This post was originally published on this site

Natalee Allen didn’t rush to stock up on toilet paper, paper towels, shelf-stable foods or any other products that were in short supply at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

“I was actually kind of annoyed at people who did panic buy back when COVID started because I couldn’t find anything on the shelves that was nonperishable,” Allen, 24, who lives in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, said.

Now, more than a year-and-a-half into the pandemic, she herself has become one of these agitated consumers.

Her six-week-old daughter has exclusively eaten Sam’s Club

WMT,

generic baby formula, and Allen is worried her baby might not like any other brand.

“‘You’re depending on this supply chain and other people to feed your baby instead of yourself.’”

Even though Allen, a speech pathologist currently on maternity leave, didn’t hear or read anything about supply chain disruptions affecting Sam’s Club’s baby formula inventory, she doesn’t want to take any chances.

When she and her husband, an airline customer service representative, get their next paychecks, they’re planning to buy “a couple hundred dollars worth of baby formula” to get them through the next couple of months.

It’s anxiety-inducing for Allen to have to depend “on this supply chain and other people to feed your baby instead of yourself,” she said, adding that breastfeeding didn’t work out with her daughter.

Natalee Allen, pictured, is planning to buy hundreds of dollars worth of baby formula from Sam’s Club to ensure that she’ll have enough for her six-week-old daughter in case supply chain disruptions cause shortages.

Photo courtesy of Natalee Allen

(Sam’s Club didn’t respond to MarketWatch’s request for comment regarding the extent to which their baby formula inventory is especially vulnerable to supply chain disruptions.)

Allen isn’t the only one who’s changed her shopping habits recently. Concerns about shortages stemming from supply-chain disruptions — a product of global labor shortages and factory shutdowns — appear to be leading other Americans to hoard goods again, in a repeat of behavior last seen at the start of the pandemic.

Earlier this month, Port of Los Angeles said it was moving to 24/7 operations, and dockworkers are ready to work more shifts as part of an initiative that President Joe Biden and White House officials hope will ease supply-chain snarls.

“We are in an unprecedented challenge in regards to the supply chain,” Tom Cove, CEO of the Sports & Fitness Industry Association, told MarketWatch last month.

For the most part, it’s not a widespread phenomenon — at least for now. But there are some signs that there could be another run on some household items.

The total on-shelf-availability rate in supermarkets was 94.6% in September, a decrease from 95.2% in August, according to data from NielsenIQ.

That means that retailers generated 94.6% of the revenue they expected to last month — a sign that stores aren’t able to stock empty shelves to meet consumer demand.

Helen Evans, pictured, spent $500 over the past two months stockpiling frozen and canned vegetables.

Photo courtesy of Helen Evans

Still, if you’re increasingly noticing empty shelves in some aisles at your grocery store, you’re not alone.

Around two months ago, Helen Evans, 51, noticed the freezer aisle was empty at her local H-E-B supermarket in Houston, Texas. The supermarket chain, based in Texas and Mexico, didn’t respond to MarketWatch’s inquiry regarding whether supply chain disruptions were the cause of the shortages.

“‘Any given day, you’re going to have something missing in our stores, and it’s across categories’”

“No one was saying anything but their facial expressions were saying it all,” Evans, who owns a small business that leases party equipment, told MarketWatch. “I was concerned about what I was seeing.”

She did more research and learned that bottlenecks at Chinese ports could be the source of the shortages. That prompted her to stockpile water, noodles, frozen and canned vegetables as well as toilet paper for the past two months.

Recently she had to stop stockpiling goods, which cost her around $500, because she has no more room in her freezer or pantry, she said.

“I could be overdoing it, but you never know,” Evans said adding that she’s now prepared in the event that Houston experiences power outages from severe storms, like it did earlier this year.

