This post was originally published on this site

https://images.mktw.net/im-46587397

In a year like 2023, when the S&P 500

SPX

was up about 23% and corporate bond funds had total returns of 8% or so, it’s been easy to be a bull-market genius. But since many years aren’t so terrific (looking at you, 2022), you may want to read books to make you smarter about investing, especially managing your portfolio in retirement.

Figuring out how to invest your retirement portfolio wisely can be challenging when leaving a full-time job. As the three scholars who wrote the Financial Services Review paper “The Pros and Cons of Remaining in a 401(k) Plan After Retirement” said, most 401(k) participants “are likely to lack the skills to do a good job constructing their own portfolios without advice.”

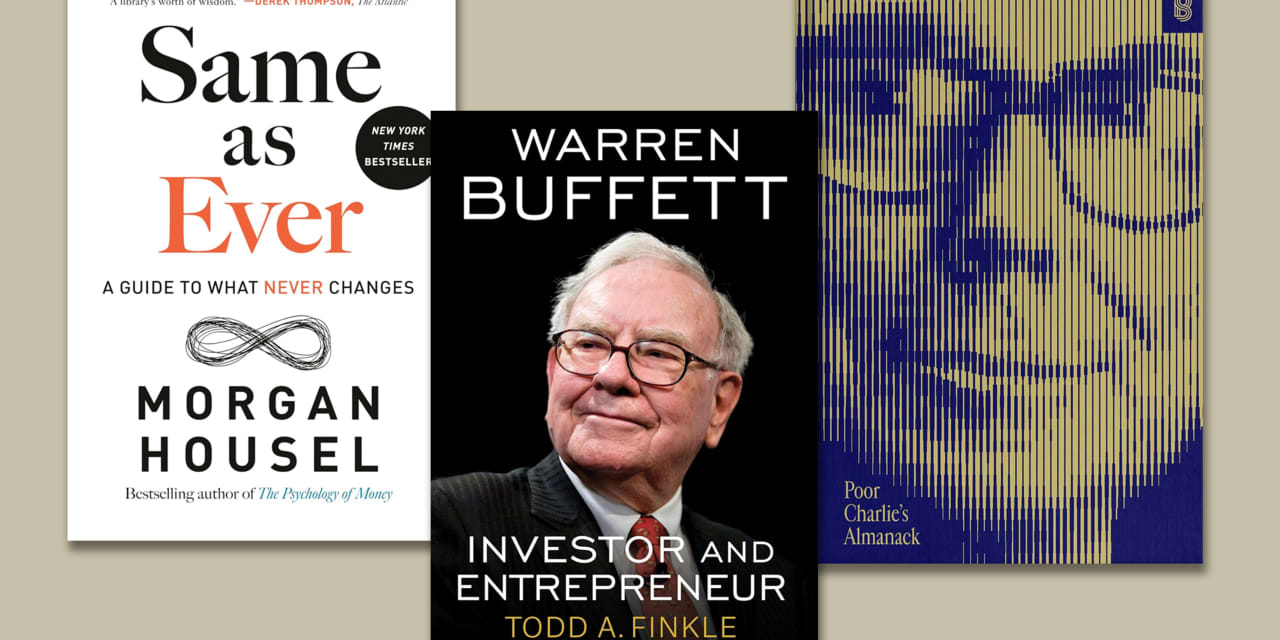

I’d like to recommend three helpful new books that have a common principle: Invest for the long term.

Two focus on the stock-market strategies of a remarkable value-investing duo: billionaires Warren Buffett and the recently departed Charlie Munger. They’re “Warren Buffett: Investor and Entrepreneur,” by Gonzaga University entrepreneurship professor and investor Todd A. Finkle, and “Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Essential Wit & Wisdom of Charles T. Munger,” edited by Peter D. Kaufman.

The third is a provocative look into the psychology of investing and personal finance, “Same as Ever: A Guide to What Never Changes” by Morgan Housel, a partner at the Collaborative Fund and author of the best-selling “The Psychology of Money.”

‘Warren Buffett: Investor and Entrepreneur’

You may think you know plenty about Buffett, the CEO and chair of Berkshire Hathaway

BRK.A,

BRK.B,

But Finkle’s new book will show you how the Oracle from Omaha implemented his successful buy-and-hold strategy and what you can learn from it. (Particularly useful: chapters 5, “Berkshire’s Investment Methodology,” and 7, “How to Make Better Investment Decisions.”)

Finkle sprinkles in Buffett’s life story, whom he learned from, how his investing style evolved, mistakes he made and why his partnership with fellow Omaha native Munger has been vital to the performance of their stock and company.

The author describes how Buffett learned early the importance of investing patiently. He bought three shares of Cities Service (now CITGO) at age 11, paying $38.25 a share and then selling them for $40, only to see the price rise to $200.

