This post was originally published on this site

Medicare on Tuesday announced the first 10 drugs to be selected for a price-negotiation program established under last year’s Inflation Reduction Act, launching a historic and highly contentious process with big implications for pharmaceutical companies, taxpayers and patients.

The drugs selected for the initial round of the negotiation program are Bristol Myers Squibb Co.’s

BMY,

blood thinner Eliquis, Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly & Co.’s

LLY,

heart-failure drug Jardiance, Johnson & Johnson’s

JNJ,

blood thinner Xarelto, Merck & Co.’s

MRK,

diabetes drug Januvia, AstraZeneca’s

AZN,

heart-failure drug Farxiga, Novartis AG’s

NVS,

heart-failure drug Entresto, Amgen Inc.’s

AMGN,

rheumatoid-arthritis drug Enbrel, AbbVie Inc.

ABBV,

and Johnson & Johnson’s blood-cancer drug Imbruvica, Johnson & Johnson’s psoriasis treatment Stelara and Novo Nordisk’s

NVO,

insulin Fiasp.

Those 10 drugs accounted for $50.5 billion, or about 20% of the total, of Medicare Part D prescription-drug costs in the year ending May 31, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare enrollees taking these drugs paid a total of $3.4 billion in out-of-pocket costs for those prescriptions in 2022, the department said.

The manufacturers of the selected drugs have until Oct. 1 to sign agreements to participate in the program. Several pharmaceutical companies with affected products, including Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb and AstraZeneca, have already filed lawsuits challenging the negotiation process. At least eight such lawsuits filed by drugmakers and industry groups are now pending in various U.S. district courts, raising the odds that conflicting rulings will ultimately bring the issue to the U.S. Supreme Court, analysts say.

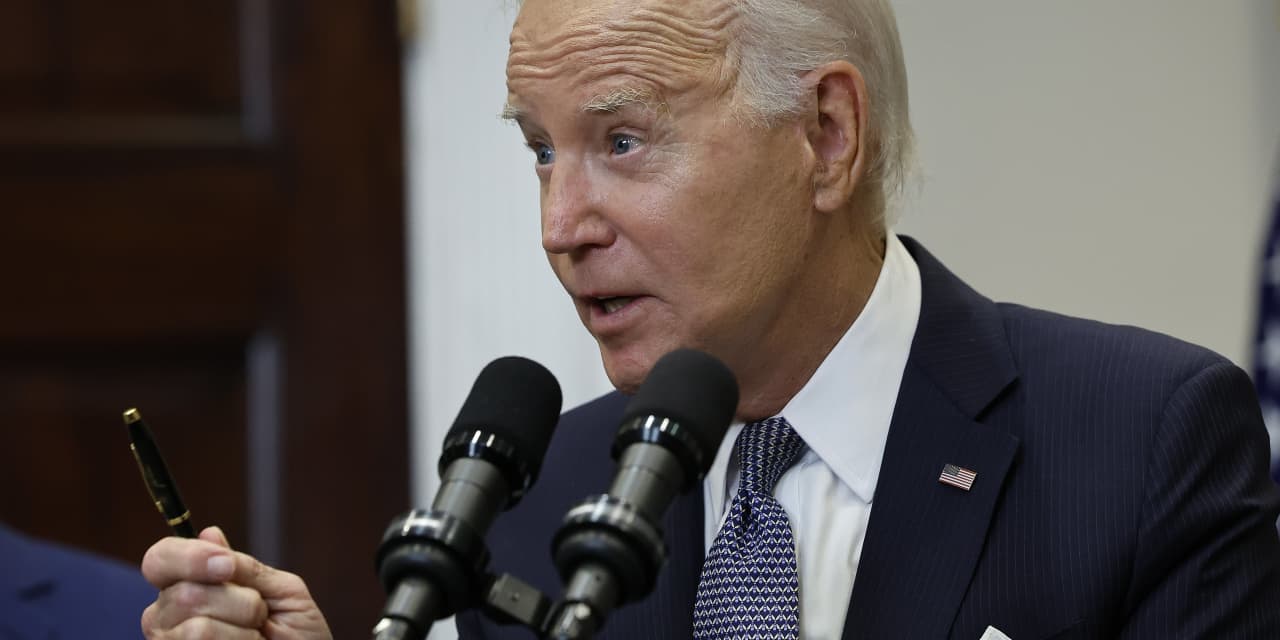

“I am not backing down,” President Joe Biden said in a statement Tuesday in response to industry efforts to block the negotiations. “There is no reason why Americans should be forced to pay more than any developed nation for lifesaving prescriptions just to pad Big Pharma’s profits.”

Asked whether Bristol Myers Squibb would sign on to the negotiation process by the Oct. 1 deadline, a company spokesperson said in a statement to MarketWatch Tuesday, “We have no choice but to sign the ‘agreement.’ If we did not sign, we’d be required to pay impossibly high penalties unless we withdraw all of our medicines from Medicare and Medicaid.”

