This post was originally published on this site

If you think a bear market can’t happen while the U.S. economy is growing, think again.

It certainly would be nice if economic growth provided reliable protection from bear markets. The Conference Board, for example, projects that real U.S. GDP growth for all of calendar 2021 will be 6.6%. Bank of America is projecting a 6.5% growth rate. Both estimates are more than double the 2.7% annualized average growth rate over the past 50 years.

The occasion to disabuse you of any wishful thinking about bear markets and economic growth is the National Bureau of Economic Research’s recent pronouncement that the pandemic-induced recession came to an end 15 months ago. Since the bear market on Wall Street came to an end at almost precisely the same time, you’d be excused for thinking that the two are highly correlated.

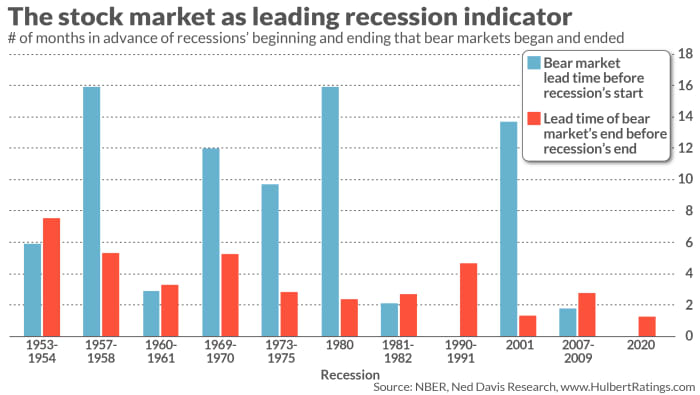

But you’d be wrong, for two reasons. The first is that the stock market anticipates recessions by a number of months. That means the economy almost always will still be growing when a bear market begins. This is illustrated in the chart below, which reports the bear market lead times for U.S. recessions since 1950. On average, the corresponding bear markets began 7.2 months before the recessions.

The same goes for when recessions end — as you can also see from the chart. Though the lead times for recessions’ ends are shorter than for when they begin, the average is still 3.6 months. This means that new bull markets begin while the economy itself is still contracting.

In both cases, you learn little about the stock market’s major trend from whether the economy happens to be expanding or contracting. Put another way, the stock market is forward looking, anticipating what’s coming down the pike. What’s happening right now has long since been baked into stock prices.

The second reason you’d be wrong for thinking a bear market can’t occur when the economy is growing: some bear markets are unaccompanied by any recession whatsoever. This was true, in fact, in nine separate cases since 1950, according to a bear-market calendar maintained by Ned Davis Research.

This is the source of the late Nobel-winning economist Paul Samuelson’s famous quip that the stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions. But his wisecrack isn’t entirely fair; it assumes that the sole reason a bear market will occur is economic weakness, and this is not the case.

One additional possible cause of a bear market is that equities sometimes get too far ahead of fundamentals. In such cases, the economy could continue growing even while stock valuations come back to earth. That’s especially important to keep in mind currently, with the stock market either more overvalued than at any time in U.S. history, or nearly so.

Another possible cause of a bear market while the economy continues to grow: an exogenous event that doesn’t have widespread economic impact. An example of this was the bankruptcy of Long Term Capital Management in the summer of 1998, which led to the S&P 500

SPX,

falling 21% on an intra-day basis over a six-week period.

Regardless, the investment implication is clear: A bear market could begin at any time, regardless of how strong the economy appears to be.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

Also read: Here’s another sign the bull market is near a peak, and this one bears watching

Plus: Why many stock investors worry when this market indicator gets as high as it is now