This post was originally published on this site

https://images.mktw.net/im-47053612

At age 80, Sly Stone has written a memoir. The musician reflects on his ups and downs with brutal honesty, recalling his early fame, drug abuse, arrests and failed comeback attempts.

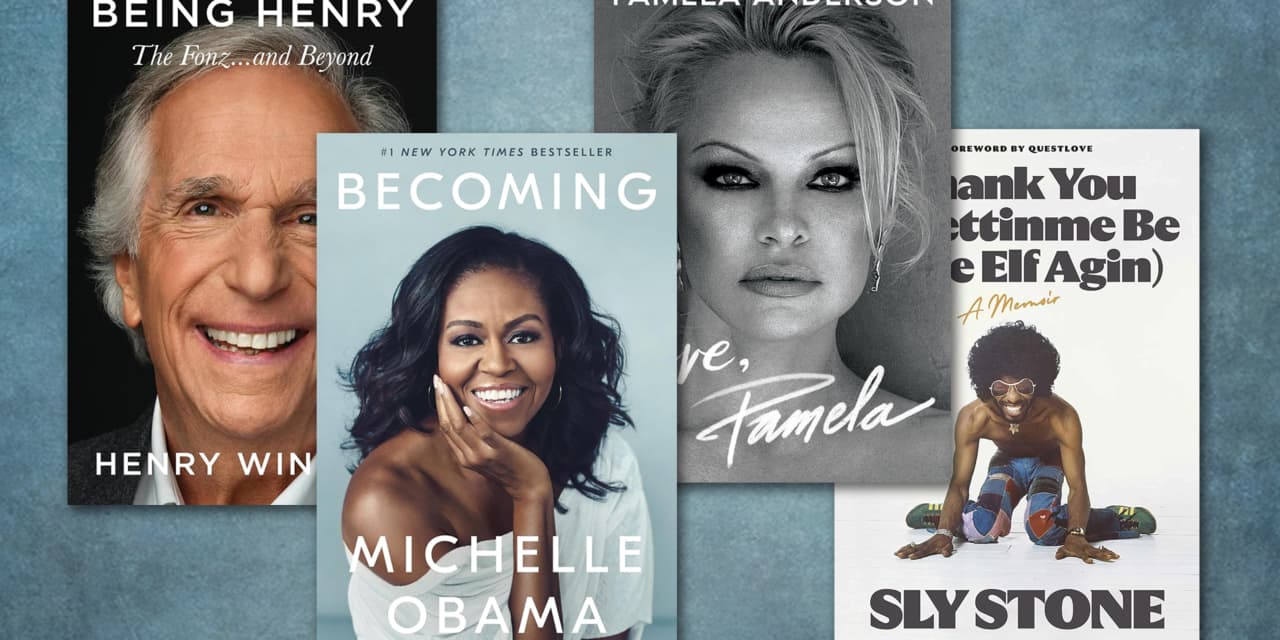

Celebrity memoirs are nothing new. Their often-harrowing content can offer cautionary tales while educating and inspiring readers. Last year, we saw a flood of celebrity memoirs published, including by Stone, Jada Pinkett Smith, Patrick Stewart, Dolly Parton and Kerry Washington.

What’s new is how many non-famous retirees are writing memoirs. Eager to document their life and enrich their legacy, they reflect on how they lived, whom they loved and what they’ve learned.

It helps if you’ve laid the groundwork. That’s better than waking up one day and declaring, “I’m going to write 270 pages about my life.”

If you’ve kept a journal for years or filled a file with occasional musings, colorful anecdotes and newspaper clippings, you already have a head start.

“I started parts of my memoir years ago,” said Denis Ledoux, 77, a writing coach who specializes in memoirs. “Only in the last two or three years did I get serious about it.” His memoir, titled “French Boy: A 1950s Franco-American Childhood,” was independently published in October.

The key to memoir writing is to proceed in stages, Ledoux says: Rather than start from scratch after you retire, pave the way by telling one story at a time throughout your life.

“Think of your memoir as an anthology of stories,” said Ledoux, who lives in Lisbon Falls, Maine. “The stories can be about a seminal experience, a relationship you had or any other specific memory.”

To shape your narrative, choose a central theme. This guides your organizational structure and lends purpose to every page.

“I wanted my memoir to make a statement about my background,” Ledoux said. “Writing it was therapeutic and helped me come to an understanding and acceptance of hard events.”

Even if you’ve assembled years of stories as a starting point for your memoir, the process of integrating the stories into a coherent whole takes lots of effort. Muster your discipline to stick with it and finish the job.

To make progress, set aside time each day to write. Even if you commit to just 30 minutes per day, keep it up.

“Once you get in the habit, it’s very nurturing,” Ledoux said. “Otherwise, people might give up or think, ‘I don’t have time to do this.’”

If you’re not accustomed to writing, consider joining a writers group. See if your local library, university or adult education center offers such a program.

Read: Why cassette tapes are making a comeback — and it’s not just a fad

After retiring as a theater professor at Wright State University, Abe Bassett joined a writers group led by a colleague. This led him to collect dozens of stories, which he then categorized under various headings (growing up with Dad, a stint in the Army, etc.).

“The best stories reveal something about the writer,” said Bassett, 93, author of “Abe, Son of Abraham.” “The stories have to be on point and interesting” — not just to you, but also to readers.

Like Ledoux and Bassett, Dorothy Lazard relied on a patchwork of written stories as the basis for her 2023 memoir, “What You Don’t Know Will Make a Whole New World.”

“I wrote it all along about key moments in my life,” Lazard said. “I’ve been journaling since I was a kid.”

Eager to mark 50 years of living in California, she wrote her memoir to trace her experiences and how they empowered her to grow and gain wisdom.

Like many memoir writers, Lazard came to realize that reaching a wider audience took a leap of faith.

“I saw I was writing for someone else, not just for myself to satisfy a private need,” she said. “That can be stultifying. Knowing it will be looked at by strangers can be really difficult. It can cause external pressures and external judgment” that can lead you to self-censor your work.

Lazard, 64, overcame this challenge by heeding memoirist Tobias Wolff’s observation that memory has its own story to tell.

“I wanted to tell stories that clung to me,” she said. “I tell people, ‘This is a story my memory had to tell.’”

If you’re thinking of revealing intimate details about family and friends, Lazard says, you should prepare to be asked, “What did they think of what you wrote?”

As a precaution, you can invite them to review your manuscript and give feedback. But think twice before you bend over backward to accommodate them.

“Don’t compromise your voice by telling a story from someone else’s perspective,” Lazard said. “Be committed to the story you want to tell.”