This post was originally published on this site

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org.

Within two years of my father’s death, my 88-year-old mother began a romance with a religious hoarder she met at synagogue. Together they purchased a condo and signed a 30-year mortgage. For the next 10 years, I observed their blind optimism and uncanny enthusiasm with a mixture of delight and dismay.

“Was it right to intervene? If caregiving is about giving care, was it wrong to care more about my mother’s physical well-being than the fragility of this love affair? ”

The condo became an unlivable hoarder’s paradise just as my mother’s heart failure drove us to line up hospice. Then I became the monster who separated these nonagenarian lovebirds by taking her to my home. Perhaps I was rescuing my mother from pending catastrophe, but I was also stealing away her autonomy and her daily love life.

Was it right to intervene? If caregiving is about giving care, was it wrong to care more about my mother’s physical well-being than the fragility of this love affair? My mission was to pave the way for her peaceful death, yet I worried that I was now the source of heartbreak in my mother’s last days.

My mother’s relationship with Bill

This is a tale about a late-life romance in conflict with daughterly love and the complexity of caregiving. Looking back to when it all began, I wonder if my motive for the rescue stretched beyond the question of safety. It had taken a full 10 years for me to accept Bill and his many idiosyncrasies, and now I had an excuse to reject them at last.

Upon the loss of my father, to whom my mother was married for 65 years, the vastness of the grief we shared became the center of our already intense bond. My mother was in such a state of depression that I brought her to live near me in Massachusetts. In turn, my mother persuaded me to come with her to synagogue to say kaddish, the Jewish prayer for mourners; she had sought counsel from our local rabbi instead of the bereavement therapist I had recommended because she believed it would help us heal, despite our usual secular history. And it was here that she met Bill, who was also saying kaddish for his wife.

Bad enough I had lost my father, but as Bill persuaded my mother to join him at the synagogue daily, I feared I was losing the woman with whom I shared so much. She soon had at the center of her life a new job at the synagogue office, a new enthusiasm for conjuring up a minyan (a group required for specific religious obligations) and a new man who sounded a little like the punitive rabbi of my Brooklyn childhood when he scolded my family for coming to synagogue only once a year.

I struggled with Bill’s entry into my mother’s life, and consequently my own, because I could not imagine her with anyone but my father. And I needed her. She had always been my best friend, a savvy woman who listened well, loved me unconditionally and stood by me through any ordeal. Bill resented our weekly confiding sessions over breakfast because they didn’t include him, and I resented his resentment.

‘A new life’

Yet I came to realize my mother’s motivation to live on after my father’s death had everything to do with her new discoveries with Bill. I began to respect my mother’s courage in “choosing life,” as she put it, with the support of the synagogue community and her new mahjong buddies as well as the starry-eyed love of the only eligible octogenarian Jewish guy in town who could still drive. Their union gave my mother, as she put it, “a new life,” a second chance at loving and being loved in a partnership she had never anticipated.

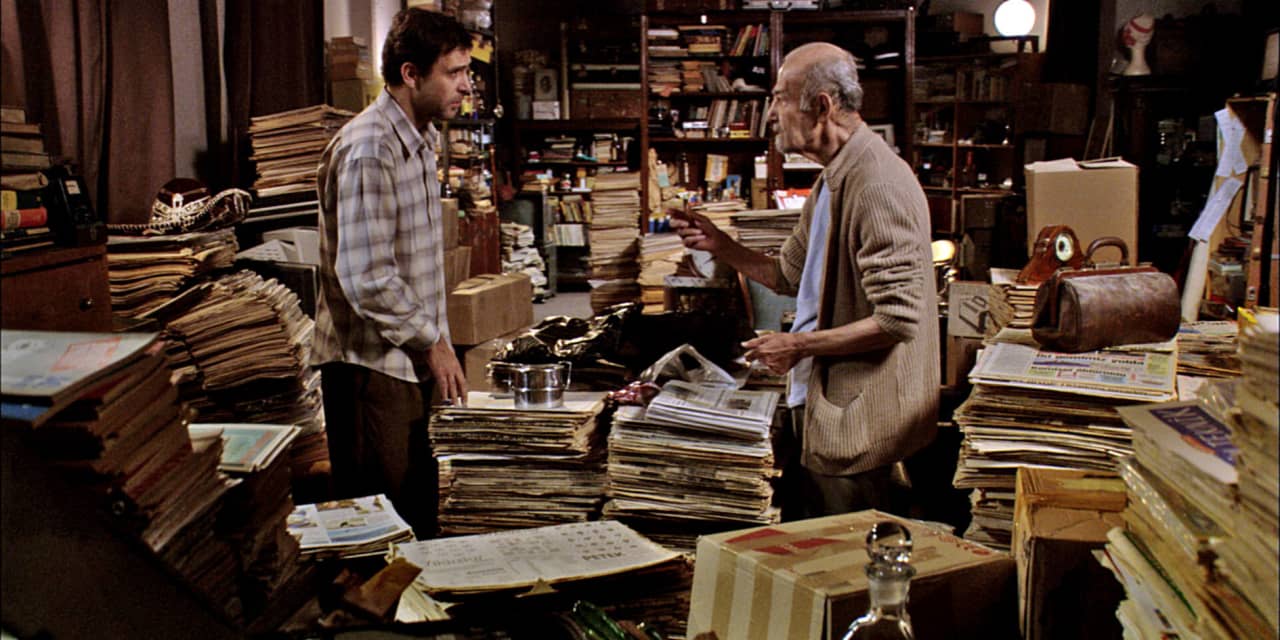

“Bill had a house of his own packed with objects of all kinds as well as a packed storage unit, but now the condo was the receptacle for a whole new accumulation of things large and small. ”

