This post was originally published on this site

Months after an electric grid outage in Texas left hundreds dead and millions of homes without power for weeks, the state of Maine is eyeing a big change to the way its residents receive their electricity.

A bill currently being considered by the legislature would create a “consumer-owned” electric utility, in effect taking over the grid from two existing investor-owned utilities and turning it over to be managed by a nonprofit entity.

Such a step, called “municipalization,” has rarely been accomplished, and never on a state level. But amid high prices, unreliable service and a growing desire to make existing infrastructure more environmentally friendly, frustration with corporate utility ownership is rising. That suggests the experiment in Maine may be repeated elsewhere.

“There’s probably a higher level of interest in using the municipal model now than there’s ever been, but it’s also becoming more challenging to accomplish it,” said Steven Weissman, a lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley law school.

Read: Texas governor says new laws fix power-grid problems, but experts disagree

Nearly all Maine residents currently get their power from one of two large investor-owned utilities, Central Maine Power and Versant. Both rank dead last for consumer satisfaction among electric utilities nationwide, according to the group sponsoring the legislation, and households they serve pay 58% more for electricity than the remaining 4% of Mainers, who get power from small consumer-owned utilities.

In fact, while cost isn’t the first or only consideration for many proponents of municipalization, some recent research suggests that regulators may feel they have to authorize utilities to charge customers higher rates in order to attract the kind of capital they argue they need to maintain or upgrade infrastructure.

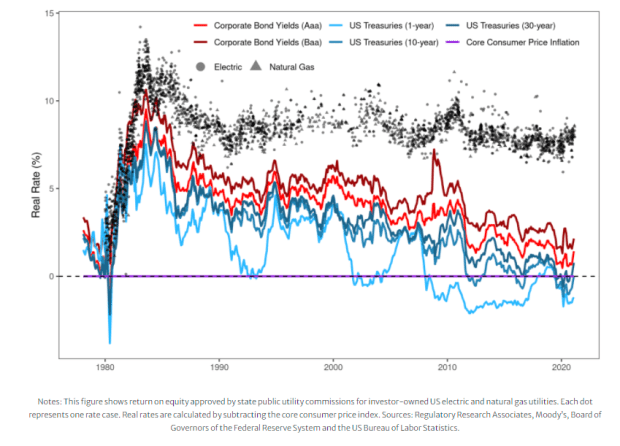

Research from Karl Dunkle Werner and Stephen Jarvis at the Haas School at California-Berkeley shows historical rates of return for electric utility investors have remained higher than other types of fixed income.

Private companies see those kinds of returns as worth fighting for, said Weissman, who is a proponent of municipalization. And they allow investor-owned utilities to contribute to area politicians, flood local airwaves with ads designed to sway public opinion and generally just outlast municipal efforts at takeovers, he said.

That’s what happened in Boulder, Colo., said John Farrell, co-director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, where a decade-long effort to municipalize failed in 2020. It was “politically exhausting,” Farrell told MarketWatch.

ILSR advises Our Power, the umbrella group advocating for the Maine transition.

In an emailed statement, a Central Maine Power spokesperson said, “This unprecedented government takeover will cost Mainers $13.5 billion, raise electric rates for decades to come and severely delay needed investments to fight climate change. We agree with the three former (Public Utility) Commissioners who have served administrations led by both parties, who strongly oppose it, and point to Governor Mills, who has said that this is a very complicated issue to send to voters and at the very least more study is needed.”

Central Maine Power’s parent company is Iberdrola, a multinational headquartered in Spain which lists the sovereign wealth fund of Qatar, the central bank of Norway, and BlackRock Inc.

BLK,

as its largest shareholders.

It’s not clear how much the transition would actually cost, in part because the state of Maine would likely have to seize the assets of both utilities by eminent domain, in effect paying top dollar for them. Weissman points out that such up-front costs may be relatively inexpensive for municipal governments who can borrow in the tax-free bond market.

A Versant spokesperson sent their own response: “A government power takeover will threaten our state’s ability to do the work our citizens demand to keep pace with an evolving energy landscape. When discussing the costs of this proposal, we can debate the dollar amount — which certainly would stretch into the billions — but the societal and environmental costs of delay and inaction it would cause are unlimited. This bill would actually still require we pay an investor-owned utility to manage and run our electrical system, and does not guarantee lower rates or better reliability for customers.”

Versant is owned by the Canadian company Enmax, which describes itself as a “private corporation…whose sole shareholder is The City of Calgary. Calgary’s City Council acts in the capacity of the Shareholder.”

Ed Hirs, a longtime energy economist and a fellow at the University of Houston, says there’s merit in Versant’s argument. Consumers are inclined to say they want sustainability and reliability, until those costs show up in their household bills.

“If you can give the voting public cheaper rates, it’s just a matter of time before physical deterioration catch up with you,” Hirs said.

Beyond that, Hirs thinks the Maine effort is misguided. “This is exactly what Mexico, Venezuela and other such countries have done when the government sees an opportunity to take control of a particular asset presumably with the idea of doing things better for the populace,” he said in an interview.

Still, Farrell and other advocates believe that municipally-owned utilities do have better outcomes for residents since they are more accountable locally. “We talk about this kind of thing as really important leverage and a check on companies that otherwise don’t have competition,” he said, noting that 35 states have rules shielding private utilities from competition.

Opinion: America Needs an Infrastructure Bank

He and Weissman both call themselves hopeful that what’s happening in Maine will be just the beginning. Indeed, an industry group called the American Public Power Association says it is seeing increased interest in the idea of municipalization, in large part because of increased desire for more environmentally-friendly power options.

The effort in Maine is driven in part by a desire to switch to renewable sources of energy, which could run in the billions, the municipalization proponents say.

But Farrell thinks some sort of compromise is more likely than the long fight to disentangle municipalities from private companies. One reason Boulder abandoned its effort was that its utility company had slowly started switching its reliance to renewables.

Many households in California are served by what’s called community choice programs, where municipalities can opt into regional groups.

He likens the movements underway in the utility space to those in the high-tech platform world. Could “the grid” be open-source, rather than owned by any one entity?

“We don’t talk about platform monopolies in electricity even though we’ve created them by law all around the country,” Farrell said. “I think this is a reckoning on whether or not we should continue to grant those or we should take back the network.”