This post was originally published on this site

Small has been beautiful this year on Wall Street. That’s because the smallest-cap stocks within the S&P 500

SPX,

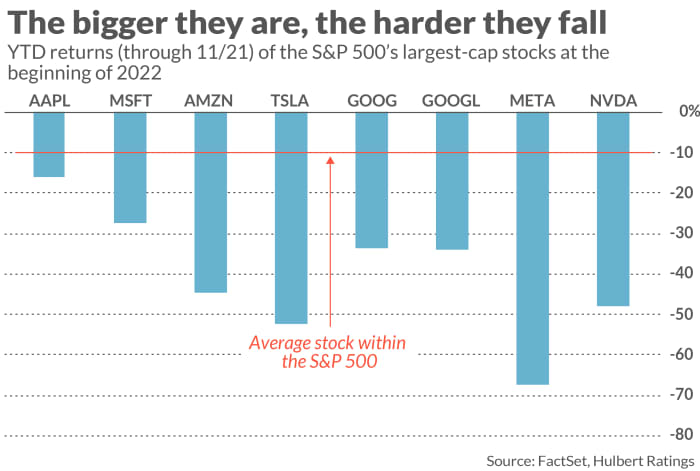

have far outperformed the largest-cap stocks since January. The eight stocks with the largest market caps at the beginning of the year—which at the time represented a top-heavy 27.2% of the total market cap of the entire index — have lost an average of 40.4% so far this year (through Nov. 21), according to FactSet. That’s more than three times the 9.5% average loss among the remaining 490+ stocks in the S&P 500.

Meta Platforms

META,

is the biggest year-to-date loser, down 67.3%, but it certainly isn’t the only stock bringing down the average. NVIDIA

NVDA,

the 8th largest stock in the S&P 500 at the beginning of 2022, was down 47.9% through the end of October, and Amazon

AMZN,

the third largest, was down 44.5%. The chart below shows how the eight largest-cap stocks in the S&P 500 at the beginning of the year have lost more than the average.

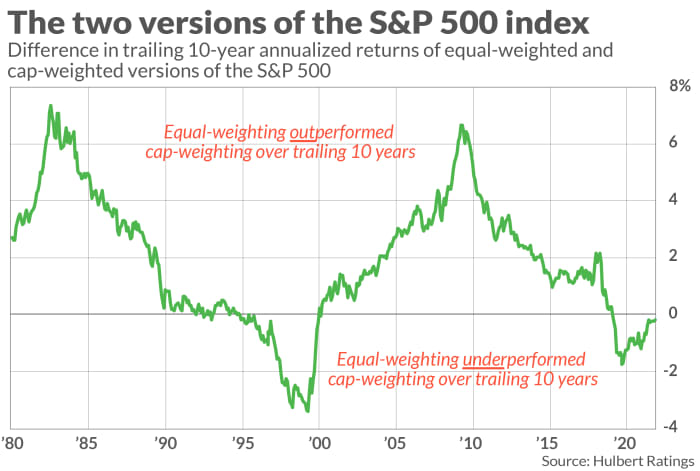

This stark contrast explains why the equal-weight version of the S&P 500 index has outperformed the traditional, cap-weighted, version — the version you see reported every day in the financial press. The equal-weight strategy gives each of the index’s component stocks the same weight in the index, while the cap-weighted approach ranks each stock according to its market value. Given that stocks representing more than a quarter of the S&P 500 index have lost more than three times the average among all the other components, it is little surprise that the cap-weighted S&P 500’s year-to-date return is far behind the equal-weight version — by 6.0 percentage points.

That’s the biggest alpha for the equal-weight version in more than a decade, assuming this 6.0 percentage point differential holds up through the end of the year. You have to go back to 2010 to find another calendar year in which the equal-weight alpha was bigger. At that time the alpha was 6.3 percentage points.

The equal-weight version of the index does not always outperform the cap-weighted version, of course. Long-term data paint a picture of the two versions in a virtual tie. Since 1971, which is how far back S&P Global has calculated the equal-weight version’s performance, the equal-weight version has produced a dividend-adjusted return of 12.2% annualized, in contrast to 10.8% for the cap-weighted version. But the equal-weight version’s higher return was produced with 13% more volatility, which is one measure of risk. On a risk-adjusted basis, the two are almost neck-and-neck, with equal-weight slightly ahead.

This slight advantage largely disappears once transaction costs and management expenses are taken into account. Transaction costs are higher for the equal-weight version because, by design, it must undergo more periodic rebalancing transactions than the cap-weighted version. The annual turnover ratio for the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust

SPY,

is 2%, for example, in contrast to 38% for the Invesco S&P 500 Equal Weight ETF

RSP,

Management expenses are also higher for the Invesco ETF (0.20% per year of assets under management) than for the SPDR product (0.0945% of AUM).

The Invesco ETF has existed only since 2003, so we have just two decades of real-world experience for the two weighting schemes. Since then the equal-weight ETF has slightly beaten the SPDR ETF on a raw, unadjusted basis but lagged on a risk-adjusted basis.

What to expect

Lawrence Tint, the former U.S. CEO of Barclays Global Investors, the organization that created iShares (now part of Blackrock), believes it’s a tossup which weighting scheme will do better in coming decades. In an interview, Tint said there will be times when the largest-cap stocks will suffer disproportionately, like this year, and when that happens the cap-weighted version will lag the equal weight version. But, Tint added, there will be other times when it’s just the opposite.

Tint said he’s unaware of any theoretical reason why the relative advantage should always go one way or the other.

Tint’s argument receives historical support from the chart above, which plots the difference in trailing 10-year annualized returns of the equal-weight and cap-weight version of the S&P 500. This difference has oscillated between periods of equal-weight outperformance and underperformance. Note carefully that these returns are calculated based on the theoretical returns of the indexes themselves and don’t take transaction costs and management expenses into account. On an after-cost and after-fee basis the data series in the chart would shift downwards.

One approach you might take to deciding between the cap- and equal-weighted versions of the S&P 500 is your tolerance for volatility-related risk. Since the equal-weighted version historically has been 13% more volatile than the cap-weighted, you could view it as the functional equivalent of purchasing the cap-weighted version on 13% margin.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

Also read: What Black Friday and Cyber Monday sales tell you about retail stocks, recession and the economy