla is Apple” analogy, we need to assume that Tesla will make similar extensions into new products.

We also need to ignore that most of the profit for Apple in handsets comes from mobile advertising and app sales, much of which Apple reports in that services segment noted above. Again, to stay in our framework, we also need to believe that Tesla would generate something similar via its over-the-air updates or its own app store.

Making all these assumptions, then future margins in “automaking” – for at least one manufacturer – could theoretically start trending up toward the margins generated today by Apple.

So in terms of handset market share, people around the world are going to buy approximately 1.4 billion handsets this year, and the average selling price will be about $320. Apple has about 16% of the global market, and will sell about 225 million iPhones.

Just guessing here, but if these iPhones are sold at an average price of $890, then the average price of all the other phones sold in the world needs to be about $125 for the math to make sense. And because Apple can sell its iPhone at such a huge premium and produce remarkable revenues from advertising and app store sales, it generates a whopping 24% earnings margin.

In comparison, Volkswagen

VOW3,

VWAPY,

which started operations in 1938, has worked its way up to a global market share of 12.0% and generates net income margins of 5.0%.

Toyota

7203,

TM,

which also started operations in 1938, also has a global market share of 12.0% and generates even better net income margins of approximately 7.0%.

Nokia, for what it is worth, generated 14% net margins before the iPhone changed the game. In other words, even before Apple showed up, handset manufacturing was over twice as profitable for market leaders as making cars.

Anyway, folks around the world will buy about 75 million new cars this year, and at an average price of $30,000 (ballpark) this works out to over $2.2 trillion in sales. This is about five times larger than the handset market, which will come in at about $450 million. Toyota and Volkswagen are the largest – and best in class – scale automobile manufacturers in the world. Other groups, including Ford

F,

Stellantis (FCA/Peugeot)

STLA,

Daimler

DAI,

General Motors

GM,

Honda

7267,

HMC,

BMW

BMW,

and many others also have significant share.

This year, Tesla will sell about a million cars, representing a global market share of 1.3%.

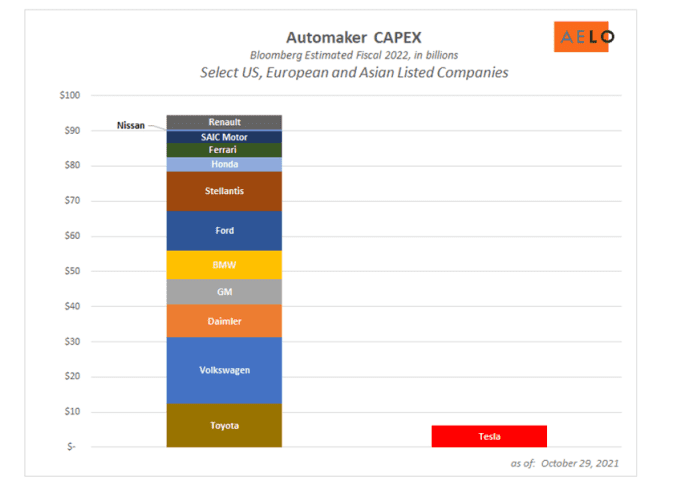

And dare I say that each of Tesla’s competitors will be loath to surrender more market share, thus the huge amount of R&D and capital spending they will devote to the upcoming transition to electric vehicles (EVs). On the CAPEX metric alone, we can see that these competitors will actually spend more next year than Tesla.

A lot more.

Uncredited

But still, let’s assume all the legacy automakers fail to maintain share. Let’s also envision that most of the profits in the industry will eventually go to Tesla (as they have in handsets to Apple).

As a baseline, analysts anticipate that Tesla will generate over $50 billion in sales this year. Over 85% of these sales are related to its automotive business.

In 2035, if EVs represents 95% of all new cars sold, and Tesla has the same 16% market share as Apple does today (significantly eclipsing that of VW or Toyota), it will be producing 22 million cars and light trucks, and generating sales of over $1 trillion.

This year, analysts anticipate that Tesla will generate over $10 billion in net income (which will include approximately $1.2 billion in profits driven by regulatory credits.

If Tesla were able to generate the same 24% net earnings margin as Apple does today (remember VW is at 5% and Toyota at 7%), then it would produce about $250 billion of earnings in 2035.

As Tesla has grown from zero to one million cars, it has built production facilities in Freemont, Shanghai and soon Austin; battery-producing gigafactories in Nevada, Buffalo, Germany and Austin again; and other manufacturing and tooling facilities in Michigan, Ontario, Shanghai, two more in California and three more in Germany.

To finance this expansion, Tesla went from 35 million diluted shares in 2009 to 641 million in 2015 to over 1.1 billion today. Of course some of these went to key executives in the firm as compensation, but for the most part, this share issuance helped to finance the firm’s stunning growth to date.

And if Tesla is going to build over 20 million units a year (up from about 1 million this year), this will require a lot more capital. But given its strong share price and internal cash flow generation, let’s assume that the rate of new share issuance at Tesla will slow dramatically, to just 1.5% new shares per year. At this rate, they would have “only” 1.4 billion shares in 2035.

And in that year, on production of 22 million vehicles at an average selling price of $46,000 (again, our guess) and doing 24% net earnings margins, this $250 billion of earnings would work out to about $178 per share.

Given Tesla’s domination in this scenario where it maxes out its market share, the only negative is that it would no longer be a secular story, but one more exposed to the cyclical nature of automaking. So its huge amount of revenue and income would naturally be growing much more slowly by then. But, again for the sake of this exercise, let’s assume that Tesla will still find a way to continue to generate a consistent 10% EPS growth on that $250 billion number.

And despite this slowing, let’s also assume that investors will want to pay a P/E ratio of over 20 for a now huge and cyclical business.

On a P/E of 22.5, that would work out to a market cap of $5.6 trillion, and a share price of $4,000.

These are big numbers. And despite what we hear from the more optimistic of the Tesla bulls, let’s also assume that today’s shareholders only hope to make 10% per year between now and 2035.

If we discount that $4,000 by 10% back to today, the shares are worth $1,050.

That is pretty close to where we are right now.

So all that above is what needs to happen for $1,050 to be a fair share price today.

Doubters, admittedly like us, will suggest that the execution risk is tremendous, and these market shares (and particularly the margins) may be impossible.

Yet, despite the fact that we actually can’t ignore the differences between the mobile phone and automobile industries noted above, the believers – who may indeed be right – will literally need to see Apple-esque industry dynamics, market shares and earnings margins for this all to make sense.

It is also important to consider that for there to be even more upside in the shares from current levels, Tesla will actually have to exceed everything that Apple has accomplished.

Whether a bull or a bear, there is no doubting that what Musk has achieved thus far has been nothing short of incredible. Five years ago, few would have thought it even possible that Hertz would order 100,000 Teslas in a single order for its car rental fleet, or that Tesla would produce and sell a million cars in a single year.

He will continue to do incredible things. He has changed the world and the mindset of his competitors. None of that is in question. The future that his share price is discounting is the question we are asking today.

Andrew Dickson is the chief investment officer of Albert Bridge Capital, a manager of concentrated equity portfolios for institutional investors. He holds holds no position in Tesla, long or short. Follow him on Twitter @albertbridgecap.