This post was originally published on this site

Washington lawmakers considering President Joe Biden’s $2.3 trillion infrastructure package are interested in reviving a program born out of the response to the last recession, even as the state and local governments that it’s meant to help are much more cool on the idea.

The Build America Bond program, created as part of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, allowed municipal entities to issue debt with a federal subsidy. Over nearly two years, about $181 billion of bonds were sold for infrastructure needs, ranging from storm-water capital improvements in the city of Tampa, to building new school buildings in Omaha, Neb.

Unlike most of the $3.9 trillion municipal market, so-called BABs were taxable. That was a positive, because it made muni bonds attractive to a much wider range of investors, said Eric Kim, head of U.S. state government ratings for Fitch. Meanwhile, the federal subsidy –– 35% of the interest cost –– was meant to help state and local governments coming out of a grinding recession finance their projects.

“Democrats and Republicans are in agreement about bringing back the financing tool of tax credit bonds a la Build America Bonds,” wrote Washington-based Beacon Policy Advisors in a May 19 note. “It’s something that is supported by both Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) and Ranking Member Mike Crapo (R-Idaho) and is also a major priority for House Ways and Means Committee Chair Richard Neal (D-Mass.).”

But municipal-market participants are less enthusiastic.

“State and local issuers are deeply ambivalent about the BABs program,” said Matt Fabian, a partner with Municipal Market Analytics. “It’s being talked about like it’s the core of the infrastructure program, but issuers in general don’t care because demand for tax-exempt bonds is now the strongest it’s ever been,” he said.

“We are flooded with demand,” Fabian said.

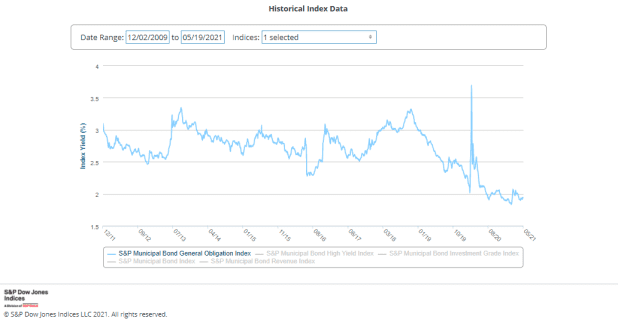

The yield on the S&P Municipal Bond General Obligation Index is currently about 1.93%, among the lowest on record back to 2009. Bond yields and prices move in opposite directions.

While Washington lawmakers may believe that a lower interest rate would help issuers, thereby boosting the amount of overall spending on infrastructure, MMA’s calculations show the federal subsidy would have to be at least as high as 50% to make BAB issuance worth it.

More to the point, Fabian told MarketWatch, “state and local infrastructure spending is a zero-sum game.” Governments only have so much in revenues to pay back bonds, no matter how low the interest rate.”

The legacy of the BABs program also suffers from a self-inflicted wound. Sequestration, the automatic budget cuts that kicked in when Congress couldn’t agree on a budget in 2012, also reduced the federal subsidies governments had relied on when they issued the debt.

“There will definitely be some hesitancy on the part of governments to participate in a program that has any kind of ongoing subsidy from the federal government because of what happened with sequestration,” Kim said.

Ratings agencies like Fitch are watching the growing backlog of infrastructure needs for states and locals, Kim said in an interview, and it’s clear governments will need to think creatively about solutions, whether by joining with the private sector, requesting outright grants from the federal government, or even raising taxes on their own.

Read next: In one chart, how U.S. state and local revenues got thumped by the pandemic—and recovered