Other affected industry players also fired back on Tuesday. “The IRA’s price control provisions will constrain medical innovation, limit patient access and choice, and negatively impact overall quality of care,” a Johnson & Johnson spokesperson said in a statement to MarketWatch. The policies “put an artificial deadline on innovation, threatening intellectual property protections and shortening the time frame to deepen our understanding of patients’ unmet medical needs,” the spokesperson said.

More than 80% of Americans favor price negotiations between Medicare and pharmaceutical companies, according to a West Health-Gallup survey released Monday, including 75% of Republicans, 76% of independents and 95% of Democrats. The survey found similar levels of support across age, race, gender, income levels and education.

Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris heralded the negotiation program at a White House event Tuesday afternoon. “Today is the start of a new deal for patients, where Big Pharma doesn’t just get a blank check at your expense and the expense of the American people,” Biden said. The initiative is expected to save the federal government nearly $100 billion over 10 years, according to the Congressional Budget Office. That’s helping to pay for an overhaul of the Medicare prescription-drug benefit that will slash costs at the pharmacy counter for many enrollees, policy experts say, including through a new $2,000 cap on out-of-pocket spending that takes effect in 2025. About 50 million people are enrolled in Medicare prescription-drug coverage.

The effort to rein in prescription-drug costs is potentially lifesaving, some patients and doctors say. “At times I’ve had to forego or ration some of my drugs because they were just so expensive,” Steven Hadfield of Matthews, N.C., said at the White House event Tuesday. “No one in America should have to live this way,” added the 71-year-old, who takes pricey medications for blood cancer and diabetes.

Prescription-drug costs are “a huge issue for my patients,” said Dr. Rob Davidson, an emergency-room physician in western Michigan and the executive director of the Committee to Protect Health Care, an organization of healthcare professionals advocating for quality, affordable care. “Every day I see it,” Davidson told MarketWatch, recalling one patient who couldn’t afford the blood thinner she was prescribed and consequently wound up in intensive care with a massive blood clot in her lung. Working in a rural area with a large Medicare population, he said, he sees that “folks are struggling, making choices between food and medications.”

Drugs qualify for the first round of price negotiations if they’re covered under Medicare’s Part D outpatient prescription-drug benefit, have no bona fide generic or biosimilar competition and have been FDA approved or licensed for at least seven years for small-molecule drugs or 11 years for biologics. The 10 drugs that met all the criteria and had the highest total Part D spending in the 12 months ending in May of this year were selected for the first negotiations.

Medicare will make an initial offer of a maximum fair price for each selected drug early next year, followed by a months-long period when drug companies can make counteroffers before negotiations end in August 2024. Up to 15 additional drugs will be selected for price negotiations for 2027, with more to follow in subsequent years.

Some industry groups have argued that the process doesn’t allow for true negotiation. “Giving a single government agency the power to arbitrarily set the price of medicines with little accountability, oversight or input from patients and their doctors will have significant negative consequences long after this administration is gone,” Stephen J. Ubl, the president and CEO of industry trade group Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, said in a statement Tuesday.

Merck said in a statement that Januvia’s price “reflects its value to patients and society,” adding, “it is critical that any ‘negotiation’ recognizes that value.” The company said it is prepared for the “significant short- and medium-term impact” of the IRA provisions, including impact to Januvia.

For people taking one of the 10 drugs selected for negotiations, the government’s haggling won’t necessarily translate directly into lower out-of-pocket costs, policy experts say. People who pay a copay, or flat dollar amount, for their prescription may continue paying the same amount even if the government negotiates a big price reduction. But for those paying coinsurance — or a percentage of the drug’s price — the negotiations could directly reduce out-of-pocket costs.

The litigation surrounding the negotiations leaves some uncertainty about whether the process will move forward on the timeline outlined by Medicare. In its lawsuit challenging the negotiations, for example, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has asked the court for a ruling on a preliminary injunction request before the negotiation agreements are finalized on Oct. 1.

Rob Smith, managing director at policy-research firm Capital Alpha Partners, wrote in a report Monday that he’s skeptical that the industry’s legal maneuvers will result in an injunction that prevents Medicare from implementing the process on schedule for 2026. But the litigation that long surrounded the Affordable Care Act “highlights how unpredictable these types of legal challenges can be,” Smith wrote.

Shares of drugmakers with affected products traded largely in line with the market Tuesday, as the inclusion of Eliquis, Xarelto, Januvia and several other medicines had been anticipated. The inclusion of some other drugs as negotiation candidates, such as Farxiga and Stelara, had not been as widely expected. The final list was based on Medicare data through May 2023, a senior administration official said on a call with reporters Tuesday, whereas researchers’ forecasts were largely based on older publicly available data.