This post was originally published on this site

As fears of a contested presidential election rise, investors are taking a look at how the market behaved during the closest precedent — the 2000 Florida recount battle between Democrat Al Gore and Republican George W. Bush.

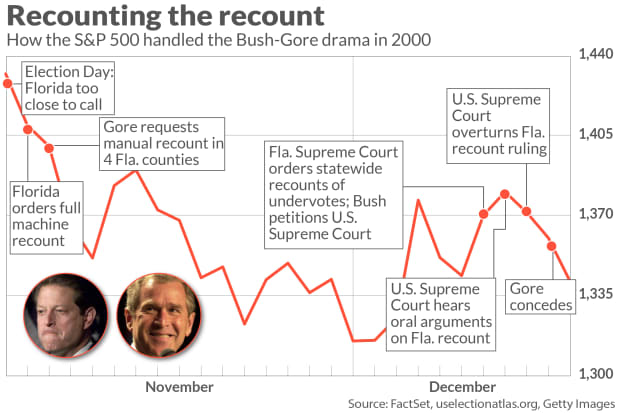

The chart above tracks the performance of the S&P 500 SPX, +0.84% from Election Day, which fell on Nov. 7, through Dec. 15. Over that period, the S&P 500 saw ups and downs, declining 8.4%.

2000 might not offer much of a road map, making it difficult to draw many conclusions about what a contested outcome following the Nov. 3 election pitting President Donald Trump against Democratic challenger Joe Biden would mean for the market. But activity in the options market, as reflected by the Cboe Volatility Index futures curve, shows how traders see the potential for an extended period of volatility beyond the election.

Read: As America votes, traders look to profit on the volatility

The 2000 contest wasn’t the first muddled presidential election result in U.S. history, but they’ve been rare. Three elections in the 19th century were decided by the House of Representatives or after congressional intervention.

But analysts worry that the potential for disputes in several states over mail-in ballots could make for a much more contentious environment than was the case in 2000.

“After all, we do have the most divisive and unknowable election (unclear, contested or both) of our lifetimes coming on 11/3,” said Julian Emanuel, strategist at BTIG, in a note earlier this week. “2000’s Bush v. Gore ‘Hanging Chads’ could look like Constitutional child’s play by comparison.”

Analysts at UBS noted last month that plaintiffs already filed 192 lawsuits in at least 41 states arising from changes to voting procedures in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Combined with other lawsuits that predate the coronavirus outbreak, the total number of challenges rises to more than 200.

The potential for trouble in the wake of this year’s election is drawing advance comparisons to 1876, when contested results in several states meant the election wasn’t decided until just before inauguration day, which was then in March.

Such worries weren’t soothed when Trump late Wednesday refused to commit to a peaceful transition of power following the election, telling reporters “we’ll have to see what happens…I’ve been complaining very strongly about the ballots. And the ballots are a disaster.” Trump was referring to mail-in ballots, which he has asserted, without evidence, are prone to widespread fraud.

Trump also suggested the Supreme Court would have to make a ruling on the outcome of the election, emphasizing that a new justice, replacing Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who died last week, should be confirmed before Election Day.

The battle over a Supreme Court nominee already was seen all but eliminating prospects for an agreement between congressional Democrats and the White House on an additional round of spending aimed at shoring up the economy as it attempts to rebound from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Stocks were flipping between gains and losses Thursday, with the S&P 500 up 0.8% a day after finishing just shy of correction territory, defined as a pullback of 10% from a recent peak. The Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, +0.75% was trading up 0.7%.