This post was originally published on this site

There’s a whole host of goods rocketing in price, as evidenced by U.S. consumer prices matching a 30-year high in September with 5.4% year-over-year growth.

That makes sense. The COVID-19 pandemic, and the policy response of lockdowns and government stimulus, unleashed a massive switch in spending from services to goods. Spending on U.S. durable goods, in March, was 26% above its pre-pandemic trend.

“Suffice to say, a 26% excess demand for durable goods cannot be satisfied by a modern manufacturing sector that utilizes just-in-time supply chains and negligible spare capacity! As surging demand met relatively fixed supply, the price of durable goods skyrocketed to the current 11% above its pre-pandemic trend,” said Dhaval Joshi, chief strategist of BCA Research’s Counterpoint.

The surprise however has been the stickiness of services prices. That, Joshi explained, is because it wasn’t a classic demand shock. There was no point in services companies reducing prices because their customers couldn’t get those services anyway. “Meanwhile, statisticians continued to record the seemingly unaffected price of eating out or going to the theater, even though most restaurants and entertainment venues were shut,” he said.

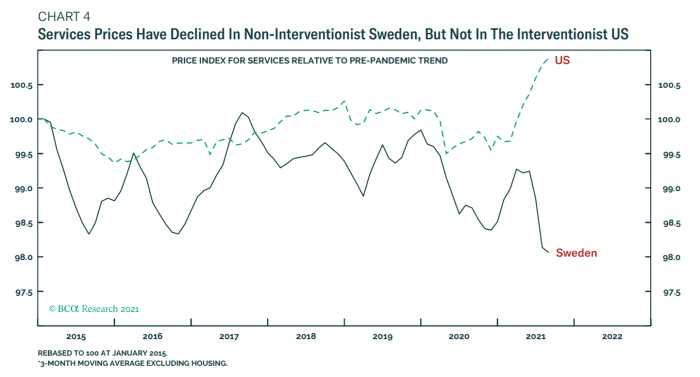

There’s one notable country that didn’t mandate shutdowns or lockdowns — Sweden. And there, services prices did decline. And now, inflation in Sweden is about 3 percentage points less than in the U.S.

What the Swedish experience suggests is that prices will eventually stabilize. “The surging demand for durables is correcting. Since March, it is already down by 15% but requires a further 7% decline to reach its pre-pandemic trend, which we fully expect to happen. After all, there are only so many smartphones and used cars that you can own,” Joshi said.

As for services, there are two forces — the wage rises as a result of the rocketing price of goods, but the deflationary force of hybrid home and office working, which will make it difficult for services spending to reach its pre-pandemic trending.

Joshi recommended underweighting durables-heavy consumer discretionary sector, underweighting commodities that haven’t sharply corrected versus those that have, and staying overweight U.S. Treasury bonds versus Treasury-inflation protected securities.