This post was originally published on this site

Ranjan Dey is stocking up on basmati rice. For every bag of rice he usually buys, he’s storing two extra bags.

Dey is the chef and owner of New Delhi, an Indian restaurant in downtown San Francisco that’s been around for 35 years. He’s one of the business owners in the area who made it through the COVID-19 pandemic despite having to shut his doors in 2020 to prevent the spread of the virus and navigate supply-chain issues after reopening.

Those experiences have left him skittish. When he heard there could be a shortage of certain kinds of rice because of flooding in China and an export ban imposed by India — the world’s biggest rice exporter — he decided to take action.

Ranjan Dey is the chef and owner of New Delhi, an Indian restaurant in downtown San Francisco that’s been around for 35 years. For every bag of rice he buys, he now stores two bags.

Courtesy of Ranjan Dey

“I have no idea what could happen,” Dey said. “I’m just being cautious because I can’t raise my menu prices overnight.”

The export ban on certain kinds of rice that was announced by the Indian government in July could lead to a global rice shortage, some analysts have warned. More than 90% of the world’s rice is produced and consumed in the Asia-Pacific region, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization.

But will any shortages have an impact on U.S. consumers? Is Dey just being pragmatic, or is he overreacting?

Rising food prices suggest he may have cause for concern: rice prices rose 6.5% on the year in July, government data released earlier this month showed. To put that figure in context, food prices overall rose by 4.9% on the year in the U.S.

He does not appear to be the only person stocking up: 38% of consumers who buy rice say they have noticed a dearth of the staple on store shelves, according to a survey released this month by Numerator, a consumer research firm.

“As retailers saw with toilet paper during the pandemic, shortages can be self-perpetuating as customers stock up on products because they fear there will be a shortage.”

Among consumers who buy rice regularly, 53% said they are loyal to a specific brand, and 75% said they tend to buy specific varieties — such as jasmine, basmati or long-grain white rice. Meanwhile, 44% said they would switch to a different variety, 35% would buy a different product like pasta and 34% would shop at different retailers to try to find their preferred brand or variety.

As retailers saw with toilet paper during the pandemic, shortages can be self-perpetuating as customers stock up on products because they fear there will be a shortage. The announcement of the Indian export ban led to some panic buying in Texas, for example.

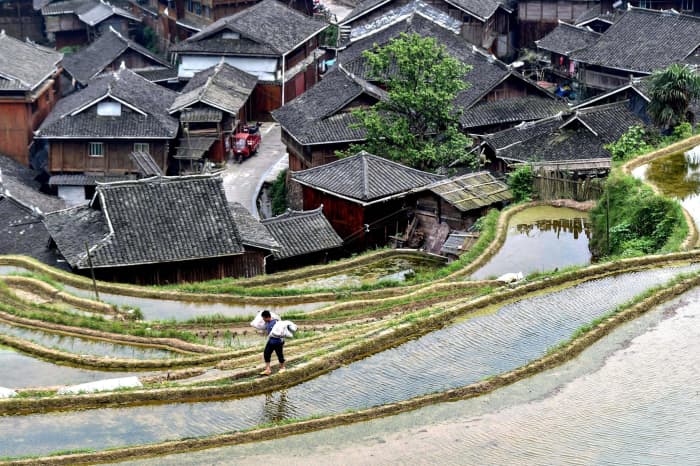

A farmer walking along terraced rice paddy fields in China’s southwestern Guizhou province. Last summer, floods hit the southern part of China, the world’s largest producer of rice. This summer, floods plagued China’s northeastern provinces.

str/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

Frequent droughts and floods disrupt the global rice supply

Charles Hart, a commodities analyst at Fitch Solutions, is predicting a global rice shortage this year because of extreme weather conditions. He cites decade-high prices, with rough rice futures trading at $18.80 per hundredweight unit — which is equal to 100 pounds — up from $12.15 in August 2019.

Rice is usually grown in flooded fields, which makes the crop particularly vulnerable to drought as well as flooding. Last summer, heavy monsoon rains and floods hit the southern part of China, the world’s largest producer of rice. This summer, floods have plagued China’s northeastern provinces, which produce almost a quarter of the country’s rice supply.

