This post was originally published on this site

The Issue:

The coronavirus pandemic has spawned enormous changes, from economic distress and high unemployment to disrupted schooling and tragic public-health outcomes. Even before stay-at-home orders were issued in many places and before there were large numbers of confirmed infections, there was a massive decrease in reported rates for almost all types of crime.

In the months following the initial lockdowns, as people adjusted to the new normal and cities started to ease COVID-related restrictions, crime rates in the U.S. continued to follow very different patterns compared with previous years. However, the magnitude of the impact has varied by type of crime and there have been notable exceptions: while overall crime rates are lower than they have been in past years, homicides and shootings are much higher than usual.

What accounts for these changes, and what can we learn from them?

The Facts:

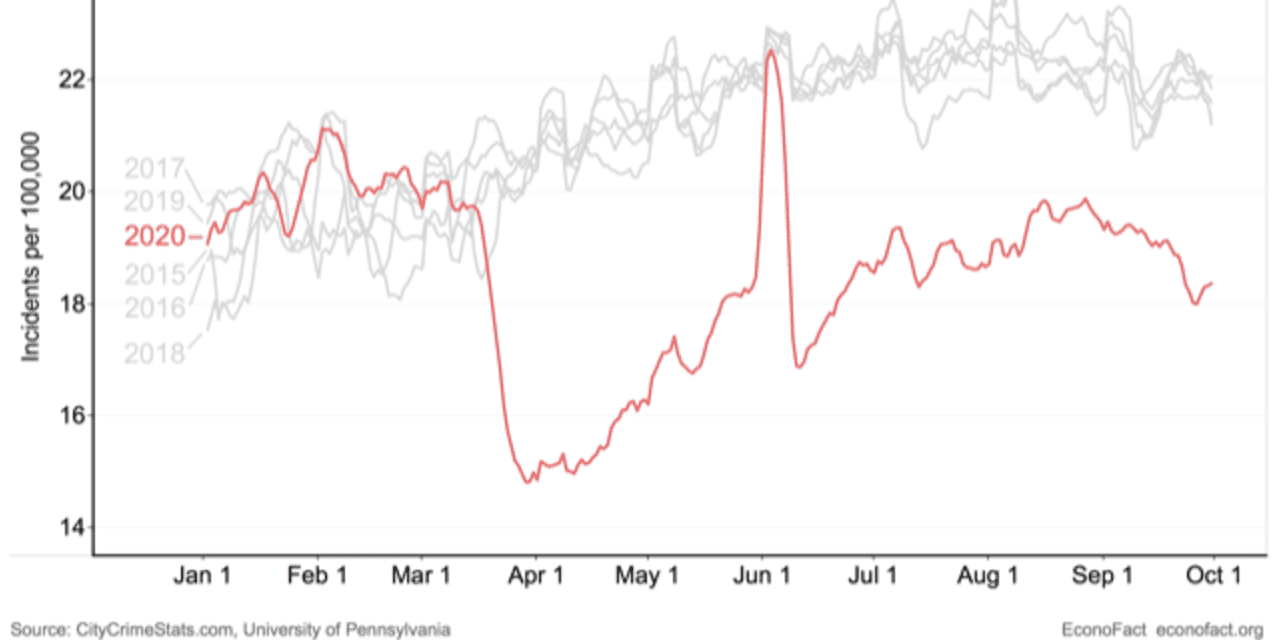

Overall, crime fell 23% in the first month of COVID lockdown and has since remained lower than usual. I examined crime rates in over 25 large U.S. cities in 2020 and compared those rates to past years. Across almost all of the cities examined, crime dropped substantially in the first month of the pandemic—with overall crime falling by over 23% relative to the average of the same period in the previous five years.

“

Our data show that the crime drop actually begins 10-14 days before the stay-at-home orders and is almost coincident with the mobility drop.

”

Moreover, crime rates have remained at significantly lower levels relative to previous years even after cities eased their COVID restrictions in late spring. I was able to observe the marked difference in crime rates since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic by assembling data on crime incidents, arrests, police stops, and shootings as well as COVID-19 incidence and mobility information. Detailed data is available at citycrimestats.com.

The overall drop in crime corresponds with a drop in the population’s mobility. Stay-at-home orders and business closures have meant that people are not driving, shopping, or walking around on the streets as much they normally would. Notably, our data show that the crime drop actually begins 10-14 days before the stay-at-home orders and is almost coincident with the mobility drop (these data come from individuals who have turned on location history for their Google account and use a mobile device). This is likely due to the fact that there was considerable media coverage before stay-at-home orders as well as some other less-restrictive orders already in place. The fact that the drop in crime coincided so closely with the drop in mobility suggests that the two are connected.

