This post was originally published on this site

A new study goes a long way toward solving what many call the “Social Security claiming puzzle.”

The puzzle is why so many retirees claim their Social Security benefits at earlier ages, even though the nearly universal advice from financial planners is to delay claiming as long as possible. Among retirees who don’t claim at their Full Retirement age (FRA)— age 66 for those born before 1960, age 67 for those born thereafter—58% are early claimers.

Read: Should Social Security be invested in the stock market?

Early claiming is rational in certain cases, such as when the claimant is in poor health or comes from a family with a history of shorter life expectancies. But the incidence of early claiming is far greater than can be explained by these other variables, and it has huge financial consequences. Researchers recently calculated that, relative to what is optimal given those variables, early claiming reduces the present value of lifetime discretionary spending by $182,370 for the median worker approaching retirement.

Why, then, do retirees leave so much money on the table? A big part of the answer, according to this new study, has to do with two psychological traits: Our sense of “psychological ownership” of the Social Security benefits we’re slated to receive, and how much we fear losses. It’s titled “Social Security Claiming Intentions: Psychological Ownership, Loss Aversion, and Information Displays,” the study was conducted by Suzanne Shu, a professor at Cornell University, and John Payne, a professor at Duke University.

By “psychological ownership,” the professors are referring to the feeling that something is “mine.” Surveys that they conducted tested for this feeling by asking respondents to react to statements such as “I feel that I have earned these retirement benefits,” and “the Social Security benefits that I will receive come from the money that I contributed.” The professors found that those who were more likely to agree or strongly agree with these statements were more likely to say they were going to be an early claimer.

Read: How big will Social Security’s 2024 COLA be?

No one knows for sure why a sense of ownership is associated with being an early claimer. But researchers speculate that when people are considering money that they consider theirs, they more acutely feel a sense of loss if they don’t get it all back. So even though they would more likely have a higher total retirement standard of living by being a later claimer, they run the risk—if they die before their average life expectancy—of not getting all “their” money back. So they tend to claim early.

This psychological trait is related to the other that the professors found correlated with early claiming: Loss aversion. This refers to our tendency to fear losses more than we desire gains. Would you, for example, take a bet on a coin flip if you get $150 if you win and $100 if you lose? If not, how much more than $150 would you require when winning in order to take the bet? By asking a series of such questions, the professors were able to determine respondents’ aversion to loss. Those with higher levels of such aversion were more likely to be early claimers.

Trying to convince near-retirees to be more rational

The obvious implication of these findings would be to design educational materials that directly address the financial cost of these psychological traits, and have financial planners discuss those costs with their clients. But another of the professors’ findings suggests this is easier said than done.

Take a simple data presentation that has been found to increase retirees’ and near-retirees’ willingness to invest in annuities. Since being a later Social Security claimer is the functional equivalent of purchasing an inflation-indexed annuity, you’d think that a similar presentation would have a similar impact on the claiming decision. But it didn’t.

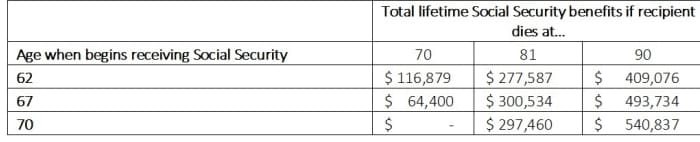

The data presentation shows the increased benefits that would be received by beating average life expectancy. To illustrate, consider a 62-year single male who is slated, at his full retirement age of 67, to receive the average Social Security monthly benefit of $1,789. The following matrix is similar to what the professors used in their surveys.

As you can see, the early claimer is ahead of the late claimer if death occurs at age 70. Age 81—the life expectancy of a 62-year old male—represents close to a break-even point. And if the recipient lives to age 90, late claiming comes out over $130,000 ahead—as you can see from the bottom right quadrant of this matrix. (This illustration doesn’t take Social Security’s automatic cost of living adjustments into account, which would change the numbers in this table but not the overall lesson.)

The professors were expecting that this sizable increase in total benefits would be enough to convince the potential Social Security recipient to delay claiming. But it had the opposite effect. The reason, they speculate, is that potential recipients focus instead on what happens if they die before their average life expectancy. If they are a late claimer and die at age 70, as you can see, they leave more than $116,000 on the table.

The professors speculate that what’s at play here is the loss aversion they also documented. Being a late claimer is an implicit bet that is similar to the coin toss in which you get $150 if you win and must pay $100 if you lose.

In an interview, Payne said that he and his co-author don’t take a position on whether potential Social Security recipients should or shouldn’t be averse to losses, or should or shouldn’t have a sense of psychological ownership of their future Social Security benefits. Their point instead is to show just how much these personality characteristics are impacting the Social Security claiming decision.

If policy makers and financial planners want to change potential recipients’ behavior, they will need to address those characteristics head on.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.