This post was originally published on this site

https://images.mktw.net/im-90829871Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell in the past week gave investors “chilling” in short-term Treasury bills a reason to consider pivoting to something else.

Yields on 3-month

BX:TMUBMUSD03M

and 6-month

BX:TMUBMUSD06M

Treasury bills have been seeing yields north of 5% since March when Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse ignited fears of a broader instability in the U.S. banking sector from rapid-fire Fed rate hikes.

Six months later, the Fed, in its final meeting of the year, opted to keep its policy rate unchanged at 5.25% to 5.5%, a 22-year high, but Powell also finally signaled that enough was likely enough, and that a policy pivot to interest rate cuts was likely next year.

Importantly, the central bank chair also said he doesn’t want to make the mistake of keeping borrowing costs too high for too long. Powell’s comments helped lift the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA

above 37,000 for the first time ever on Wednesday, while the blue-chip index on Friday scored a third record close in a row.

“People were really shocked by Powell’s comments,” said Robert Tipp, chief investment strategist, at PGIM Fixed Income. Rather than dampen rate-cut exuberance building in markets, Powell instead opened the door to rate cuts by midyear, he said.

New York Fed President John Williams on Friday tried to temper speculation about rate cuts, but as Tipp argued, Williams also affirmed the central bank’s new “dot plot” reflecting a path to lower rates.

“Eventually, you end up with a lower fed-funds rate,” Tipp said in an interview. The risk is that cuts come suddenly, and can erase 5% yields on T-bills, money-market funds and other “cash-like” investments in the blink of an eye.

Swift pace of Fed cuts

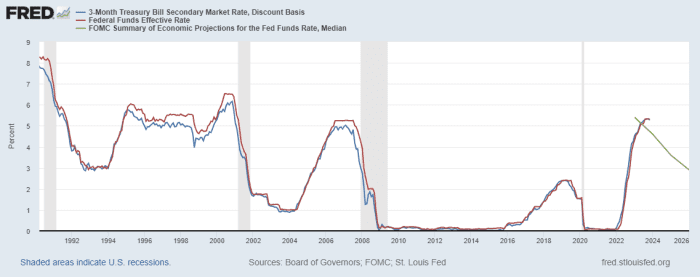

When the Fed cut rates in the past 30 years it has been swift about it, often bringing them down quickly.

Fed rate-cutting cycles since the ’90s trace the sharp pullback also seen in 3-month T-bill rates, as shown below. They fell to about 1% from 6.5% after the early 2000 dot-com stock bust. They also dropped to almost zero from 5% in the teeth of the global financial crisis in 2008, and raced back down to a bottom during the COVID crisis in 2020.

Rates on 3-month Treasury bills dropped suddenly in past Fed rate-cutting cycles

FRED data

“I don’t think we are moving, in any way, back to a zero interest-rate world,” said Tim Horan, chief investment officer fixed income at Chilton Trust. “We are going to still be in a world where real interest rates matter.”

Burt Horan also said the market has reacted to Powell’s pivot signal by “partying on,” pointing to stocks that were back to record territory and benchmark 10-year Treasury yield’s

BX:TMUBMUSD10Y

that has dropped from a 5% peak in October to 3.927% Friday, the lowest yield in about five months.

“The question now, in my mind,” Horan said, is how does the Fed orchestrate a pivot to rate cuts if financial conditions continue to loosen meanwhile.

“When they begin, the are going to continue with rate cuts,” said Horan, a former Fed staffer. With that, he expects the Fed to remain very cautious before pulling the trigger on the first cut of the cycle.

“What we are witnessing,” he said, “is a repositioning for that.”

Pivoting on the pivot

The most recent data for money-market funds shows a shift, even if temporary, out of “cash-like” assets.

The rush into money-market funds, which continued to attract record levels of assets this year after the failure of Silicon Valley Bank, fell in the past week by about $11.6 billion to roughly $5.9 trillion through Dec. 13, according to the Investment Company Institute.

Investors also pulled about $2.6 billion out of short and intermediate government and Treasury fixed income exchange-traded funds in the past week, according to the latest LSEG Lipper data.

Tipp at PGIM Fixed Income said he expects to see another “ping pong” year in long-term yields, akin to the volatility of 2023, with the 10-year yield likely to hinge on economic data, and what it means for the Fed as it works on the last leg of getting inflation down to its 2% annual target.

“The big driver in bonds is going to be the yield,” Tipp said. “If you are extending duration in bonds, you have a lot more assurance of earning an income stream over people who stay in cash.”

Molly McGown, U.S. rates strategist at TD Securities, said that economic data will continue to be a driving force in signaling if the Fed’s first rate cut of this cycle happens sooner or later.

With that backdrop, she expects next Friday’s reading of the personal-consumption expenditures price index, or PCE, for November to be a focus for markets, especially with Wall Street likely to be more sparsely staffed in the final week before the Christmas holiday.

The PCE is the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, and it eased to a 3% annual rate in October from 3.4% a month before, but still sits above the Fed’s 2% annual target.

“Our view is that the Fed will hold rates at these levels in first half of 2024, before starting cutting rates in second half and 2025,” said Sid Vaidya, U.S. Wealth Chief Investment Strategist at TD Wealth.

U.S. housing data due on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday of next week also will be a focus for investors, particularly with 30-year fixed mortgage rate falling below 7% for the first time since August.

The major U.S. stock indexes logged a seventh straight week of gains. The Dow advanced 2.9% for the week, while the S&P 500

SPX

gained 2.5%, ending 1.6% away from its Jan. 3, 2022 record close, according to Dow Jones Market Data.

The Nasdaq Composite Index

COMP

advanced 2.9% for the week and the small-cap Russell 2000 index

RUT

outperformed, gaining 5.6% for the week.

Read: Russell 2000 on pace for best month versus S&P 500 in nearly 3 years

Year Ahead: The VIX says stocks are ‘reliably in a bull market’ heading into 2024. Here’s how to read it.