This post was originally published on this site

U.S. President Joe Biden’s economic policies depart sharply from those of former President Donald Trump, but both share a commitment to limiting the risks of trade with China and an ambivalence toward market-driven globalization.

Notably, Biden has kept Trump’s tariffs on Chinese imports. Biden’s policies favor cooperative arrangements to harmonize labor, environmental and industry standards, empower women and minorities and combat climate change.

U.S. limits on high-tech exports to China and industrial policies for autos and green energy have been characterized as attacks on the global trading system and “decoupling” was briefly the buzzword for policy toward China.

That’s too simplistic. From the end of World II to 2009, trade’s share of global GDP rose from 20% to 61% ,and has since fluctuated around 57%. U.S. trade and investment with China continue to increase, but at a slower pace.

The Biden administration has insisted it seeks to derisk trade and not disengage from mutually beneficial commerce. The U.S. will pursue economic ties that reflect greater sensitivity to the vulnerabilities posed by specialized supply chains and military competition.

The disruptions caused by COVID, climate change, the internet and artificial intelligence are inspiring the Biden administration to seek cooperative arrangements that enhance flexibility with friends in the Indo-Pacific Framework, U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council and bilateral agreements such as with Taiwan.

Absent offering increased market access through tariff reductions, the administration’s objectives can look protectionist. Promoting trade by whatever means usually entails enhancing specialization based on comparative advantages and imposes labor market adjustments. Trade agreements that protect workers and union jobs run contrary to that kind of thinking and risk pushing Asian trading partners into the arms of China.

Derisking has three components:

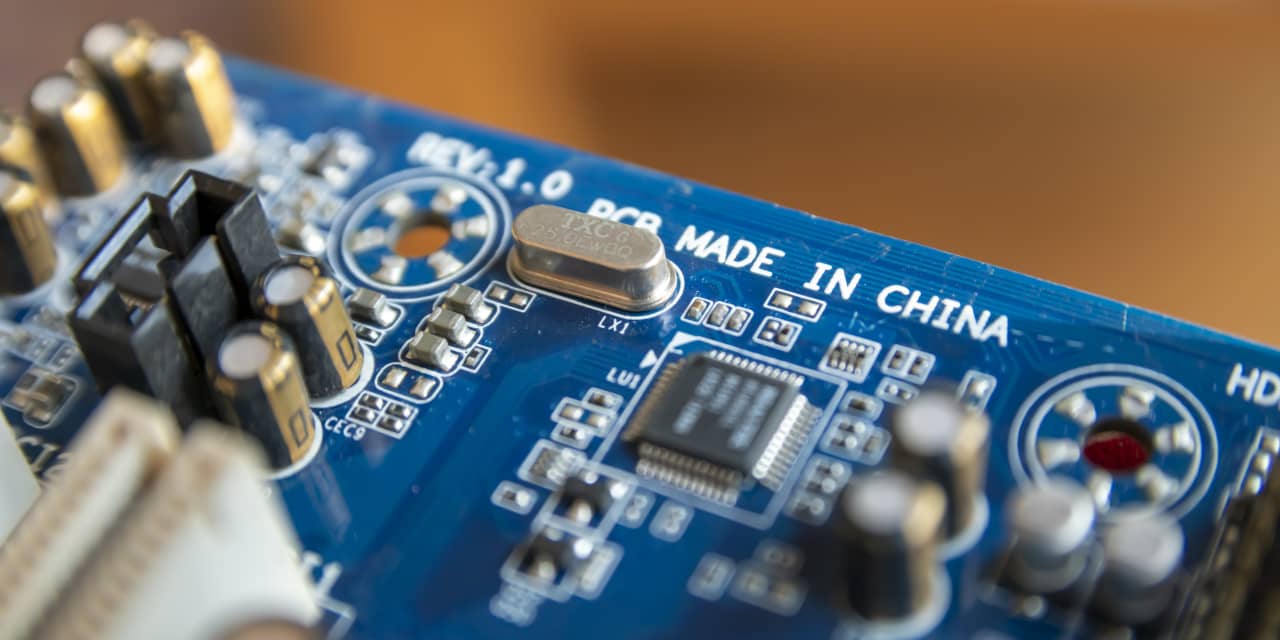

1. Limiting the transfer of cutting-edge technology to China — for example through U.S., Japanese and Dutch exports of chipmaking equipment — that could diminish American advantages in cutting-edge military weapons.

2. Reducing China’s strategic leverage where it has become a dominant supplier — for example, rare earth minerals, lithium processing and solar panels.

3. Diversifying imports to limit risks of trade disruptions that may result from wars, pandemics and natural disasters.

China’s response to COVID damaged its reputation as a reliable global supplier. After taking losses by abandoning investments after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, multinationals are moving to China-plus-one strategies. For example, Apple

AAPL,

is developing a new value chain in India and seeking to reshore some components as a simple matter of corporate risk-management.

In all this, the culpability and reach of U.S. government policy are limited.

A new national security law in China puts Western businesses at risk of criminal prosecution for collecting ordinary business information necessary for sound corporate decision-making. Chinese authorities recently interrogated the staff of the U.S. consultancy Bain & Company and raided the Beijing offices of the New York-based due diligence firm Mintz Group, arresting five of its staff.

Recently, the extremes of President’s Xi Jinping’s paranoia were on full display in the entertainment industry. Chinese authorities fined a talk show $2 million dollars for a comedian’s joke about a Xi military slogan, arrested a woman for defending him and then shut down a range of unrelated live acts and concerts across the country.

Xi’s fears are without bounds and hauntingly similar to the anti-Western hysteria that Russian President Vladimir Putin has cultivated. That alone should give Western businesses pause about further engagement with China.

China is too big to ignore

Led by J.P. Morgan Chase

JPM,

the largest U.S. financial institutions are reducing exposure in China, but many multinationals can’t ignore it; China commands 18.5% of global GDP as measured by purchasing power parity.

Germany, the locomotive of the EU economy, is more challenged than the United States by the transition from fossil fuels, artificial intelligence and other digital technologies. And it is terribly dependent on exports to China. Germany’s BASF

BASFY,

Daimler, Volkswagen

VOW,

and BMW

BMW,

account for 34% of all European direct investment in China and are strongly resisting German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s pleas to shift away from China.

Investment is often a substitute for trade — limiting exports is of little value if Western firms build facilities in China to service its markets. As the Biden administration seeks to develop an investment screening program for U.S. businesses, the EU is plainly not inclined to go as far in curbing capital flows into China.

Virtual autarky may be the only way to deny the Chinese and Russians of what they need. For example, ordinary chips used to make household appliances can be used by the Russians to make weapons. Even with the best export controls, cutting China off from what it requires to make the best weapons or insulating the West from geopolitical risks of commerce is going to be a very tough climb.

Peter Morici is an economist and emeritus business professor at the University of Maryland, and a national columnist.

More: CEOs say their companies can’t afford a cold war between the U.S. and China

Also read: China is feeling the pinch from a weakening global economy and U.S. restrictions