This post was originally published on this site

Home for sale in San Francisco, California.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Wall Street’s foray back into lending to homeowners with spotty credit isn’t looking great during the coronavirus pandemic.

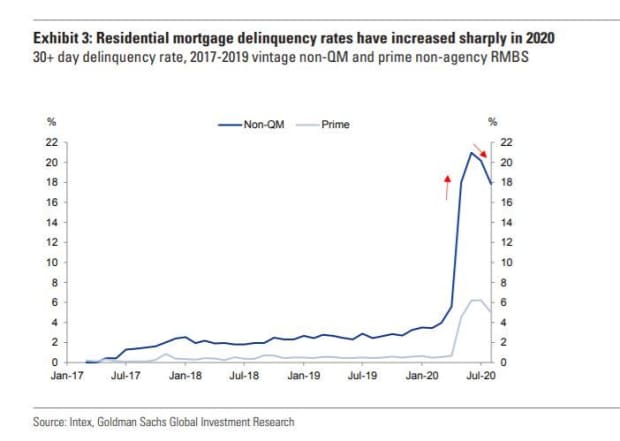

It’s still early days, but delinquencies on residential mortgages bundled into private bond deals, or without government backing, have shot up to about 18% as of July from a low of about 4% in January, according to Goldman Sachs.

Wall Street home loans

Goldman Sachs

That’s a dip from a recent high of more than 20%.

The Goldman chart breaks out the performance of loans in “non-QM” bond deals from those pegged as “prime,” a category that unsurprisingly has reported far lower delinquencies of 30-days or more.

Prime borrowers typically have credit scores of 670 or higher, with those in the subprime category closer to an 580 to 669 range, according to Experian, a credit reporting bureau.

In Wall Street parlance, “non-QM” is a category of home loan that doesn’t fit within the government’s “Qualified Mortgage” standard, which was put in place as part of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 to help ensure most new home loans wouldn’t include risky features and also would be easier for borrowers to understand.

Goldman analysts said they still expect U.S. home price growth to rise 4.2% this year and 2.6% in 2021. “However, while housing market prospects appear favorable, the outlook for residential credit exposure remains somewhat cloudy,” wrote a team led by Marty Young in a weekly note.

U.S. benchmark stock indexes were heading lower for a third session Friday, after the Federal Reserve on Wednesday indicated it likely will be a long road to economic recovery due to the pandemic, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, -0.83% down about 1.2% in afternoon trade.

Fed Chairman Powell has repeatedly stressed that the central bank’s powers remain limited in terms of providing aid to hard-hit and lower income borrowers due to Covid-19, including Blacks and Hispanics who are already suffering from income equality. He has suggested several times during the pandemic that Congress should consider doing more to help shore up borrowers and aid the economic recovery.

Overall, private mortgage bond issuance remains only a fraction of the of the overall $11.2 trillion U.S. housing debt market, according to the Urban Institute, which notes that federally backed home loans still dominate. Many of those loans now also qualify for sweeping, pandemic forbearance relief.

So far this year, some $58.4 billion worth of private residential mortgage bonds have been issued, of which 20% were categorized as Non-QM, according to Deutsche Bank data.

JP Morgan Chase & Co. JPM, -0.19% and Wells Fargo WFC, -0.41% have been the top bank issuers of residential mortgage bonds this year, according to Finsight, a platform that tracks bond issuance.

Once big banks put crisis-era fines and regulatory probes in the rearview mirror, they began ramping up their own lending to borrowers that fall outside of the QM or government lending standards.

The Trump administration, as part of its promise to deregulate Wall Street, in August proposed rolling back parts of the mortgage lending standard.

Wall Street banks were at the center of the last decade’s subprime lending boom in U.S. housing and the 2007-’08 global financial crisis, which resulted in an estimated 10 million borrowers losing their homes to foreclosure and billions of dollars worth of fines paid out by big banks that packaged trillions of dollars of residential loans into private bond deals.

After the 2008 crash, that business dried up, except for a bustling corner of the market where private lenders were bundling up older home loans with a checkered performance history into new residential mortgage bond deals to sell to investors.

Several real-estate investment trusts, including Redwood Trust RWT, -0.12%, started also started making prime “jumbo” mortgages, or high balance loans in expensive property markets, particularly in places like New York City and the San Francisco Bay Area, to bundle into private mortgage bond deals.

But they also faced lower-cost competition from housing giants Freddie Mac FMCC, +2.10% and Fannie Mae FNMA, +2.26%, which have increased how much can be borrowed against a home, but still qualify for a federal financing. For example, the agency’s loan maximum reached $765,600 this year for a single-family home in high-cost areas .

Performance of home loans to prime borrowers has been less of a concern than borrowers with thin credit files, lower credit scores or blemished credit histories.

“We expect most of the prime borrowers who have entered into forbearance programs to ultimately reperform, but data justifying

this expectation are admittedly so-far fairly limited,” the Goldman team wrote.