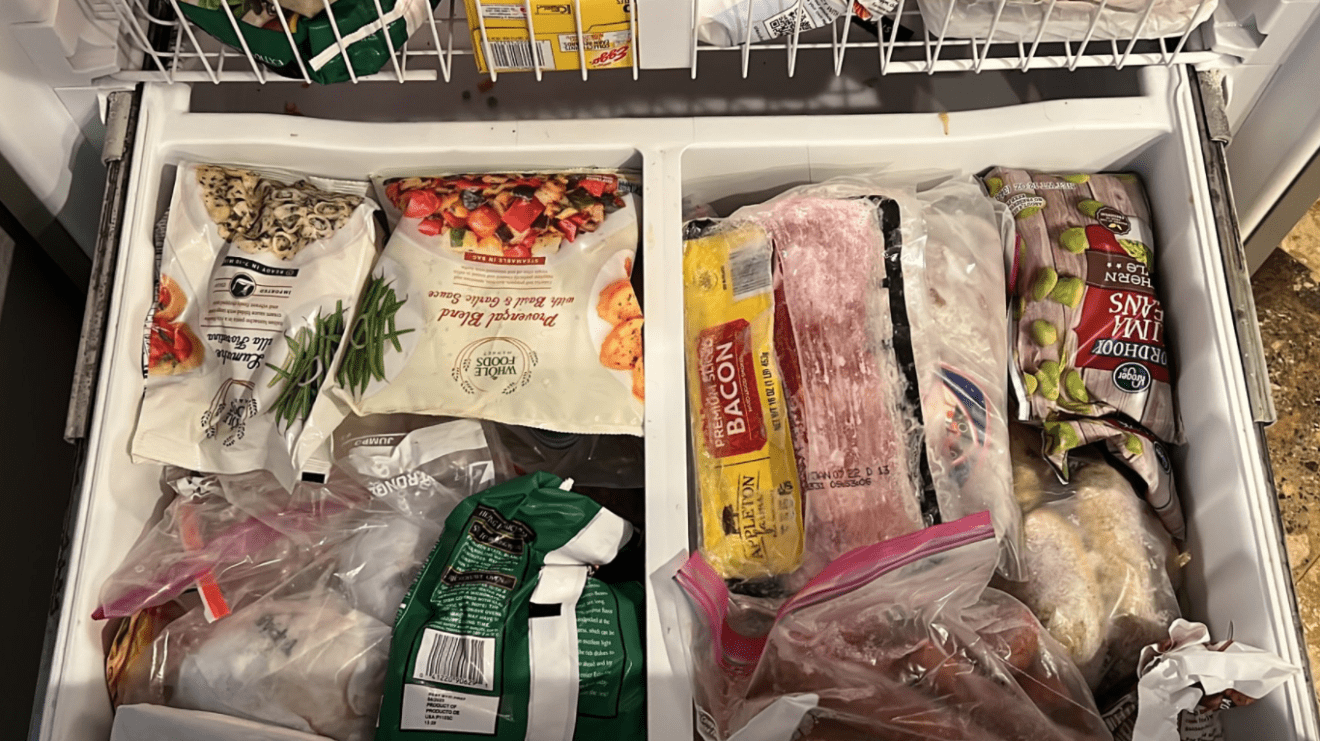

Helen Evan’s freezer is filled to the brim with goods she’s been stockpiling for around two months over fears that supply chain disruptions could cause a run on food.

Photo courtesy of Helen Evans

People are looking for signs of supply-chain disruption, and it’s making them nervous. Vivek Sankaran, CEO of the grocery chain Albertsons

ACI,

recently told Bloomberg, “Any given day, you’re going to have something missing in our stores, and it’s across categories.”

“It is sensible to make sure that we are well-provisioned, especially as news of the supply chain remains far from positive,” said Marcia Mogelonsky, director of insight within the food and beverage division at Mintel, a market research firm.

“The advantage of stockpiling and managing our own food supplies is that we won’t get caught short,” she said.

“‘It is sensible to make sure that we are well-provisioned, especially as news of the supply chain remains far from positive.’”

“If things improve, then we will just balance our at-hope overages by ‘eating down’ our supplies,” she added.

It’s important to remember that not every American has the luxury of buying more food than they need at a given time. In fact, nearly 20 million American families reported that they sometimes or often didn’t have enough food to eat from Sept. 29 to Oct.11 in the Household Pulse Survey published by the U.S. Census Bureau.

“I feel really grateful that I’m in a position that I can stock up,” Allen told MarketWatch. “Part of me wonders if there’s like a moral or ethical dilemma in stocking up when there are other people who can’t.”

MarketWatch wants to hear from you! How are supply chain disruptions impacting your day-to-day lives? Email elisabeth.buchwald@marketwatch.com to share your experience.