This post was originally published on this site

Which of the following two warnings would do the better job of preventing investors from paying too much attention to an investment’s recent performance?

- Past performance does not guarantee future results

- Future performance may be lower or higher than the performance data quoted

The first warning is what’s currently required in all investment advertising. The second is a proposal that the Securities and Exchange Commission is considering adding to the first.

In fact, both of these warning labels do a poor job. According to a recently published study, neither effectively dissuades investors from believing that an investment adviser on a hot streak will be able to continue doing so.

This belief, which is widespread, is referred to as the hot-hand bias or the hot-hand fallacy. Those guilty of it believe that, between two funds with identical long-term performance, the one whose more recent performance is superior is the better bet for future performance.

This new study appeared in the Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. Entitled “Fooled By Success: How, Why and When Disclosures Fail or Work in Mutual Fund Ads,” the study was authored by Professors Joseph Johnson of the University of Miami, Gerard Tellis of the University of Southern California, and Noah Van Bergen of the University of Cincinnati.

The researchers reached their conclusions after conducting a series of elaborate experiments in which investors had to choose between various hypothetical mutual funds. The funds were otherwise identical except for the sequence of their quarterly returns. In some cases that sequence was random, while in other cases the funds exhibited a pattern of increasing performance over as many as the trailing 11 quarters. The experiments also differed according to which of the two warnings was included.

The professors found that, regardless of the warning, investors preferred the fund that exhibited the longest pattern of improved returns.

They then surveyed the investors in these experiments as to their understanding of the SEC’s current warning. The professors found that, surprisingly, investors were not “ignoring or misunderstanding” it. Instead, Tellis told me in an interview, they were misapplying their understanding. They were interpreting the warning to mean that, while past performance does not “guarantee” future performance, it still is a helpful guide.

Warning signs

To prevent this misapplication, a more strongly-worded warning would be needed. But what, exactly? The professors attempted to answer this question by studying other possible disclosures. They tried this:

-

“Scientific research has shown that index funds, such as the S&P 500

SPX,

-0.09% ,

outperform managed funds over the long term.”

But this wording did not lead to a significant attenuation of the hot hand fallacy.

Here’s the warning that did reduce investors’ belief in a hot hand:

- “Scientific research has shown that mutual funds cannot perform any better than luck. So their past performance is irrelevant.”

Tellis said that “such a strong statement is needed” to counter investors’ belief in hot hands.

Should the SEC adopt this more strongly worded warning?

Should the SEC adopt this more strongly worded warning? That question is not as easily answered as you might think. On the one hand, shorter-term track records are overwhelmingly statistical noise. A fund that has done well over the recent past is no more likely to be a good choice for the future than one which has done poorly.

On the other hand, it’s going too far to say that past performance is totally irrelevant. At least some research has found that, even though past performance is largely uncorrelated with subsequent performance, it is not completely so.

I have reported on some of this research before. In one study, for example, 98.3% of a portfolio’s ranking in a given year was found to be due to factors completely unrelated to its prior performance. Another found this percentage to be 91.8%. Though neither study leaves much room for past performance to explain or predict much, it doesn’t mean there’s no such room whatsoever.

As a matter of public policy, therefore, the SEC would probably be going too far to adopt the more strongly worded warning offered in this new study.

It nevertheless would serve most investors well to internalize the spirit of the professors’ strongly worded warning — especially in regards to shorter-term performance.

To show this, consider what I found when searching for hot hands among the investment newsletters my auditing firm monitors. Specifically, I imagined myself five years ago, at the beginning of 2016, deciding between various newsletters according to the strength of their hot hands up until that point. Following loosely the lead of this recent study, I focused on the trailing 11 calendar quarters through the end of 2015, calculating for each newsletter the number of those quarters in which they had beaten the overall stock market.

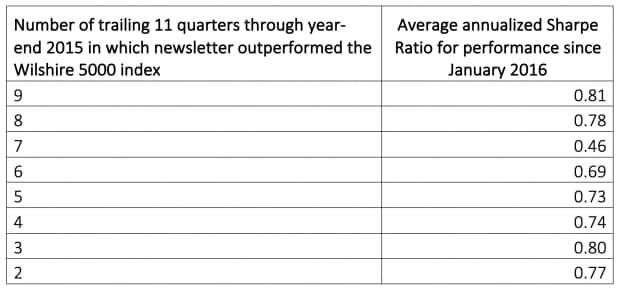

The table below shows these newsletters’ performance over the five years since the beginning of 2016, as a function of the number of trailing calendar quarters of market outperformance. The metric I used is the Sharpe Ratio, which reflects risk-adjusted performance.

At the 95% confidence level that statisticians often use when determining if a pattern is genuine, there is no statistically significant correlation between the number of quarters of market-beating return and subsequent performance. The average Sharpe Ratios fall in a small range, regardless of how many calendar quarters prior to the end of 2015 in which the newsletters beat the market.

The bottom line: Short-term performance plays a depressingly modest role in explaining which advisers and funds will perform the best in the future. Even if you don’t go so far as to say that past performance is completely irrelevant, your default choice should be index funds.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: Here’s more evidence that the next decade for stocks won’t be as good as the last