This post was originally published on this site

The Russia-Ukraine war is approaching its second year, and the ultimate cost of the conflict has been borne by innocent Ukrainians whose lives have been ended or upended by the Russian invasion.

U.S. taxpayers have also paid a price, however, with total U.S. aid, both military and humanitarian, allocated to the conflict now totaling more than $111 billion, the White House says.

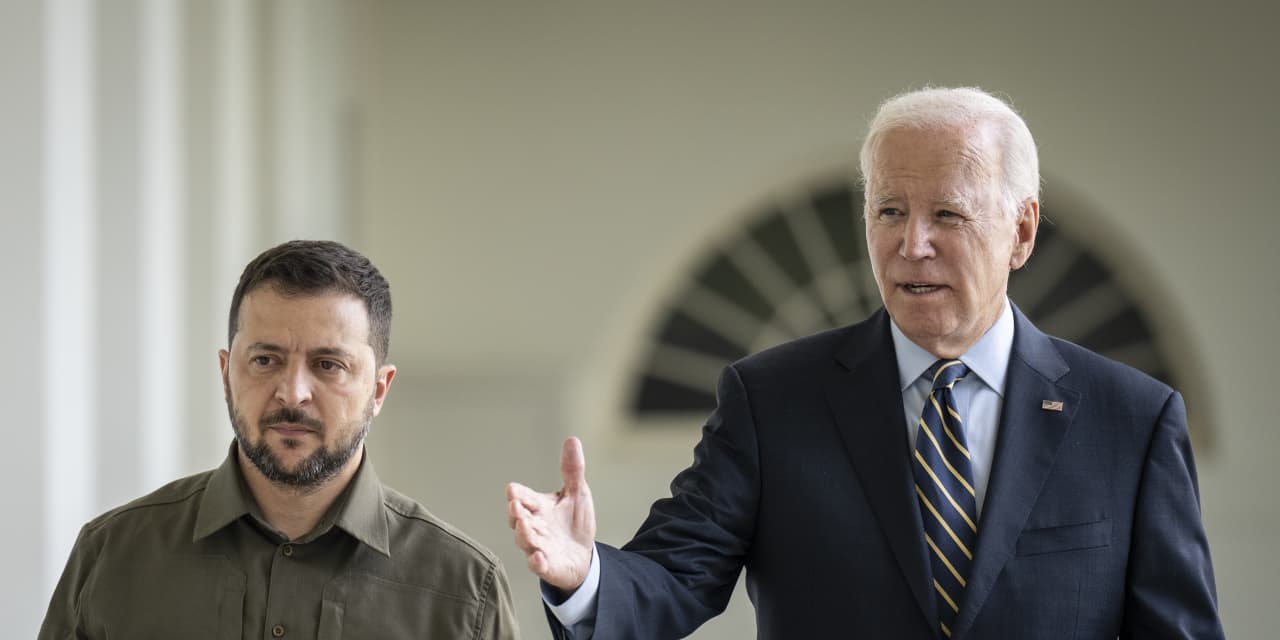

President Joe Biden has also asked Congress for an extra $61 billion, which the White House described in a letter to House Speaker Mike Johnson on Monday as urgently needed.

Without the new money “we’ll run out of resources to procure more weapons and equipment for Ukraine” by the end of the year, wrote Shalanda Young, director of the Office of Management and Budget.

“There is no magical pot of funding available to meet this moment,” she added. “We are out of money — and nearly out of time.”

If Congress accedes to the request, it would bring the total cost of aid near to the cost of programs dear to the president and his party which would arguably benefit the average American more than defending Ukraine’s territorial integrity.

Take for instance, the expanded child tax credit that Democrats passed through the American Rescue Plan shortly after Biden took office. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that making that plan permanent would cost about $105 billion per year, roughly in line with the cost of the Ukraine war on a proportional basis.

A recent AP-NORC poll shows a plurality of Americans think the U.S. is spending too much in Ukraine, with one respondent telling the news service: “I understand the U.S. has been an ally to others, but I feel like, let’s take care of our people first.”

Why is new funding for Ukraine is so urgent?

Given waning support for the war among the American public, it’s no surprise a vocal contingent in the Republican Party has begun questioning whether new aid is needed.

