This post was originally published on this site

The U.S. debt-ceiling drama on Capitol Hill makes for great theater, but is little more than a sideshow for bond investors. That’s because the shorter-term direction of U.S. interest rates is almost entirely a function of the Federal Reserve’s actions, and not the debt-ceiling negotiations in Washington.

Yet judging by the saturated coverage of these negotiations in the financial media, many bond investors have come to believe that interest rates are heavily dependent on the debt ceiling.

History does not support their concern. Although the U.S. government has never defaulted on its debt, it came close in 2011. For the first half of that year there were several warnings from the rating agencies that they were considering the previously unthinkable — a downgrade of the U.S. government’s credit rating. These warnings came to pass in July and August 2011, when two rating agencies did in fact lower their ratings. The “full faith and credit” of the U.S. government was no longer something that could be taken for granted.

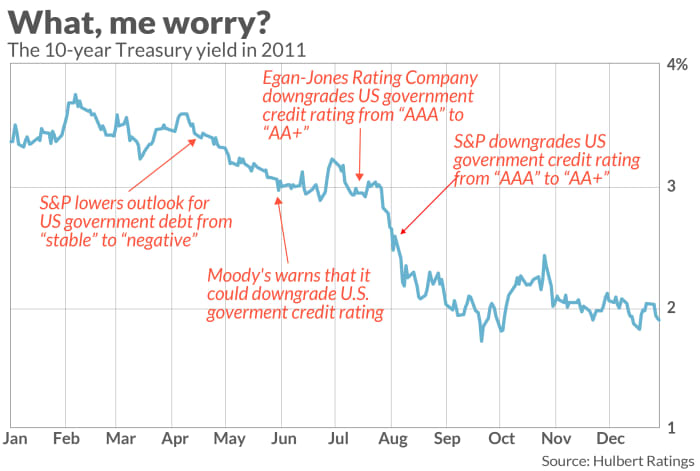

Nevertheless, interest rates, which had been declining before the warnings and eventual downgrades, continued to fall thereafter, as you can see in the chart below.

Indeed, someone looking at the chart without being aware of this history would not suspect that an intense debt-ceiling negotiation was raging in Washington in 2011.

The 10-year Treasury

TMUBMUSD10Y,

yield back then stood at 3.4% when Standard & Poor’s in mid-April issued its negative outlook on U.S. debt, for example, and 3.0% in early June when Moody’s did the same. In July, the Egan-Jones Rating Company downgraded the U.S. government’s credit rating from “AAA” to “AA+,” and in early August S&P followed suit.

After that second downgrade, the 10-year Treasury yield stood at 2.6%. If rates had been declining because of concern about the debt ceiling and a possible default, then rates should have turned back up after Congress kicked the can down the road and the immediate threat of default was averted. Yet the 10-year yield was even lower by the end of 2011, at 1.9%.

This history doesn’t mean that a government default would have no economic impact on bonds. But that impact will be indirect and longer-term, via putting a damper on economic activity and increasing the government’s borrowing costs. Counterbalanced against that will be upward pressure on short-term interest rates because of the uncertainty surrounding a possible default. The net effect may therefore be modest. The Fed’s fight against inflation will have a more immediate and direct effect on rates.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: A U.S. default would destabilize the financial ecosystem that investors swim in, strategist warns