This post was originally published on this site

The investment case for shares of growth companies — that their earnings will grow faster than those of value-style companies — is not supported by the evidence.

That was the conclusion of groundbreaking research 25 years ago that appeared in the prestigious Journal of Finance. And it also is the conclusion of new research that replicated the earlier study with the 25 years of data that have transpired since then.

It’s hard to overestimate the importance of those two studies’ findings. If growth stocks’ earnings per share (EPS) don’t grow faster than those of value stocks, then they must be overvalued relative to value stocks.

To illustrate, consider the SPDR S&P 500 Growth ETF

SPYG,

and the SPDR S&P 500 Value ETF

SPYV,

which contain the growth stocks and the value stocks in the S&P 500 Index

SPX,

The table, below, compares the projected EPS growth rates of the two funds’ holdings (per State Street Global Advisors, the ETFs’ issuer), along with their price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios. As you can see, SPYG commands a significantly higher P/E ratio because its component stocks are projected to grow significantly faster.

| Estimated 3-5 year EPS growth rate | P/E ratio | |

| SPDR S&P 500 Growth ETF | 14.32% | 20.56 |

| SPDR S&P 500 Value ETF | 9.69% | 14.12 |

But what if the growth stocks’ growth projections are too optimistic? In that case, there would be no reason to accept their much higher P/E ratios.

The study from 25 years ago — conducted by Louis K.C. Chan (chair of the Department of Finance at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign), and Jason Karceski and Josef Lakonishok (of LSV Asset Management) — found that “there is no persistence in long-term earnings growth beyond chance.”

The investment implication was that there’s no reason to pay up for high-flying growth stocks.

Many have questioned that conclusion, since value stocks in recent years have lagged behind growth stocks. Might the markets have changed in some fundamental way?

The monumental effort required to provide a definitive answer was conducted by two researchers at Verdad, the money-management firm: Brian Chingono, director of quantitative research, and Greg Obenshain, partner and director of credit. The two reviewed all U.S. stocks between 1997 and 2022 to cover the out-of-sample period since the original paper was published. “[W]e found little to no evidence of persistence in earnings growth, beyond chance, over the long term,” they concluded.

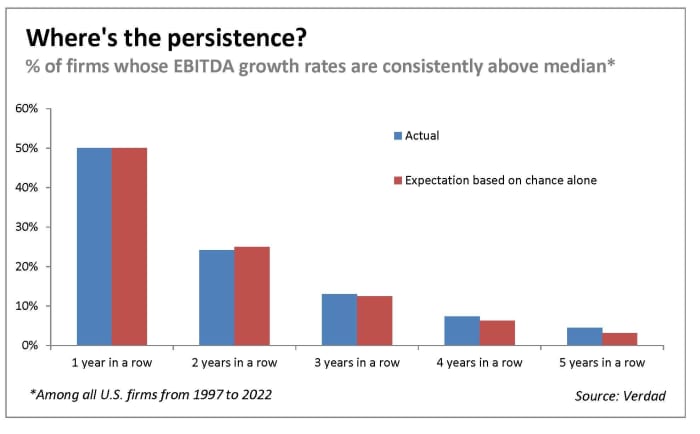

The chart, below, summarizes what Chingono and Obenshain found. It plots the percentage of companies whose growth rates of EBITDA (earnings before taxes, interest, depreciation and amortization) are above median in each successive year. The chart also shows what you’d expect these percentages to be on the assumption of pure chance.

For example, by definition you’d expect 50% of firms to have above-median EBITDA growth rates over the next year. If year-to-year growth rates were randomly distributed, you’d expect 25% of the firms to have above-median growth rates for two successive years (50% of the first year’s 50%). The actual percentage, based on experience over the last 25 years, was virtually the same — at 24.2%.

By the end of the fifth year, you’d expect just 3.1% to have had above-median growth rates for each year along the way. In fact, the researchers found, it was only barely higher at 4.5%.

The investment implications are many and profound. For example, you should take with a grain of salt the projected earnings growth rates provided by Wall Street analysts or from companies themselves. On average, growth stocks’ earnings do not grow any faster than value stocks’.

This doesn’t mean that growth stocks can’t outperform value stocks, I hasten to add. They very much can, as we’ve seen over much of the last decade. But this research indicates what must happen in order for growth stocks to outperform: Their P/E multiples must not only be higher than those of value stocks, but they must expand at a faster rate.

Yet P/E multiples can’t expand indefinitely. And when the music stops, growth stocks will crash and value stocks will outperform. That’s precisely what we’ve seen over the past year.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com