This post was originally published on this site

If you’re shopping for a house or car this spring, you’ll probably pay a much steeper interest rate than if you had bought the same thing in March 2022. Likewise, if you’re carrying a credit-card balance, the annual percentage rate that now applies is almost certainly higher than it was in early 2022.

It’s been a year since the Federal Reserve started ratcheting up its benchmark interest rate from nearly zero in a bid to tame inflation. Wednesday’s 25-basis-point increase was the central bank’s ninth straight hike of its federal-funds rate.

And while the inflation rate ebbs from four-decade highs, interest on debt is starting to pile up. “It’s kind of insidious,” said Kelly LaVigne, Allianz Life’s vice president of consumer insights. “It makes everything so much more expensive without you realizing it.”

For people who are acutely aware of their debts, higher rates intensify the woes, said Ashley Agnew of Centerpoint Advisors in Needham, Mass. “It feels more like a punishment than an interest rate,” she said.

The Fed’s rate decisions have huge implications for the economy and the stock market — especially with questions now being raised about the health of the banking sector. And while the banking system is “sound and resilient,” the Fed said in its statement on Wednesday that “recent developments are likely to result in tighter credit conditions for households and businesses.”

On Wednesday afternoon, the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

S&P 500

SPX,

and Nasdaq Composite

COMP,

were all trading lower after Powell spoke with reporters.

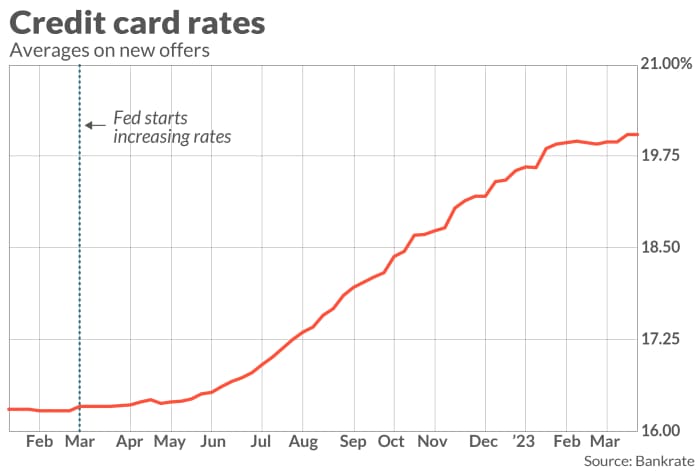

Credit cards are a key example of the sneaky lagging effects of interest rates when costs are high, said Ted Rossman, a senior industry analyst at Bankrate.com. “It made a bad situation worse,” he said. “The cumulative effect is really significant.”

The central bank’s fed-funds rate directly affects the prime rate that credit-card issuers use to determine annual percentage rates, or APRs. It can take one or two billing cycles for a Fed rate hike to affect the APR on an existing account, but it can increase the rate for new offers within days, experts said.

Americans had a total of $968 billion in credit-card debt at the end of 2022, according to the New York Fed. Credit-card accounts carrying a balance averaged an APR of 20.4%, up from 16.4% in the fourth quarter of 2021, according to Fed data.

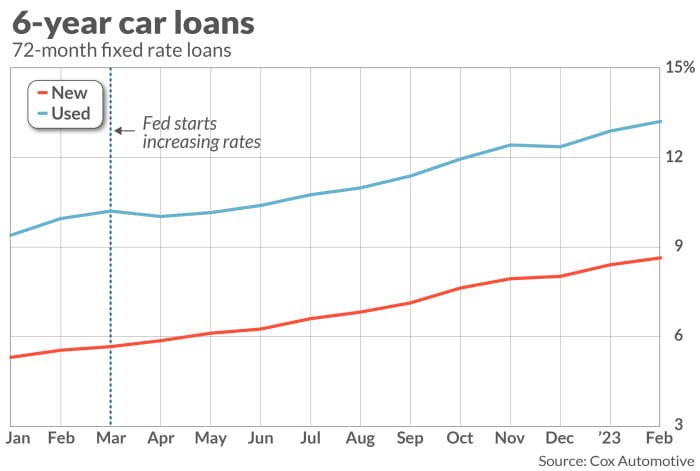

The Fed’s rate also indirectly influences the rates that lenders use for car loans and mortgages and the rates banks use to determine annual percentage yields on savings accounts.

