This post was originally published on this site

Every year, college seems more and more unaffordable.

The published price of tuition, room and board and fees for an in-state student at a public four-year college rose to nearly $22,000 annually last year and $48,380 at a private four-year institution, according to the College Board, which administers the SAT exam. That’s almost $90,000 for four years at public colleges and nearly $200,000 for a private college, roughly double what you would have paid 30 years ago. Elite, brand-name schools are even pricier: It cost nearly $75,000 a year to attend Stanford in 2019-2020.

Between need-based and so-called “merit” aid, few people pay full price. But even if you pay half of that, it’s $50,000 to $150,000 over four years, a stretch for many families, especially those who have two or three kids.

So is your child getting your money’s worth for those inflated tuition dollars?

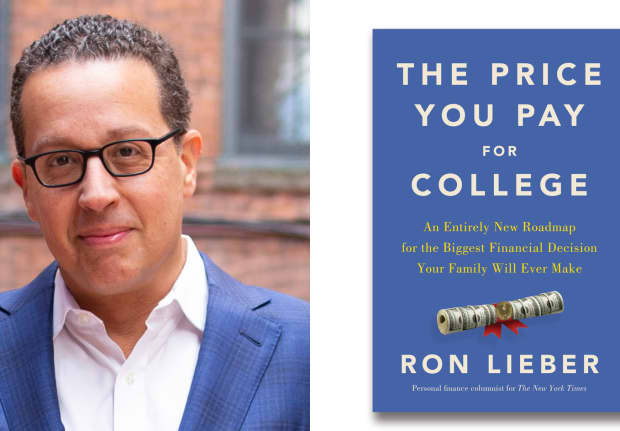

In a new book on all aspects of college planning, “The Price You Pay for College,” The New York Times’ Your Money columnist Ron Lieber revealed that the lion’s share of what you’re paying is not going into pricey frills like posh gyms, lazy rivers and climbing walls.

“The vast majority of the money that goes to educating undergraduates is for salary and benefits for the people who teach and the staff who support them,” Lieber wrote. Salary, benefits and health insurance account for some 60% of colleges’ budgets, he reported in his book.

Of course, some of that is the result of administrative bloat—increased marketing and admissions staffs, “enrollment management” consultants who figure out how much aid to give out to lure paying customers, and the legendary (but exaggerated) army of diversity deans enforcing the latest woke dicta and quotas.

According to the American Institute for Research, administrative positions have increased throughout higher education, and by 2012 administrators outnumbered full-time faculty.

Support services (largely administrative expenses) and instruction (overwhelmingly faculty salaries) each comprised about 30% of private four-year nonprofit colleges’ spending in 2017-2018, according to the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES). Support services were much lower at public four-year colleges (about 20%), probably because of state spending cuts.

So about a third of your tuition dollars goes to salaries and benefits for faculty members.

“You’ve got to train for a really long time to be a professor,” Lieber told me. “Economics 101 says they’re going to expect to be compensated for that training. Those teachers earn above-average salary, and they tend to have reasonably generous benefits packages. It starts there.”

In 2019-20, full professors at state schools that offered Ph.D programs made an average $145,899 a year while full professors at private nonprofit institutions earned more than $200,000, according to the annual survey by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP). Even nontenured assistant profs average from $86,000 a year at state schools to $108,000 at four-year private institutions. Throw in $20,000 or so a year per person for benefits and health insurance and multiply all that by the number of full-time faculty, and it really adds up.

What do your kids get for all that? Maybe some help from career or mental-health counselors if they need it, but those famous profs who write books or appear on TV are busy, well, writing books or appearing on TV. Or publishing their research in academic journals for a small, rarefied audience of other scholars.

In his book, Lieber reported that nearly three out of every four faculty members at four-year colleges are not tenure-track faculty but instructors, lecturers and adjuncts who get paid by the class and often eke out a living shuttling between several schools. So many students won’t take classes from faculty superstars until their junior or even senior year.

And at many schools research production, not undergraduate teaching skills, drives decisions to grant tenure, academia’s brass ring. So the incentive is to do as much research and as little teaching as possible.

“All of the fancy professors who make all of the money that leads the tuition to be so high, often they’re jousting and jostling with one another to avoid undergraduates,” Lieber told me. “A good number of these professors are excellent scholars and produce amazing work, but really want nothing to do with teenagers.”

How to get around this distorted incentive structure? Lieber recommends checking out small liberal-arts colleges (he and I both went to one—Lieber to Amherst, me to Swarthmore) where there are no graduate students and teaching ability is prized more. Indeed, according to the AAUP, the highest salaries at 10 elite four-year private universities are as much as 40% more than they are at 10 prestigious liberal-arts colleges.

But small schools aren’t for everyone, which is why parents should ask a lot of questions on college tours.

Harper

“The question is, in which of these institutions are the professors there primarily to teach? How much is this institution at the end of the day really focused on undergraduates?” he said.

I’d also ask how much time do professors spend in the classroom and how much time students get to spend with them outside of class as well.

Because before you fork over more dollars than you ever thought you’d spend on college, it’s good to know whether students are getting what their parents are paying for.

Howard Gold is a MarketWatch columnist. No-Nonsense College appears monthly. Follow him on Twitter @howardrgold1.

More college coverage from MarketWatch

High-school students who take college classes don’t always save time — or money

This college professor spills 6 secrets that every freshman should know