But congressional leadership of both parties has said new aid is a priority, and their awareness of the geopolitical stakes of the conflict likely explains why, according to Max Bergmann, director of the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Europe, Russia and Eurasia Program.

“The impact of failing to pass new funding would be devastating for Ukraine, and it would have very tangible impacts not just on the battlefield but for Ukrainian citizens,” he said. “If Ukraine doesn’t get new munitions, they are essentially going to have to let Ukrainian cities get bombarded because they’ll need to ration what they have to protect ground forces.”

Funding for Ukraine ran out Oct. 1, he said, and since that date, the U.S. has been dolling out less and less aid each month as the Defense Department scrounges for munitions that current law enables it to send for the effort.

The Russians, meanwhile, have been ramping up production of long-range cruise missiles that they can use to “pummel Ukrainian cities” unless Ukraine can get more air defense munitions from the U.S., which have been effective at protecting civilian life, Bergman added.

“Cutting off the flow of U.S. weapons and equipment will kneecap Ukraine on the battlefield, not only putting at risk the gains Ukraine has made, but increasing the likelihood of Russian military victories,” OMB Director Young wrote in her Monday letter.

What has the U.S. already given Ukraine?

Not all of the $111 billion spent on the war has gone directly to Ukraine — CSIS reports for instance that $421 million has been spent on U.S. military services and for salaries for troops sent to NATO allies in Europe.

The State Department and the United States Agency for International Development have also been allocated billions of dollars for economic assistance to the region, migration and refugee assistance and similar programs.

The Office of Management and Budget told MarketWatch that direct military assistance to Ukraine has so far totaled $44 billion, broken down into two categories: the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative and the Presidential Drawdown Authority, which allows the president to grant munitions from already existing stockpiles of weapons.

Advocates for the PDA funding program say that it actually bolsters the U.S. military’s readiness, because the appropriated funds enable stockpiles to be replenished with the most modern versions of American-made munitions.

Another $3.3 billion has been allocated to investments “in U.S. industrial base infrastructure to expand domestic capacity and increase production of critical munitions and materiel for Ukraine,” according to Pentagon spokesperson Maj. Charlie Dietz.

Impact on the U.S. economy

The Pentagon also points out the stimulative impact of the war spending on the U.S. economy and American jobs. An analysis by former Marine Corps Col. Mark Cancian found that almost $68 billion of the $111 billion so far allocated is spent in the United States, supporting jobs in the U.S. defense industry.

Clara Keuss, Noah Burke and Marc Thiessen of the American Enterprise Institute published research last week showing that workers in at least 31 states are producing weapons systems for Ukraine, not counting the suppliers of tools needed to build those systems.

“Our military aid to Ukraine is revitalizing manufacturing communities across the United States, creating good jobs here at home and restoring the United States’ capacity to produce weapons for our national defense,” Thiessen wrote. “Helping Ukraine is the right thing to do for U.S. national security. It is also the right thing to do for American workers.”

The funding has also boosted the stock prices of companies involved in defense production, as tracked by the SPDR S&P Aerospace & Defense ETF

XAR

Read more: This defense ETF’s rally suggests more U.S. funding for Ukraine will come through

What’s the endgame?

Even granting that Ukraine urgently needs military aid to continue to repel the Russian invasion and protect its civilians, it’s unlikely that Congress can sustain support for the effort at the pace it has for the first 21 months of the conflict.

Even those in the growing chorus of voices calling for the U.S. to seek a negotiated settlement to the war may see the logic in continuing to supply Ukraine with weapons, perhaps at a reduced rate, and committing to do so in the future.

Benjamin Friedman, policy director at Defense Priorities and a critic of U.S. policy toward Ukraine, told MarketWatch he believes the White House “should be looking for ways to end the war, and that means convincing Ukraine that it’s not going to get all its territory back.”

That doesn’t mean he is for cutting off aid altogether, because the promise of continued assistance strengthens Ukraine’s hand in negotiation.

“I would try to make a virtue out of the political uncertainty out of the aid,” he said, arguing that it would strengthen the hand of political forces in the Ukrainian government that want to push for a cease fire.

“It doesn’t mean I’m cutting you off, but it does mean that you should start to expect less and plan accordingly,” he added. “The idea would be you would get Ukraine’s politics moving in the right direction.”