This post was originally published on this site

https://images.mktw.net/im-48070866The release of the Federal Reserve’s undefined (SCF) offers an opportunity to reassess Americans’ retirement preparedness as measured by the National Retirement Risk Index (NRRI).

The NRRI estimates the share of American households that are at risk of being unable to maintain their preretirement standard of living in retirement.

Constructing the NRRI involves three steps:

1) projecting a replacement rate — retirement income as a share of preretirement income — for a nationally representative sample of working-age households;

2) constructing a target replacement rate consistent with maintaining a preretirement standard of living in retirement;

3) comparing the projected and target replacement rates to find the percentage of households “at risk.”

Since the last SCF was conducted in 2019, the nation experienced a global pandemic and economic disruption, and 2022 was a very bad year for stock and bond returns. These factors would have reduced households’ retirement preparedness. At the same time, the government provided unprecedented fiscal support, employment remained strong, home values rose substantially, and the stock market — even with the drop in 2022 — ended up significantly higher than in 2019.

The 2022 NRRI shows that the gains in asset values more than offset the economic disruption to produce the lowest level of households at risk since the NRRI first started. Specifically, between 2019 and 2022, the share at risk dropped from 47% to 39% (see Figure 1).

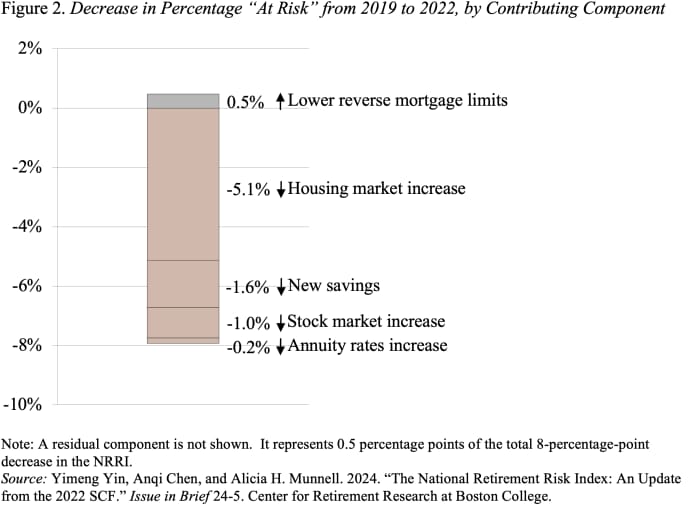

Figure two breaks down the reasons for the big reduction in the NRRI. The increase in home prices leads the list, followed by new savings during the pandemic, and stock market gains. Rising interest rates had small offsetting effects by reducing how much home equity that households can tap through reverse mortgages.

What do the 2022 results imply for the future? Two major contributors to the stunning improvement in the NRRI seem unlikely to persist.

First, housing prices are about 14% above their long-run trend for the last 30 years, and may well revert to trend over time.

Second, “new saving” is almost certainly a one-shot COVID phenomenon. Indeed, personal saving rates have returned to prepandemic levels and so has credit card borrowing. Thus, the spectacular decline in the share of households at risk may not hold for the future.

But assume the good news is permanent, and future NRRIs hover around 40%. That finding means about two-fifths of today’s working-age households will not have enough retirement income to maintain their preretirement standard of living. This analysis continues to confirm that we need to fix our retirement system so that Social Security is financially sound and employer plan coverage is universal.