My mother treasured her renewed independence once she had moved out of our house and into the condo she shared with Bill. She could prepare dinners in her own kitchen, play piano and make as many mistakes as she’d like, charm Bill to their mutual delight, and feel like she was still young and free in her 90s. Further, Bill was a source of emotional support on cold wintry nights when he would reassure her that they could count on each other to survive against all odds.

I remember the thrill in my mother’s eyes when she spoke of Bill’s attraction to objects. Initially, she would block the doorway when Bill returned from one of his tag sale adventures, exclaiming “that’s not coming in here!” Then Bill would take out a plastic bag with this or that piece of costume jewelry “just for her,” and my mother would melt. Next time I’d see her, she’d be wearing the trinket and Bill would quickly say it only cost him a few dollars. Part of the delight was the bargain, of course, but part of it was the sheer love of pretty things, or things they saw as pretty.

Soon my mother joined in the madness. She would come home from Goodwill, an auction, or a tag sale, and tell me about the latest acquisition, this or that Lenox teapot for five bucks once worth $1,500 and this or that painting.

It had been strange to watch my mother’s steady transformation in the presence of Bill. She became increasingly radiant with each of their adventurous purchases. Of course, Bill had a house of his own packed with objects of all kinds as well as a packed storage unit, but now the condo was the receptacle for a whole new accumulation of things large and small.

At the end of their 10 years of companionship, years in which they attended concerts and lectures on nearby college campuses, sang boldly together in synagogue, produced the synagogue newsletter, got paid for this work, went to auctions and tag sales to spend that money and enjoyed lunches at the senior centers nearby, my mother’s health began to fail. She was 98 and Bill was 96.

You might like: I care for my mother, 90, and husband, 73. He contributes nothing. I work and pay all the bills. What hope do I have?

Hoarding out of control

Bill’s hoarding intensified once my mother’s heart condition worsened; she could no longer join him to stop at least some of the needless purchases. Despite the sea of statues lining the stairs, paintings, teapots, chachkas of all kinds, excess antique furniture and more, my mother still insisted stairs were good for her at age 98, but the stairs were an obstacle course even for the most physically fit. The nurses couldn’t get to her oxygen tank, let alone to her, without fear of injury.

As she became weak due to heart failure, she described how they would lie in the bed together and listen to classical music while holding hands. Then in the face of her pending death, hospice nurses refused to enter the condo, expressing concern about my mother’s safety in such a cluttered environment.

One evening toward the end, a nurse bumped into one of Bill’s Greek statues on the floor, and this caused a porcelain clown on the cluttered table just above to crash to the floor in a splash of colorful pieces. Bill had a tantrum, and my mother called me to come help her calm him down.

When I walked in, I saw that objects had vastly accumulated, now covering every inch of floor, table and staircase. My mother was struggling to breathe, and Bill looked both terrified and angry. I decided in that moment that I would convert my dining room on the first floor into a bedroom and bring my mother there for her final days. But I also knew that these were to be her last days with Bill, and I suspected that their love is what kept my mother alive up to this point.

I didn’t kidnap her right away. My mother asked me to spend the night and see how Bill was in the morning. Perhaps she thought I could help get rid of a few things so the nurses wouldn’t complain. But with one look at all the glassware, chess sets, stuffed animals and paraphernalia, I knew I was not equipped to do so, nor did I feel Bill could handle it. Even my mother was worried about her difficulty breathing and about Bill’s rage over the broken clown.

That night, I found my mother’s medication under a pile of sweaters and T-shirts from Goodwill, handed her the pill and a glass of water, and then moved her and her oxygen tank into the room across from the one she shared with Bill. I figured we’d the spend the night and reassess in the morning.

“Bill called me “Miss Ph.D.,” an “intruder,” and that’s exactly what I was.”

All the while, I repressed the thought that I was losing my mother. We were told there was nothing that could be done, that neither surgery nor medication could save her at this point. The person who had been my best friend until Bill came along, the one with whom I had shared my darkest secrets, was soon to die. But I had no time to dwell on that loss. I was too busy worrying about how my presence was being perceived.

I was the czar of order, attempting to change their lives, separating two old lovers from their last stretch of time in each other’s arms. I would be the source of my mother’s loss of autonomy and would be tearing her away from this man she loved. Bill called me “Miss Ph.D.,” an “intruder,” and that’s exactly what I was. Yet I saw no alternative.

