This post was originally published on this site

One of the more trite sayings about the profession of journalism is that it’s supposed to “afflict the comfortable” and “comfort the afflicted.”

That sounds nice, but you know who else should be doing that? Our politicians. Isn’t it the job of those we send to Washington to look after their constituents—the people they claim to represent?

But this really isn’t how it works. Money talks, and the powerful and comfortable, through lobbyists and big campaign contributions that often don’t have to be disclosed (appropriately, this is called “dark money”) have a far easier time influencing the political process and getting the outcomes they want than those who lack this kind of clout.

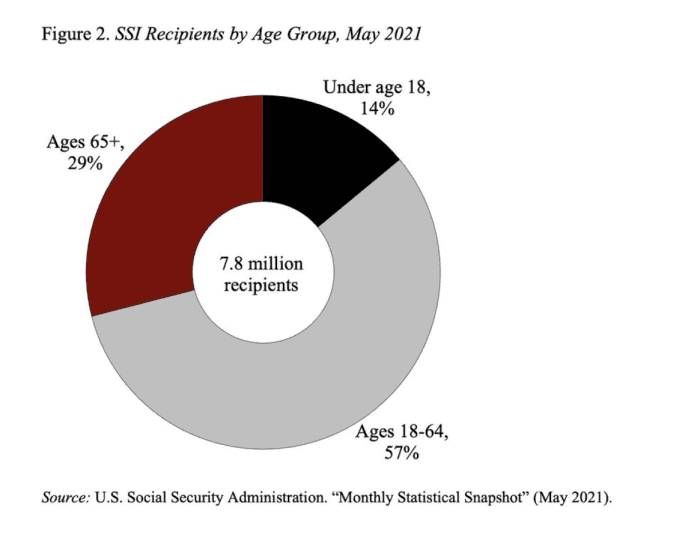

One of the better examples of this concerns the 7.8 million Americans who receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) each month from the government. The program, which dates to 1972, is designed to comfort the afflicted—low-income elderly and/or low-income disabled citizens.

Who do you think gets more attention in Congress? The elderly and disabled poor, or the fat cats in their bespoke suits stuffed with campaign cash?

This helps explain why federal benefits for aged, blind and disabled Americans haven’t been updated in years. So little attention has been paid to SSI that a key Senate committee with oversight of the program just held its first hearing on it in a quarter-century. Kudos to two senators—Ohio’s Sherrod Brown and Oregon’s Ron Wyden (both Democrats) for reviving attention to this vital federal program.

One problem is that unlike Social Security itself, which is funded from payroll taxes, SSI is funded from general tax revenues, and thus more politically vulnerable to the whims of Congress. This means an air of uncertainty is always hanging over the heads of those who depend on it.

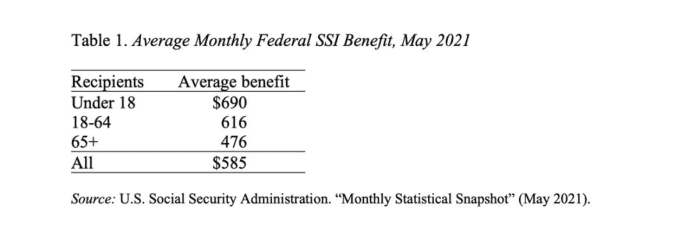

The support they get is modest. As of August, the average monthly SSI benefit is $585.96. But imagine being, say, poor and blind, and unable to earn a decent income and provide for the basics. A few hundred bucks, while welcome, isn’t going to make much of a difference in a life filled with considerable hardship (about 2.3 million of SSI’s recipients are also old enough to receive basic Social Security itself, which has an average monthly benefit this year of $1,555). In the table below, you might notice that benefits for children are higher. That’s because they typically have no income of their own. And in every case, benefits are cut by a third for beneficiaries who live in another person’s household without paying for shelter or food.

Since Congress hasn’t done anything about SSI in years, Brown thinks it’s way overdue for an overhaul. His “Supplemental Security Income Restoration Act of 2021” (S-2065), introduced in June, aims to, among other things, update and expand who is eligible for SSI. He wants to boost benefits by nearly a third and let them grow beyond inflation each year (merely indexing benefits to inflation doesn’t allow them to get ahead in real terms).

It would also eliminate 20th-century rules that slow up benefits, and repealing savings and income limits for recipients. For example, a 1989 provision says that an individual SSI beneficiary can have up to $2,000 in savings, and $3,000 for a couple. Brown wants that raised to $10,000 per individual and $20,000 per couple.

Here’s another outdated rule Brown hopes to scrap: If a SSI recipient works they can currently keep up to $65 of their earnings each month. Just $65. Earnings above that threshold cut benefits by 50 cents on the dollar. Brown’s bill would allow them to earn up to $399 from work. All this could, projects the Urban Institute, a left-leaning Washington think tank, help lift an estimated 3.3 million people out of poverty.

The senator, who didn’t respond to a call for comment, has called SSI America’s “forgotten safety net.”

But it’s not forgotten by those who need it. Mary Johnson, Social Security and Medicare policy analyst for the Virginia-based Senior Citizens League, an advocacy group, tells me SSI is a common worry for the seniors she hears from.

“They don’t get enough,” she says. “Not enough to pay the rent. Not enough to keep up with utilities, prescriptions and food prices.”

And again: There are millions of needy non-seniors—poor, disabled, often unable to work—who also rely on the program.

But besides a few Congressional lefties, modernizing Supplemental Security Income is an idea that hasn’t gained much traction. Beyond one hearing, it hasn’t gone anywhere in the Senate, overshadowed by bigger issues like an infrastructure bill (which has passed the Senate but bogged down in the House) and the president’s gargantuan $3.5 trillion social spending bill.

Why not attach S-2065 to Biden’s wish list? It might seem logical, but the president himself acknowledges that Congress will never approve $3.5 trillion in spending; he said Friday that something in the neighborhood of $2 trillion might be feasible. But West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin—a conservative Democrat with the power to scuttle Biden’s agenda—has said $1.5 trillion is more like it. There simply might not be room to boost SSI.

What’s funny here, and I’m being sarcastic, is that Manchin and another conservative Senate Democrat, Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema have already cut some of Biden’s corporate tax proposals down to size. Is it a coincidence that both have raked in contributions from groups who want those rates lowered?

If only the poor and disabled had that kind of clout.