At 19, Buffett read, and became a devoted fan of, Benjamin Graham’s “The Intelligent Investor” and its strategy of buying bad companies at great prices.

Finkle writes that Buffett often says the three most important words for investing are Graham’s: margin of safety, or the difference between a stock’s price and the investor’s estimation of its intrinsic value. A large margin of safety provides a cushion against errors.

Buffett was later taken by the book Graham co-wrote with Philip A. Fisher, “Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits and Other Writings,” altering his investing technique in ways you might want to emulate.

Fisher used the “scuttlebutt methodology” — gathering knowledge about a business through personal experience — and believed in buying great companies at good prices, then holding onto them. As Finkle reports Buffett saying at his 2008 shareholder meeting: “I have no idea what the stock market is going to do. … I am looking for the stock to go down so I can buy it on sale.”

Read: This one insight can transform your 401(k) — and it’s hiding in plain sight

‘Poor Charlie’s Almanack’

For decades, Berkshire Hathaway Vice Chairman Charlie Munger was largely known as Buffett’s sidekick and the jokester at their annual Berkshire Hathaway shareholder extravaganza — er, meeting. But after his death last month at 99, Munger has been receiving his due as a brilliant investor.

In a new, abridged edition of “Poor Charlie’s Almanack” (a joking reference to “Poor Richard’s Almanack” by Munger’s idol Ben Franklin), Peter D. Kaufman publishes 11 of his longtime friend and associate’s famous, often funny, talks about investing, life and decision-making.

Its most helpful parts are chapter 3’s sections on Munger’s investment evaluation process and the nine principles of his investment checklist. A vital consideration for Munger (and Buffett) before investing: A company needed a competitive advantage that Munger called its “moat.”

Kaufman also slides in Munger’s personal story — he was a successful real-estate lawyer and investment partner initially — and the backstory of his friendship and business relationship with Buffett. Kaufman quotes Buffett saying: “Charlie can analyze and evaluate any kind of deal faster and more accurately than any man alive. He sees any valid weakness in 60 seconds. He is a perfect partner.”

One way Munger could detect a deal’s weakness or a stock’s potential so well: He was a brilliant student of psychology. As Kaufman writes: “Charlie conducts a comprehensive analysis of both the internal workings of the investment candidate as well as the larger, integrated eco-system in which it operates,” using roughly 100 tools Munger called his “mental models.”

They borrowed from not just psychology, but also history, physiology, mathematics, engineering, biology, physics, chemistry, statistics and economics. Munger’s goal: finding a stock that would provide “lollapalooza” results.

There was a lot going on behind Munger’s jokes.

‘Same as Ever’

I liked Morgan Housel’s first book, “The Psychology of Money,” so much that I gave it to my two adult sons to read after finishing it. I’ll likely do that with “Same as Ever,” too.

Housel, an expert on behavioral finance and history, is a young, gifted writer and a two-time winner of the Best in Business Award from the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, formerly the Society of American Business Editors and Writers. He was a contributor to the Wall Street Journal and a columnist for the Motley Fool before becoming a partner at the Collaborative Fund, a venture-capital firm for tech companies.

Like Malcolm Gladwell, Housel often takes a counterintuitive approach to things. In “Same as Ever,” his thesis is that investors are better off studying what hasn’t changed over the years and how to profit from it, rather than how the future might change.

The biggest risk of the next 10 years, Housel writes, will be something nobody is talking about today. “Change captures our attention because it’s surprising and exciting,” he says. “But the behaviors that never change are history’s most powerful lessons.”

Echoing Buffett, who advised investors to be greedy when others are fearful, Housel goes on to say, “I have no clue what the stock market will do next year (or any year). But I’m very confident about people’s penchant for greed and fear, which never changes. So that’s what I spend my time thinking about.”

Investors, he maintains, would do better to have expectations that risk will arrive, even if they don’t know when or where, rather than relying on forecasts about them.

For savers, Housel advises: “The right amount of savings is when it feels like it’s a little too much. It should feel excessive; it should make you wince a little.”

Housel’s mantra is to save like a pessimist and invest like an optimist.

Like Buffett and Munger, he takes a long-term approach to investing and recommends the rest of us do, too.

He cites history to make a convincing argument, with a compelling chart of the percentage of periods when stocks earned a positive return between 1871 and 2018, adjusted for dividends and inflation. Housel’s results for one day; two, three, four, five and nine months; and one, two, four, five, 10, 15, 20 and 30 years, reveal positive returns at least 52% of the time in each period and over 75% of the time for the two- to 30-year periods.

The “most convenient” investing time horizon, when markets nearly always reward your patience, Housel concludes, is probably around 10 years or more.

The key question for investors is not “How can I earn the highest returns?” Housel writes. It’s “What are the best returns I can sustain for the longest period of time?”

As he notes: “Little changes compounded for a long time create extraordinary changes. Same as ever.”