This post was originally published on this site

“ ‘Entrepreneur’ is a French word, but it by no means applies to the kind of people who are getting very rich in France today. ”

People seldom think of Paris as an industrial city. There is too much about France’s capital that is focused on love and leisure: wispy dreams evoke romantic walks along the Seine quay, restaurants where you can woo a partner all night over endless courses, and a generally timeless atmosphere that defines the expression joie de vivre. Not much time for boring work, in other words, let alone actually making the money necessary to enjoy a chilled Gallic lifestyle.

Greater Paris is by far France’s biggest economic hub, but it has none of the workaday tension of a Chicago, Houston or New York. American workers used to minimalist vacations and hurried sandwiches between meetings would be shocked at the relaxed labor conventions that France retains. For many, they include taking the whole of July or August off, and insisting on a sit-down brasserie lunch with all their colleagues at least once a week.

Despite this, two Parisians now top the world’s richest lists. One is Bernard Arnault, who as of late September 2023 was worth about $183 billion, according to Forbes, making him the world’s wealthiest person after Tesla’s Elon Musk, and the wealthiest person in France. The other is Françoise Bettencourt Meyers, whose fortune Forbes values at more than $82 billion, making her the richest woman in both France and the world.

Arnault is the boss of the luxury goods conglomerate Moët-Hennessy Louis Vuitton, or LVMH

MC,

as it is usually referred to. His place of work is the riverside office block by his group’s flagship hotel in the city, the Cheval Blanc (White Horse), next to the Pont-Neuf, the oldest bridge in Paris.

Even at the age of 74, Arnault puts in 12-hour days. Security is understandably very important to him — LVMH HQ is surrounded by bodyguards with earpieces — but he could technically stroll to his desk from his nearby mansion, one that is full of postmodernist paintings, Louis XVI furniture and books dating back to the Middle Ages. It really is hard to think of a more Parisian businessman than Arnault.

Bettencourt Meyers, 70, is heiress to the L’Oréal empire and Arnault’s female equivalent. She was born in Neuilly-sur-Seine, the western Paris suburb, close to where L’Oréal

OR,

LRLCY,

is based. Bettencourt Meyers still lives in Neuilly and maintains a strong loyalty to her home city. For example, after Notre Dame Cathedral was ravaged by fire in 2019, she pledged some $226 million to repair it.

Beyond their global status, being the richest man and woman in France comes with a lot of local publicity. The pair are treated like heads of state, with their reputations exposed like never before.

Except that this is not necessarily a positive development. On the contrary, you often hear Arnault’s name chanted disparagingly at the mass anti-government protests regularly held across France –vthe sort that frequently degenerate into riots. Arnault is not necessarily viewed as the type of wealth-creating innovator that is normally lauded in America. “Entrepreneur” is a French word, but it by no means applies to the kind of people who are getting very rich in France today.

“ Neither LVMH nor L’Oreal provides an entreprenuerial model that might translate to ordinary people. ”

Instead, both LVMH and L’Oréal trade in highly conservative products, with profits ultimately the result of the fine-tuning of inherited companies that have been successful for generations. LVMH is essentially a conglomerate of all the products that historically made France great — from Champagne to fashion houses such as Christian Dior. The LVMH umbrella now covers iconic foreign success stories too, including U.S. jeweler Tiffany & Co., which was founded in New York in 1837, and Swiss watchmaker TAG Heuer, which goes back to 1860.

L’Oréal has been making beauty products since the early 20th century. It now owns close to 40 cosmetics brands and has expanded across the globe, while keeping the descendants of its founder, Eugène Schueller, in enormous wealth.

The problem is that neither of these great multinationals provides a model that might translate to ordinary people. On the contrary, LVMH staff tend to sell products they will never be able to afford themselves (this is a complaint often raised by trade union-led strikers at Arnault’s stores). Many of the new businesses that receive government support in France don’t extend far beyond selling small-scale Brittany pottery and the like. Much of it is low key and has no hope of generating the kind of income that, say, a Silicon Valley equivalent will amass.

PublicAffairs

Rich-list topping American multi-billionaires, such as Microsoft founder Bill Gates, might have come from comfortable backgrounds, but they still take enormous risks and create products that are astonishingly innovative. This fits in with the ruggedly individualistic nature of American capitalism, compared to the bourgeois version on offer in France (“bourgeois” — which denotes a lifestyle influenced by private property interest — is an apt French word heard far more than entrepreneur in modern France).

Despite the meritocratic ideals championed in Republican France, up-and-coming members of the Arnault and Bettencourt dynasties will certainly earn a lot more creaming off profits on family capital, rather than trying to build up their own reputations as dynamic game changers. This French emphasis on exploiting mature cash machines guarantees low economic growth, as well as vast inequality in a land where the minimum wage in 2023 is €11.52 an hour, the equivalent of just over U.S.$12.

Multinationals such as L’Oréal and LVMH export capitalism brilliantly, but conditions for doing good business in France can be a lot more restrictive. It costs a lot of money to hire staff, and there is little encouragement to business-minded people who want to break out of housing estates or isolated rural areas.

In short, the entire French business sector is dominated by the previously wealthy, with promising projects led by those who have graduated from the elite schools. According to a report commissioned by the U.S. venture capital firm Accel, the founders of French unicorns — privately held start-ups valued at more than $1 billion — are the best-educated in Europe, with 81% of founders having a master’s degree, compared to 47% in the UK.

Such a statistic does little to boost France’s mythical reputation for providing liberty and fraternity to its citizens, let alone equality. There is a major fault line in the way it does business, and change is well overdue.

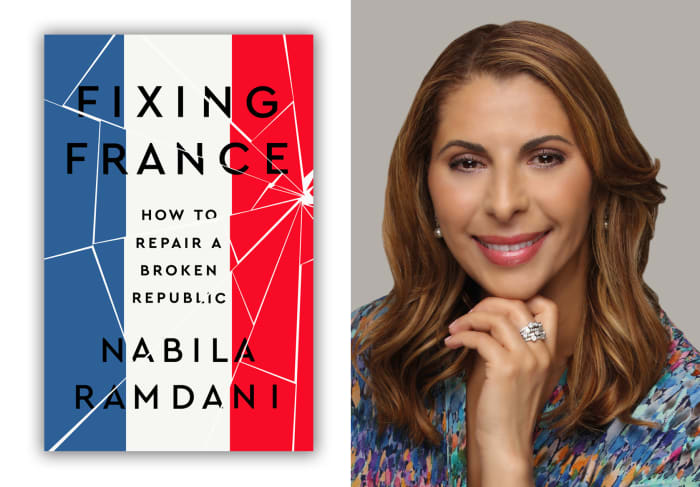

Nabila Ramdani is a French journalist and broadcaster of Algerian descent, and author of Fixing France: How to Repair a Broken Republic (Public Affairs, 2023).

More: Why pricey French bags are better than U.S. tech, according to this analyst

Also read: L’Oreal cut to sell as Deutsche Bank flags China risks