This post was originally published on this site

Michael Tubbs is the youngest elected mayor of a major U.S. city and the first Black mayor of Stockton, Calif.

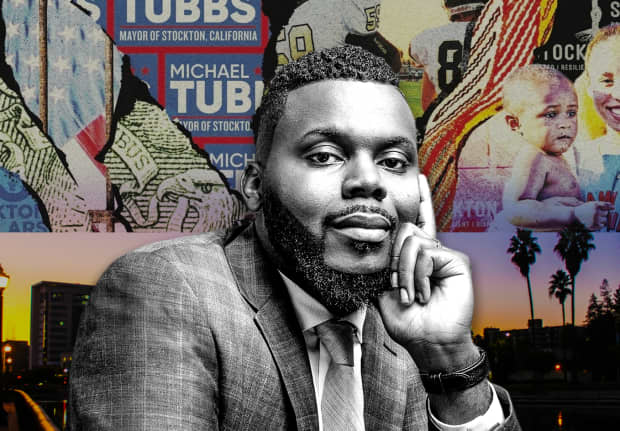

MarketWatch photo illustration/Michael Tubbs|HBO|iStockphoto

A Google GOOG, +1.58% GOOGL, +1.63% search of Stockton, Calif., a city located east of San Francisco, suggests that people also ask the following three questions:

1. “Is Stockton CA a dangerous city?”

2. “Why is Stockton so bad?”

3. “Is Stockton, California ghetto?”

Those likely result from the city’s once record-high violent crime rate, which in 2018 was the highest among 70 California cities with 100,000 or more residents, according to a Federal Bureau of Investigation report.

The city has also recorded record-high poverty rates: In 2015, nearly 22% of Stockton’s population of more than 300,000 people were living below the poverty line, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. By 2019, that share had fallen to about 15%.

But since Michael Tubbs became Stockton’s mayor in 2017 at the age of 26, making him the youngest elected mayor of a major U.S. city and the city’s first Black mayor, Stockton has added a new title to its résumé: pioneer in running a guaranteed basic income experiment.

In 2019, Stockton became the first major U.S. city to launch a guaranteed basic income experiment, in which 125 people who make less than $46,000 a year are being given $500 a month with no strings attached until January of 2021. The program, originally slated to end in July, was extended due to the pandemic.

The experiment received initial funding from the Economic Security Project, a progressive group launched after the 2016 election and co-founded by Facebook FB, +2.39% co-founder Chris Hughes.

Before the pandemic, few cities had plans to experiment with basic income. Now 25 mayors from U.S. cities, including Atlanta, Los Angeles and Philadelphia, have joined Mayors for a Guaranteed Income (MGI), a coalition formed in May and headed by Tubbs that advocates for direct cash payments. Twitter TWTR, +0.31% CEO Jack Dorsey donated $3 million to the initiative in July.

Compton, a city in Los Angeles County whose mayor is also part of MGI, recently announced the launch of a two-year guaranteed income experiment in which 800 low-income families will receive monthly payments with no strings attached.

Also read: The push for universal basic income is gaining momentum amid the pandemic

MarketWatch spoke with Tubbs, who is the subject of the recent HBO documentary “Stockton on My Mind,” as part of The Value Gap interview series:

MarketWatch: “Stockton on My Mind” focuses a lot on your upbringing, particularly the fact that your mom gave birth to you at 16 years old, and raised you without your father in the picture, given that he’s been serving a life sentence. To what degree does your upbringing shape the decisions you make as mayor?

Tubbs: Having a mother who had me young and single has given me a special appreciation for the contributions that women make to the labor force and to our city. I do everything I can to prioritize and focus on the needs of women in particular.

Growing up with a single mother who worked hard and struggled also gave me the boldness to try to do basic income, because I told myself, “You’re taking a risk on people like your mom,” and that really kind of helped become my frame in terms of how I envisioned people would use the money.

And growing up with a father who’s been incarcerated has given me a special sensitivity to issues like criminal justice, and just how the impact of draconian incarceration policies have on families, children and communities. Now that I am a father myself, I actually empathize with my father a lot more and I recognize how difficult it has to be to be away from your children.

MarketWatch: In the documentary, we learned that you met the late civil-rights icon and Georgia congressman John Lewis in person when you were running for city council. How did the conversation go between the two of you? Is he someone you consider a mentor?

Tubbs: John Lewis was someone I really looked up to, and I continue to try to model myself after him. When I was running for city council, he came up to me and told me to “get in the way and make good trouble.”

