This post was originally published on this site

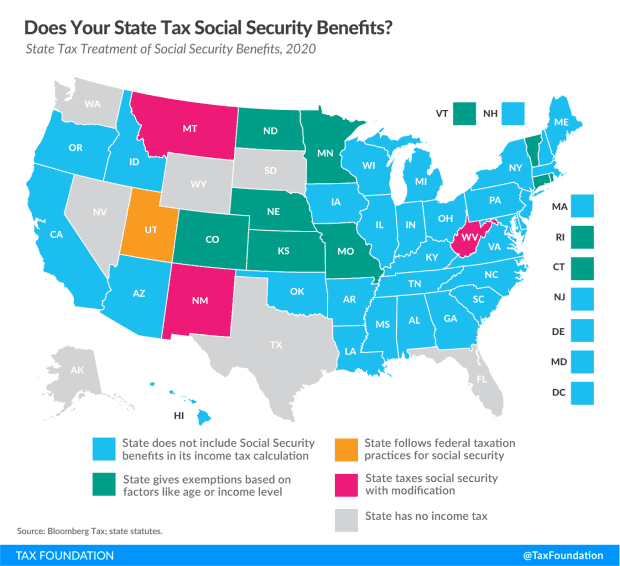

The question, “Does my state tax Social Security benefits?” may be simple enough, but the answer includes a lot of nuance.

Many states have unique and specific provisions regarding the taxation of Social Security benefits, which can be broken into a few broad categories. That’s what we do with this week’s map.

Thirty-seven states and Washington, D.C., either have no income tax (Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington and Wyoming) or do not include Social Security benefits in their calculation for taxable income (Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Delaware, Washington, D.C., Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and Wisconsin.)

New Mexico includes all Social Security benefits in the taxable income base, though the state provides a deduction that reduces the taxability of all retirement income.

Utah taxes Social Security benefits in the same way as the federal government. Under the federal tax code, the taxable portion of Social Security income depends on two factors: a taxpayer’s filing status and the size of their “combined income” (adjusted gross income plus nontaxable interest plus half of Social Security benefits). In general, if a taxpayer has other sources of income and a combined income of at least $25,000 (single filers) or $32,000 (married filing jointly), Social Security benefits are treated as income for taxation purposes.

It should be noted that the state also provides a nonrefundable retirement tax credit (this does not apply to survivor or disability Social Security benefits).

Several states reduce the level of taxation applied to Social Security benefits depending on things like age or income level:

Colorado allows taxpayers to subtract some of their pension income as long if they are age 55 or older under the “pension and annuity subtraction.”

Connecticut excludes Social Security benefits from income calculations for any taxpayer with less than $75,000 (single filers) or $100,000 (filing jointly) in adjusted gross income (AGI).

Kansas provides an exemption for such benefits for any taxpayer whose AGI is $75,000, regardless of filing status.

Minnesota provides a graduated system of Social Security subtractions that kicks in when what it calls provisional income is below $81,180 (single filer) or $103,930 (filing jointly).

Missouri allows a 100% Social Security exemption as long as the taxpayer is 62 or older and has less than $85,000 (single filer) or $100,000 (filing jointly) in annual income.

In Montana, some Social Security benefits may be taxable, and the state advises taxpayers to fill out a worksheet to determine how the state taxable amount differs from the federally taxable amount.

Nebraska allows single filers with $43,000 in AGI or less ($58,000 married filing jointly) to subtract their Social Security income. If their income is over that threshold, the state follows the federal treatment.

North Dakota allows taxpayers to deduct taxable Social Security benefits if their AGI is less than $50,000 (single filer) or $100,000 (filing jointly).

Rhode Island allows a modification for taxpayers who have reached full retirement age as defined by the Social Security Administration and have a federal AGI of under $81,900 (single filer) or $102,400 (filing jointly).

Vermont provides a graduated system of Social Security exemptions that kick in if a taxpayer’s income is below $34,000 (single filer) or $44,000 (filing jointly).

West Virginia passed a law in 2019 to begin phasing out taxes on Social Security. Beginning in tax year 2020, the state exempts 35% of benefits. In 2021, that amount increases to 65%, and in 2022, the benefits will be completely exempt.

Janelle Cammenga is a policy analyst with the Tax Foundation, a tax policy research organization in Washington, D.C.