My mother’s guest room, our bunker for the night, was another hoarding disaster. For us to get into the bed, I had to move countless papers, objects, small and large jewelry boxes, shirts, lamps without lamp shades and large velvet or plastic bags of costume jewelry aside. We figured we’d stay there until Bill calmed down.

I knew that his rage was not solely about the threat to his objects, but about the reality that he was about to lose my mother. She was dying, and in these final days, she would not be there by his side.

My mother had a bag of potato chips stashed under the bed. “It will calm us down,” she said, and we munched away while watching an old movie on the tiny TV set by the bed: Doris Day was flirting with Dean Martin in “Pillow Talk.”

I thought about how striking it had been to see my mother in a torrid romance in her 90s — her delight in flirting with Bill as he tenderly held her hand or caressed her shoulder. We shared some muffled giggling, thinking Bill was listening at the door as we discussed his hoarding obsession and consequent tantrum. How bizarre the whole situation had become! It was like we were in a bad movie, my mother said, hiding out, trapped in the guest room.

““She’s trying to split us up, Mollie. It’s me or your child. You decide!””

The whole sleepless night seemed endless. In the morning, Bill was waiting for us in the kitchen, still seething, but quiet. I explained that I had no choice, that I couldn’t leave my mother there with him if the nurse would no longer come. Bill glared at me and blurted out, “I can take care of her! We don’t need those clumsy nurses. How could you do this to us?” and to my mother, he said, “She’s trying to split us up, Mollie. It’s me or your child. You decide!”

The sadness of her final days

That last sentence was the turning point for my mother. She had always been and would always be my mother. No one could ever ask her to make that choice. She packed a little overnight bag. I held my mother’s hand with one hand and the oxygen tank with the other. It was clear her heart was breaking. While I was screaming inside at the thought of my mother’s pending death, their focus was only on their need to be together, warding off all the hardships of old age, let alone terminal illness and death.

On that nightmarish morning, I did move Mother to my home. I invited Bill to visit daily, but that wasn’t the same for him. It marked the beginning of the finality of loss. He was losing his housemate and, as he put it, the love of his life. My mother reassured him, despite the odds, that she’d be back, and nothing could part them. Sadly, hoarding did, as did her death in just a few days from our departure.

In those final days of my mother’s life, Bill visited and sat by her side. My mother, weak and short of breath, would make sure she was wearing her best blouse (a silk one Bill had purchased for her from the Salvation Army), some tasteful costume jewelry, large clip-on earrings, also a gift from Bill, and a dangling bracelet. Bill would not let her doze when he visited, telling her she could not allow herself to give in.

My mother seemed to join Bill in her resistance to her own frailty and the inevitable process of dying, or at least to let him persuade her to join in the fight. When I asked them to wait in the den while I prepared and then brought them lunch, Bill convinced my mother to rise and attempt to walk with him into the kitchen, using one walker. “Don’t let her turn you into a vegetable,” he muttered.

I heard a scream. Both Bill and my mother had fallen, and a wound on my mother’s arm had opened. She was bleeding profusely. I began to shout at Bill uncontrollably, “Get out of my house!” — and suddenly realized I was screaming at a 96-year-old man who had fallen. I checked that he was not injured and quickly sent him home.

Inevitably, my mother yielded, and so did Bill. She died the next morning. When Bill returned, he thanked me for not letting her die in a nursing home, as they both had feared could happen, and we forgave each other.

Now I remember my mother’s eyes when she anticipated Bill’s arrival, or the way she marveled at some of the objects he brought into their home. Of course, she would tell him to put things in storage rather than keep on cluttering, but she also loved to look at each new thing he purchased and made some purchases of her own.

My mother always loved to hear me play piano. It was thanks to her that I began piano study as a child. On the last night of her life, I played one of Schubert’s last sonatas, composed with Schubert’s knowledge of his impending death. For me, it summed it all up with its conflicting sounds: my love for my mother, the love between my mother and Bill, caregiving heartbreak — all that sweetness of life in the major key mixed with ominous shifts to the minor key. It captured the sweetness of love as well as the painful knowledge of pending loss that made the sweetness that much sweeter.

Also read: Nursing home? No thanks. 70% of people surveyed would rather not.

Perhaps their object acquisition was a way of fighting the good fight together. My mother had never been to an auction before she met Bill, but their mutual delight in new objects was exciting for her. Hoarding parted them on the brink of her death, but I realize now that their shared delight in new objects also united them in the belief that they could live yet one more day together to appreciate yet another shopping expedition.

Leah Blatt Glasser is professor emerita of English at Mount Holyoke College and the author of the literary biography “In a Closet Hidden: The Life and Work of Mary E. Wilkins Freeman” (University of Massachusetts Press, 1996). She is currently working on her memoir, tentatively titled “Between Sisters.”

This article is reprinted by permission from NextAvenue.org, © 2022 Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. All rights reserved.

More from Next Avenue: