This post was originally published on this site

CHAPEL HILL, N.C.—Here’s another entry for “Ripley’s Believe It Or Not”: Higher interest rates don’t have to make your bond mutual fund suffer.

This goes contrary to everything you’ve been told about how bond prices move inversely with interest rates. The conventional wisdom about bonds and interest rates is why so many investors today are avoiding bonds and bond funds, convinced that interest rates are headed higher in coming years.

That isn’t necessarily a reason to avoid bonds

TMUBMUSD10Y,

however. That’s because they also play a valuable role in reducing the risk of your stock portfolio, which is something for which you should be willing to forfeit at least some return. Just as you don’t object to paying an insurance premium to protect your house against fire, even if your house never burns down, you shouldn’t automatically avoid bonds just because they don’t always make money.

But there is an even more fundamental reason why the conventional wisdom about bonds and interest rates is misleading. While higher interest rates undeniably will cause bond prices to fall, your long-term total return will be unaffected by those higher rates, assuming your bond portfolio is structured so as to maintain a more or less constant average duration.

Bond duration and bond ladders

To appreciate this unexpectedly good news, it’s necessary to review a few things about how most bond mutual funds are constructed. Almost all are designed to maintain their average duration, which is their sensitivity to changes in interest rates. As a general rule, bonds with longer maturities will have longer durations.

To illustrate, contrast the Vanguard Intermediate Term Treasury ETF

VGIT,

with Vanguard’s Long-Term Treasury ETF

VGLT,

The former has an average duration of 5.4 years, according to Vanguard, while the latter sports an average duration of 18.1 years.

To maintain their average duration, bond funds employ what’s known as a bond ladder. With a ladder, the proceeds of any bond that matures are reinvested in another bond with a sufficiently long maturity and duration so that the ladder’s average remains more or less unchanged.

Notice what this means for how a bond ladder responds when interest rates rise. Though the prices of previously-held bonds will decline, new bonds will constantly be added to the portfolio with higher yields. It turns out that over time, those higher yields make up for those price declines.

How long must you hold for this happy result to occur? One year less than twice the bond ladder’s average duration. That’s according to a formula derived by Martin Leibowitz and Anthony Bova, managing director and executive director at Morgan Stanley, respectively, and Stanley Kogelman, a principal at New York-based investment-advisory firm Advanced Portfolio Management. They presented it in an article published in 2015 in the Financial Analysts Journal, entitled “Bond Ladders and Rolling Yield Convergence.”

The formula in practice

To illustrate the remarkable accuracy of their formula, I will focus on bond ladders containing intermediate-term corporate bonds with an average duration of about five years. According to the formula, your total return will be immune to interest-rate changes provided you hold for at least nine years.

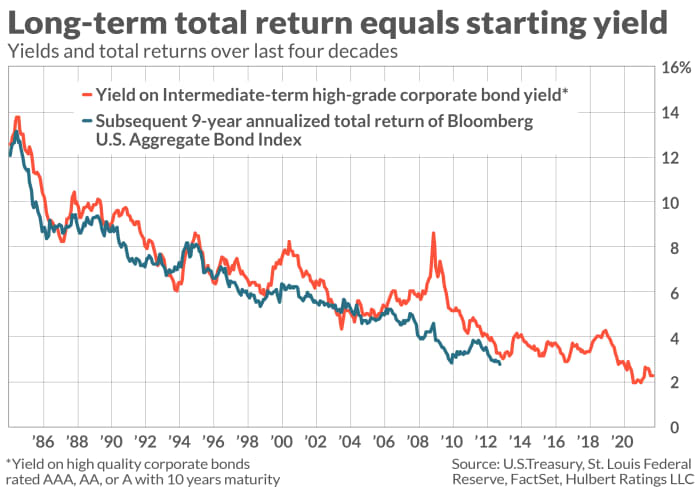

This chart plots the yields of intermediate-term corporate bonds for each month since 1984, along with what your total return would have been for each of those months had you bought and held for nine subsequent years. Notice how remarkably close is the correlation between the two.

To pick a specific example, focus on June 2003, at which point the yield on intermediate-term corporates was 4.3%. That yield represented a multiyear low, and over the next five years that yield would double to 8.6%. Nevertheless, as you can see from the chart, that starting yield was closely correlated with what your total return would have been (5.1% annualized) had you invested in the fund in June 2003 and held for nine years.

To be sure, as you can also see from the chart, the two series aren’t perfectly correlated. I chalk that up not to a failure of the formula but because the data series I chose when constructing the chart don’t represent precisely the same set of bonds.

The Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index, for example, incorporates U.S. Treasurys as well as corporate bonds, so it’s not a perfect reflection of the corporate bond market. Furthermore, its average duration isn’t precisely five years. I nevertheless chose the particular data series that appear in the chart because only with them was I able to retrieve many decades of history.

Favor intermediate-term bond funds

Regardless, notice the investment implication of the formula for how long you need to hold a bond ladder to be immunized from the impact of higher rates: Stick with intermediate-term bond funds. The required holding time with long-term bond funds exceeds most of our investment horizons.

Consider the Vanguard Long-Term Treasury ETF, with its 18.1 year average duration. Per the formula, you would need to hold this fund for 35 years to be indifferent to the path interest rates take from here. That’s an awfully long time.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com