This post was originally published on this site

In 1998, 46 states and several U.S. territories came to a groundbreaking settlement with major tobacco companies. The “Master Settlement Agreement” set rules restricting tobacco marketing and sales, while also requiring the industry to pay states billions of dollars annually — amounts intended to help local governments defray the economic toll stemming from tobacco use.

But 23 years later, as states finalize their fiscal 2022 spending plans, those tobacco settlement revenues are generally being counted on to balance the budget — not to fund stop-smoking programs or treat smoking-related health problems, such as lung cancer, even as an alarming uptick in vaping among high schoolers has anti-tobacco groups worried.

Kentucky plans to balance its general fund budget next year with $103 million from its tobacco settlement revenues. In Kansas, settlement revenues will go toward “various children’s programs.” And Connecticut counts its money as just another general fund revenue source.

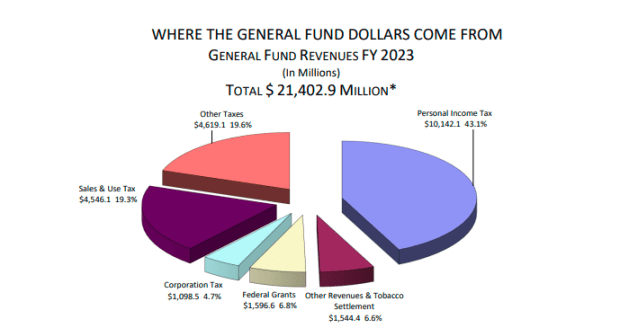

Source: FY 2022-2023 Governor’s Budget, Connecticut

“For virtually every single state this is about saving money,” said John Schachter, who runs the state advocacy effort at the national Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. “The states are being penny-wise and pound-foolish in terms of public health and money spent.”

When the master settlement was signed, initially with behemoths Philip Morris

PM,

R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. and two other companies, the intention for the revenues was clear. Striking a deal “will achieve for the Settling States and their citizens significant funding for the advancement of public health, the implementation of important tobacco-related public health measures,” the MSA says.

But it’s up to each state to interpret that language as they wish, and it generally falls to nonprofits like the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids and others to track what gets spent — or not.

Those statistics are grim. According to Tobacco-Free Kids’ most recent annual report, released in January, states will collect $26.9 billion from the tobacco companies in Fiscal Year 2021, but spend only 2.4% of it, or $656 million, on cessation and prevention initiatives.

That $656 million is barely one-fifth the amount that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the states spend. “Not a single state currently funds tobacco prevention programs at the level recommended by the CDC,” the report adds.

Some years ago, as the number of Americans who smoked continued to decline, it might almost have been time to declare victory, Schachter said in an interview.

But as e-cigarettes have gained in popularity, particularly among young people — some reports put the number of high-school student using them at nearly 20% —Tobacco-Free Kids and other groups are feeling just as vigilant as ever.

“We know that investing in these programs is financially wise,” Schachter said. “It will keep kids and others from smoking and, ultimately, in the long term bring down healthcare costs. But it is a long-term process, and if a state moves the money elsewhere, they can see that impact now.”

The MSA’s legacy has been disappointing enough that advocates say it shouldn’t serve as a template for future settlements. As money starts flowing from agreements to end opioid-crisis lawsuits, some caution that any such settlements should have more teeth. “Make sure you put in details about how much should be spent and on what,” Schachter said.

In a moment of heightened sensitivity toward racial and economic inequalities, it’s also worth noting the disparate impact tobacco has: Americans with lower income and less education are more likely to smoke, as are “residents of the Midwest and the South, American Indians/Alaska Natives, LGBTQ Americans, those who are uninsured or enrolled in Medicaid, and those with mental illness,” the 2021 Tobacco-Free Kids report notes.

“Black Americans die at higher rates from smoking-caused diseases, in large part due to the tobacco industry’s predatory targeting of Black communities with menthol cigarettes,” according to the report. Recommitting to tackling tobacco as a public-health issue could be a step toward racial justice, in other words.

Read: Flint water crisis victims will receive $641 million. Just don’t call it ‘justice’