One reason why the easing of COVID-related restrictions appears to have had limited impact on crime rates is due to the fact that mobility in cities remained subdued even as the restrictions were lifted. While mobility picked back up from the lows seen in March 2020, it remained well below pre-COVID levels for the rest of the year as people were still unable to return to their normal routines.

Home burglaries dropped while commercial burglaries and car thefts rose. While it is often difficult to identify causes of crime, the discrepancy in types of burglaries suggests that reduced mobility had a pronounced effect on the types of crime people were committing. As the pandemic hit, people began spending far more time at home and one result of this is a large 24% decline in residential burglaries.

With people at home, that also meant there were fewer eyes on nonresidential buildings, which led to an increase in those burglaries—by around 38% on average across the cities examined. Similarly, people using their cars far less during the pandemic than they normally would meant that cars are left parked and unattended longer and car thefts have increased. In Philadelphia, for instance, the car theft rate after the pandemic hit was over 2.5 times as high as before.

Drug crimes dropped the most—by 65%—at the pandemic onset and fell again during the summer. Drug crimes saw the biggest decline of any category at the onset of the pandemic in almost all cities for which I have data—65% on average. However, the fact that fewer drug crimes are reported does not necessarily mean that there are fewer people engaged in drug-related activity.

Unlike most other crimes, drug crimes are often reported directly by police, rather than citizen reports to police, and there is evidence that police presence and enforcement of certain laws decreased during the pandemic onset. For example, police in Philadelphia stopped low-level arrests at the beginning of the pandemic to prevent further overcrowding in jails. While drug crime reports did start to revert at the end of spring, there appears to have been a second drop at the start of summer coinciding with the George Floyd protests, which possibly reflects a change in the policing of these crimes.

The drop in overall crime rates masks the rise in the rate of some violent crime beginning in the summer of 2020. There were substantial increases in homicides and shootings beginning in the summer of 2020, but it is not possible to tell whether this is due to the pandemic or other factors. The start of this spike in some violent crimes coincided with the protests associated with the police killing of George Floyd and continued through the summer and into the fall. This time period was also shortly after lockdowns ended in many places.

However, it is very difficult to pinpoint the cause of the spikes in homicides and shootings. For one thing, any theory to explain this pattern would also have to account for the fact that other violent crimes, such as robberies, were still down during this period. In large cities, an appreciable share of homicides and shootings are related to drugs or gangs and those likely to be involved in these crimes may not be deterred by stay-at-home orders or the prospect of disease.

The data show that rates of homicides and shootings, unlike other crimes, were initially unresponsive to COVID-19. Changes to the status quo in certain types of crimes that are associated with shootings and homicides could have led to turf wars that may explain some of the phenomenon of higher violent crime rates. This could also have been impacted by changes in policing or various changes brought on by the pandemic—but more research is needed to come to a firmer conclusion.

These changes in crime rates are likely not just due to changes in reporting rates. Two separate strands of evidence suggest that much of the crime change is not simply due to changes in reporting rates. First, there is not a large change in the share of crime reported by police versus the public, in the two cities that report this data.

If the pandemic were mainly changing reporting behavior, one would not expect the pandemic to affect reporting behavior for police in the same way it would affect reporting behavior for the general public. Thus the fact that the shares of reporting by both groups remain largely unchanged would suggest that they likely reflect changes in underlying crime. Second, in Philadelphia there was evidence of a drop in crime that varied as a function of distance from closed bars for simple assaults, robberies, and thefts—crimes that are more likely to happen near bars when the businesses are open, attracting customers and with alcohol playing a role in aggressive behavior. However, the same relationship was not found for drug crimes, which are unlikely to be impacted by distance from closed bars. This contrast suggests that a large portion of the change in reports reflects a real change in crime, and not just a change in reporting rates.

What This Means:

The onset of the pandemic in the U.S. in 2020 had a massive impact on crime, with large drops in almost all types of crime except for homicides and shootings. It led to a decline in both violent and property crime by 19% overall. The effect on drug crimes was substantially larger—about a 65% drop on average in the cities examined. The decline in crime began before stay-at-home orders and coincided closely in time to the substantial drop in mobility.

At this writing, the pandemic is still raging in the US. As such, political leaders, law enforcement, as well as individuals will need to account for the changed circumstances as they make decisions for some time to come. The hope is that these initial findings about the pandemic’s impact on crime will help inform decisions on allocation of police resources as well as individual precautions. In ongoing work I am also investigating how these unique events may help us better understand the factors that impact crime in normal times as well.

This commentary was originally published by Econofact—Crime in the Time of COVID.

David S. Abrams is a professor of law, business economics and public policy at the University of Pennsylvania. His research interests include the law and economics of crime, intellectual property, and health economics. Follow him @davidsabrams.