Two people from the same movement [as Lewis] that I have deep relationships with who I consider more as mentors are Rev. James Lawson and [children’s rights activist] Marian Wright Edelman. I’ve known both since I was 19 years old, and they have been inspiration and guides in white spaces who have really pushed me to live the values I’ve found as an elected official.

MarketWatch: The racial wealth gap between Black and white Americans is substantial: The median wealth of white families was $188,200 at the end of 2019, while the median wealth of Black families was $24,100, according to the Federal Reserve. Do you think guaranteed basic income can help close the racial wealth gap and help reduce income inequality?

Tubbs: We do know that something as small as an income floor, even if given to everybody, will disproportionately help Black communities because they’re disproportionally in poverty or economically insecure.

Guaranteed income is a big first step to solving issues of income inequality involving issues of the racial wealth gap. But it’s income, not wealth, so we have to use income as a floor but then provide resources and opportunities for folks to really have an estate. But having the income, I think, allows people to have a foundation upon which they can begin to build wealth.

“ ‘If we can implicitly trust the wealthy with $2 trillion in free money, also known as tax cuts three years ago, we should be able to trust the rest of us with making the same decisions about what’s best for ourselves and our families.’ ”

MarketWatch: At what point do you think it might not be necessary to continue distributing guaranteed income payments? Is there a point where you think they could become ineffective?

Tubbs: The idea of the guaranteed income is for it to be part of our social contract. So in the same way [as] unemployment benefits and a lot of the other things we have, it would be ongoing and recurring. So the idea is that it’s part of what it means to American, and there will be no cutoff date for these opportunities for everyone to share in the wealth that’s creating our country.

MarketWatch: How come strings weren’t attached to the $500 monthly payments? Is it because you don’t want to impose value judgments on how people spend their money, or simply to observe what happens when strings aren’t attached?

Tubbs: [Government bailouts and tax incentives are] free money that we give to people with no strings attached. But usually those people are wealthy; usually those people are white people who are usually men, if you look at bailouts over the past 20 years. Every recession there’s a massive bailout given to corporations and CEOs with no strings attached, oftentimes after their bad behavior creates a recession we’re trying to solve.

Even in the COVID-19 crisis, we’ve just been giving free money — not to the American people, necessarily, but to titans of industry, corporations, businesses. That’s not hating on them, per se, but if we can implicitly trust the wealthy with $2 trillion in free money, also known as tax cuts three years ago, we should be able to trust the rest of us with making the same decisions about what’s best for ourselves and our families.

“ ‘If anything, a basic income will give people what Gene Sperling calls economic dignity — for the agency to actually have bargaining power about where they choose to work and what conditions they choose to work in.’ ”

[Editor’s note: Under the CARES Act passed in March, the federal government sent stimulus checks to lower- and middle-income Americans.]

MarketWatch: Like the $600 enhanced unemployment benefit jobless Americans were receiving from the CARES Act, universal and guaranteed basic income are seen by some as a disincentive to work. However, there’s evidence from prior basic income experiments that the payments don’t discourage people from working or seeking out employment opportunities. Are you finding that to be the case in Stockton?

Tubbs: A basic income probably doesn’t give an incentive to work because people are already working. The vast majority of people who can work in our country do work. If anything, a basic income will give people what Gene Sperling calls economic dignity — for the agency to actually have bargaining power about where they choose to work and what conditions they choose to work in.

One of the things that folks care about in terms of results will be if we capture how much we’re paying for poverty, because as the U.S. economy grows, not everyone has more money to spend. I think that’s the slam dunk.

MarketWatch: What, if anything, has surprised you about the economic impact of the experiment? Have you been able to change anyone’s perceptions when it comes to basic income? It seems to me that a great deal of people view it as handing out free money.

Tubbs: I was the most surprised at how something as small as $500 makes all the difference for a lot of people.

One story that I always highlight is of a man named Thomas. He said the $500 gave him enough of a cushion to take time off at his former job as an hourly retail worker, and he didn’t have paid time off to apply and interview for another job because he was never able to take that risk and lose a couple hundred dollars of work. But he was able to get a better-paying job with benefits and less hours. So that’s like the ultimate story about how something as small as $500 helps allow people to grow.

We have this insidious nature in our country of othering people as being fundamentally different from us in terms of values and the capacity to make good choices.

But if you instead pause and go, how would you spend the money? What could you do with $500? That creates a whole conversation, and that’s what we’ve done in Stockton.