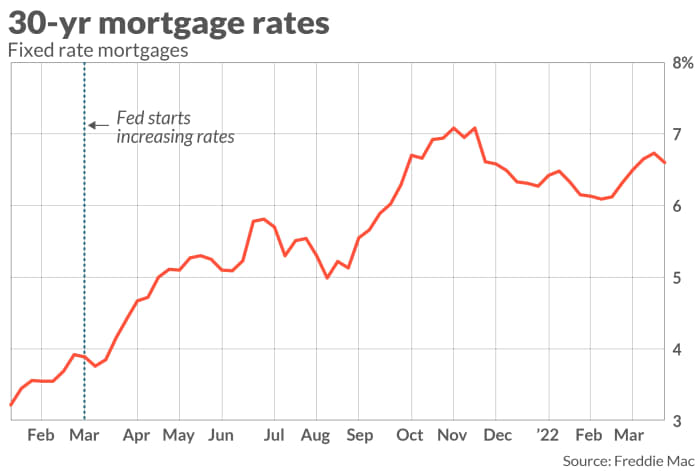

Would-be home buyers can easily see the effects of a change in mortgage rates on their monthly payments. Mortgage demand increased last week after rates declined for a second week.

“Home buyers in 2023 have shown themselves to be quite sensitive to any changes in mortgage rates,” said Mike Fratantoni, senior vice president and chief economist at the Mortgage Bankers Association. “With this move from the Federal Reserve, MBA is holding to its forecast that mortgage rates are likely to trend down over the course of this year, which should provide support for the purchase market.”

Higher rates can also make buying a car even more unaffordable at a time when the average monthly payment on a new car is above $700.

But after years of relatively low rates, the increases are putting a new gloss on savings accounts.

For example, a high-yield online savings account now averages 3.5%, up from 0.49% in March 2022, according to data from DepositAccounts.com. At the same time, inflation is sapping consumers’ ability to save cash, said Ken Tumin, the site’s founder and editor.

“The hope is once inflation goes down, we’ll have a period — at least some period — where we’ll have some real positive yields on savings and CDs, where the savings-account rate is above the inflation rate,” Tumin said.

Agnew has a client at Centerpoint Advisors who is in her 20s, at the start of her career and financial life. It took the quick rise in interest rates for her to realize that money could grow in a savings account and that it wasn’t a marketing gimmick. “Oh, I thought banks just did that to be nice,” Agnew recalled her client saying.

And as interest rates have increased, so has the principal borrowers owe. Americans had $16.9 trillion in mortgage and consumer debt at the end of 2022, according to the New York Fed.

It’s tough to say what portion of those debts is interest. But there are other peeks into the ways higher interest rates are affecting consumers.

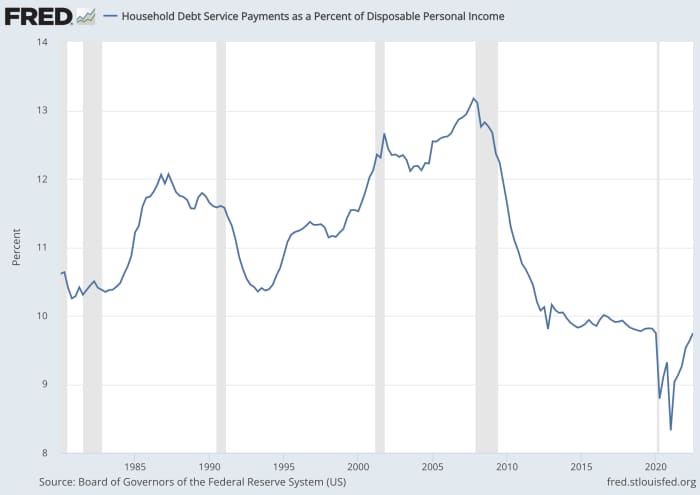

The interest paid on consumer debts, including credit cards, now eats up the same amount of disposable income it did at the start of the pandemic. Consumer debt-service payments account for 5.75% of disposable personal income, according to the Federal Reserve’s most recent report, from the third quarter of 2022.

Add in mortgage interest, and 9.7% of a household’s disposable income was going toward the borrowing costs for housing and consumer debt during the third quarter of last year. That’s back to the level in the first quarter of 2020, although it’s still low when you look at the big picture.

The real question is what’s next, said Allianz Life’s LaVigne. The data doesn’t capture how much interest people were paying at the end of last year and how much they are paying now.

“It doesn’t look horrible, but it could be a shot across the bow [signaling] that we ought to curb spending a little bit more,” he said.

Aarthi Swaminathan contributed to this report.