This post was originally published on this site

Polarization is the top issue facing the world today — and it’s on the rise. For example, a recent poll from the Pew Research Center showed that majorities in both the Republican and Democratic parties view members of the other party as more closed-minded, dishonest, immoral and unintelligent than other Americans.

We encounter polarization at every turn. Social media used to be a place to reconnect with long lost friends. Now it’s become a platform to spout political views and unfollow anyone who disagrees. Diversity programs were supposed to increase inclusion and belonging. Instead, they seem to exhaust everyone, including the individuals leading them. Families and friendships are being destroyed because we can’t agree on issues of race, religion and politics.

Rather than sequestering in our echo chambers and “canceling” anyone who disagrees, we can turn to cultural intelligence, a scientific model that has helped organizations and executives build more inclusive, equitable cultures. This same model can help us talk with co-workers, friends and family members who see the world differently than we do.

Here are four questions to help address polarizing topics with cultural intelligence:

1. Would you be open to considering a different perspective?

The No. 1 trait that predicts cultural intelligence is openness and curiosity. If you aren’t open to considering a different way of thinking or behaving, it’s impossible to be culturally intelligent.

For example, when someone is arguing about Donald Trump, “woke” ideas, or the forgiveness of student debt, I stop and ask, “Would you be open to considering a different perspective?” Rarely does someone respond, “Hell, no!”. But if they do, there’s little use in talking any further. I simply state my opinion and move on.

But beware. I’ve sometimes been too quick to assume someone is closed. My preferred conversation style is an amicable, diplomatic approach, even when discussing issues I feel strongly about. I can wrongfully interpret a more assertive confrontational approach as someone who is closed-minded when in fact, it might just be a difference in style. Other times I’ve been talking with someone who uses measured, conciliatory language only to find out they weren’t open at all and were simply baiting me.

Use these indicators to assess openness:

- Do they ask open-ended questions, demonstrating a genuine desire to understand?

- Are they’re willing to admit a statement was wrong or exaggerated?

- Can they point to something they respect about the “other” side, and something that troubles them about “their” side?

- Are they willing to say, “I don’t know”?

2. Have I accurately understood your perspective?

Perspective-taking is one of the critical skills we assess and teach as part of cultural intelligence. Social psychologist Adam Galinsky led a study on perspective-taking where students were shown a photo of an elderly man sitting on a chair next to a newspaper stand. The students were asked to write a short essay about a typical day for the man in the photo. Galinsky divided the students into three groups, telling the first group to simply look at the picture and describe the man’s day. The second group was told to write a description without using any stereotypes about elderly men. The third group was instructed to write the essay in the first person as if they were the man in the picture.

The students in the first group used negative stereotypes to describe the man (lonely, declining physically, forgetful). The students told to avoid stereotypes wrote more neutral descriptions, making up scenarios about how the man might spend his time and what he thinks about. But the students who were asked to write the essay in the first person wrote the most positive descriptions of the man’s life, referring to his sage wisdom, his wide range of friendships and the joy he finds in the simple things of life.

Perspective-taking increases the likelihood that individuals will not only be less discriminatory in their thoughts and behaviors but will develop more positive viewpoints. When interacting with a friend or colleague about a polarizing issue, see if you can both describe the other’s perspective in neutral terms, ideally in the first person.

Read: If you must talk politics at Thanksgiving dinner, follow these rules of engagement

3. How would you solve this problem?

A study on political extremism found that many citizens had little understanding of the policies they opposed or supported. They just knew that something didn’t sit right with them. But individuals were more willing to open their minds to alternative approaches when they were asked how their preferred policies would work. Having to talk through the complexities of health-care legislation or immigration policy caused people to see the nuance of the situation and acknowledge gaps in their knowledge. Overcoming polarization on issues like climate change or how to effectively promote racial equity requires an emphasis on problem-solving.

Pay attention to how your counterpart wants to see change happen. Push them to explain the “how” rather than just repeating the “what.” How would you address inequitable pay, disproportionate rates of arrest, health disparities, etc.?

4. Where are you willing to compromise?

Overcoming polarization will never happen unless there’s a willingness to adjust our thinking and behavior. The culturally intelligent look for ways to adapt their behavior without compromising what’s core to their values and identity.

For example, Sylvia is a French executive working for a Middle Eastern company in Dubai. She’s the only woman on the executive team, and the majority of leaders across the company are men. When interviewed for the position, Sylvia made it clear that she expected to be treated respectfully and equitably. They assured Sylvia they would respect her and demonstrated it with pay, job title and a direct reporting line to the CEO. Sylvia was unwilling to put on a submissive, deferential act to fit in with the male-dominated culture, but she found ways she could adapt to the cultural norms without losing herself in the process.

In France it wasn’t uncommon for Sylvia to have lunch with a male colleague or client as a part of developing rapport and trust. But she avoids those kinds of lunches in her new role, believing it’s one small way to respect the boundaries between work and personal interactions across genders. When Sylvia joins the executive team for a work-related dinner, she refrains from ordering alcohol. But when she discovered that the company was ignoring a number of safety regulations, putting their construction teams at risk, she raised the issue immediately. She communicated her concern respectfully but unapologetically and forcefully.

Berrett-Koehler Publishers

This is what action looks like. Sylvia is comfortable in her own skin and she’s not trying to be all things to all people. But she adapts as needed to accomplish a larger objective. In the same way, when we confront polarizing topics, we can almost always find some areas where we can adjust our thinking and behavior without compromising our core values and identity.

There are no easy answers for how to address polarization. But together, we can build a more culturally intelligent world, one conversation at a time.

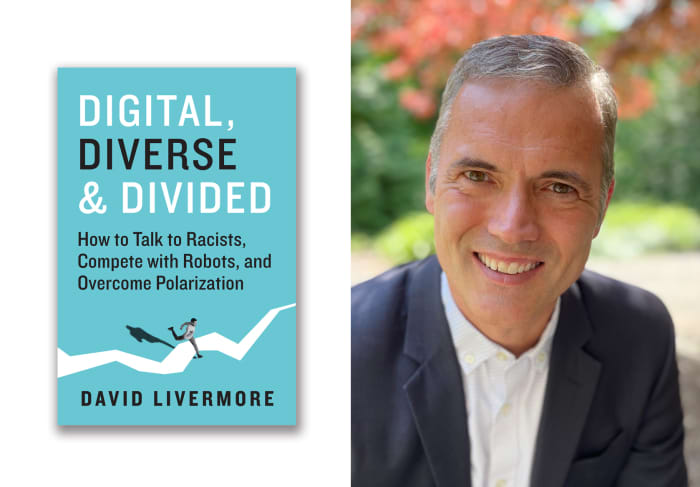

David Livermore is a social scientist and thought leader devoted to the topics of cultural intelligence and global leadership. He’s a founder of the Cultural Intelligence Center and the author of “Digital, Diverse & Divided: How to Talk to Racists, Compete with Robots, and Overcome Polarization” (Berrett-Koehler Publishers,2022).

More: Polarization doesn’t capture what’s happening to Americans right now

Also read: Do your relatives pick fights on climate change? Push back with investment tips.