“Heavy flooding in recent years in Pakistan, the world’s fourth-largest rice exporter, damaged almost 80% of the rice crop in a region where almost half of the country’s rice is grown.”

Heavy flooding in recent years in Pakistan, the world’s fourth-largest rice exporter, damaged almost 80% of the rice crop in a region where almost half of the country’s rice is grown, according to estimates from International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development and the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council.

The most recent disruption comes from India, which is responsible for over 40% of the global supply. Erratic weather — too much rain in the north and not enough in the south — and an increase in food prices in the country led the government to ban the export of non-basmati white rice in late July. The ban is aimed at stabilizing the domestic rice supply ahead of a general election in spring 2024.

Basmati rice — a region-specific designation for rice that’s similar to that of Champagne for wine — is only grown in one particular Himalayan region in India and Pakistan.

More weather disruptions could be coming. El Niño, a climate pattern caused by warmer water in the Pacific Ocean that can have significant effects on global weather, arrived in early June and will continue until early next year, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. That means there will be a higher risk of heavy rainfall and severe drought in many locations around the world.

Russia’s war in Ukraine also continues to adversely affect the global supply of grains, according to a recent research note from JPMorgan. Ongoing safety risks to the Black Sea Grain Initiative, a plan to transport grain securely out of Ukraine, continue to push up grain prices. Ukraine and Russia together produce around 30% of the World Food Program’s exported wheat supplies, 20% of exported corn and 75% of exported sunflower oil.

Read: El Niño has potential to disrupt the outlook for sugar, rice and other consumer staples

An Indian farmer sprays fertilizer in the paddy fields at Medak district, 60 kilometers from Hyderabad. Last month, India — the world’s biggest rice exporter — announced an export ban on certain types of rice.

noah seelam/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

Global supply issues may continue to push up rice prices

For now, U.S. consumers should be shielded from the impact of geopolitical issues that are affecting the global rice supply, analysts said. About 80% of the rice consumed by U.S. families is produced domestically, primarily in six states — Arkansas, California, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri and Texas — according to the U.S. Rice Federation, an industry group.

This year is expected to be a good year for U.S. rice production, because farmers are planting more, analysts said.

Domestic rice production is expected to reach 203.6 million hundredweight, 27% more than last year, according to the Department of Agriculture. As a result, U.S. farmers might even export more rice in 2023 than they did last year, analysts said.

“About 80% of the rice consumed by U.S. families is produced domestically, primarily in six states — Arkansas, California, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri and Texas.”

Even so, global supply issues may continue to push up rice prices as countries act to secure their own supplies. U.S. rice imports have nearly tripled over the past two decades, according to the USDA. “Most rice imports are specific aromatic varieties from Asia — jasmine from Thailand and basmati from India and Pakistan,” it said.

In recent years, around 80% to 85% of Thailand’s rice shipments to the U.S. have consisted of Thai Jasmine, a premium long-grain fragrant rice. But in Thailand, which has seen a prolonged period of low rainfall, officials have urged farmers to plant less rice to conserve water. Higher global rice prices will also affect the price U.S. consumers will be paying for Thai rice.

“If you are a loyal consumer of Thai rice, this is not a good time to be a Thai rice consumer,” said Tanner Ehmke, lead economist on grains and oilseeds at CoBank, an agricultural lender and financial-services company.

U.S. consumers could further feel the effects if other major rice exporters — China, Thailand, Vietnam and Pakistan — follow India’s lead and put export restrictions on rice. In spring 2008, for example, rice prices spiked in the U.S. due to international trade restrictions, panic buying by several large importers, a weak dollar and record-high oil prices.

“The hope is that everyone is going to have cooler heads and that they won’t do that,” Ehmke said.

In San Francisco, Dey, the Indian restaurant owner, said he thinks most disruptions will be resolved in two months, and having two extra bags of basmati rice on hand for each bag he normally buys will tide him over for that long if needed.

“So for two months, I’m good — I can have that steady price,” he said.

Also read: India Bans Some Rice Exports. What That Means for Global Prices.