This post was originally published on this site

The Federal Reserve must do more to fight inflation in an economy radically changed by the pandemic, conditions in China, the war in Ukraine. and climate change.

Zooming and other collaborative technologies that enable more work from home are leaving offices half empty and downtown restaurants and other services with many fewer patrons. Urban zoning rules and limited supplies of buildable suburban land, construction materials and skilled labor have pushed up rents and suburban home prices.

Counterpoint: Leading indicators show inflation is slowing, but Fed policy makers are too busy looking in rearview mirror to notice

Globalization no longer a deflationary force

Western businesses are finding China a less attractive destination for manufacturing and investment. In parts, this owes to President Donald Trump’s tariffs that are now sustained by President Joe Biden, President Xi Jinping’s antibusiness machinations and clumsy COVID response, and the fallout from China’s real estate and financing bubbles.

Official data show foreign investment in China rising but a lot of that is domestic investment round tripping through Hong Kong. And Chinese manufacturers are pouring into Mexico to take advantage of its free-trade status with the United States where logistics are more difficult and labor costs higher.

Those and other diversifications of supply chains instigated by COVID bottlenecks reduce the downward pressures on prices and wages afforded by globalization in recent decades.

Even without a war in Ukraine, climate change and attendant droughts in North America, China and Europe would curtail agricultural production, hydro power and commercial river traffic.

Among the largest oil

CL00,

and gas

NG00,

suppliers, sanctions on Iran and Russia are not likely to be removed by a new deal on nuclear weapons or an end to the war in Ukraine. Biden has aggravated relations with Saudi Arabia and virtually shut down leasing on federal lands.

Large mismatch in skills

The most striking characteristic of labor markets is not low unemployment but rather the mismatch between the skills of the unemployed and what businesses need.

Consequently, as the unemployment rate has declined, the ratio of jobs offered to job seekers has hovered at historic highs. Unemployment may have to ratchet up to at least 6.5% for two years to adequately curb wage pressures on inflation.

On the demand side, Biden’s pandemic relief and infrastructure packages, the Chips Act, and student-loan forgiveness is adding about $3.3 trillion in new spending power on top of the trillions added by Trump.

Since the month before the pandemic began, retail sales are up 30%—8% after adjusting for inflation. That new demand far exceeds the capacity of the economy to produce additional goods and services.

In the 12 months ending in August, the headline CPI was up 8.3%—off its postpandemic high of 9.1% in June. Almost all the pullback was caused by a moderation in gasoline prices that won’t be permanent. Biden has been pumping large amounts of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to get him through the midterm elections and that is a finite resource.

And now for the bad news.

The Fed isn’t doing enough

The trend in all measures of core inflation—those that strip out volatile food, energy and sometimes items like used cars—continues to head up. At more than 6%, it could be stuck at a high level.

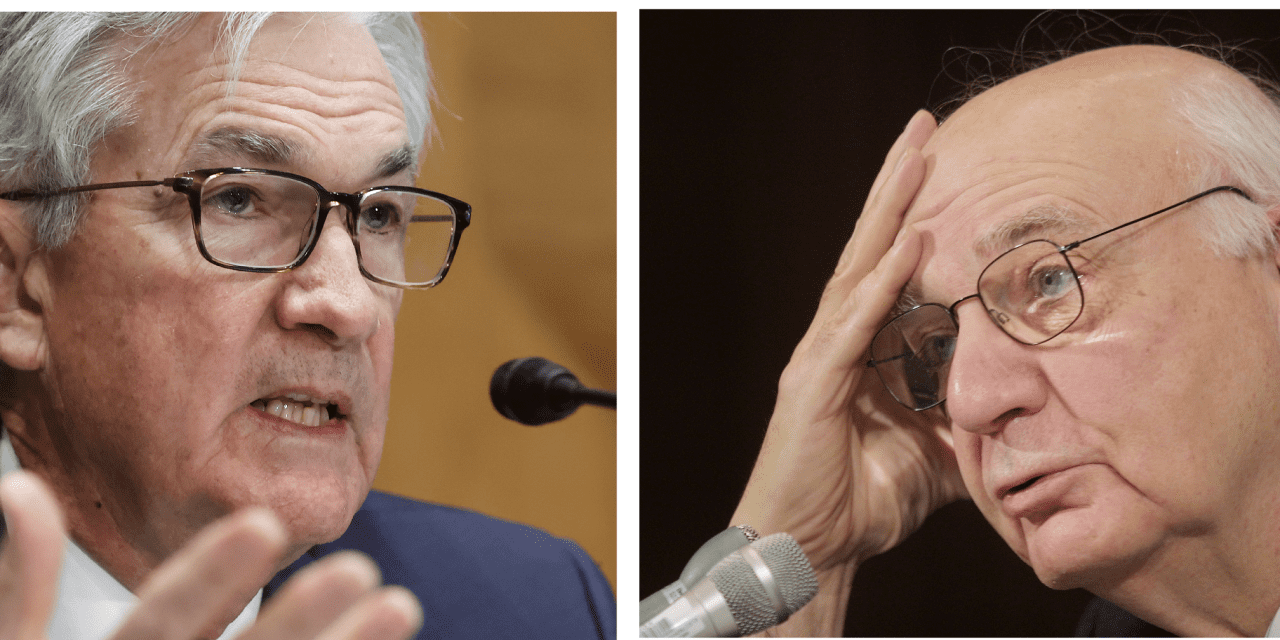

Against all this, Fed Chairman’s Jerome Powell’s policies are simply not enough. Since February, he has lifted the federal funds rate

FF00,

3 percentage points.

After taking the helm in August 1979, Paul Volcker raised the federal funds rate 6.7 percentage points in eight months.

Yet, Powell’s economy is beset by more structural problems. Both men faced troubling conditions in oil markets, but Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan were looking to enable domestic production not shut down drilling on federal lands.

Carter and Reagan were deregulating to lower business costs and boost competition, whereas Biden is going in the reverse direction. Add to these climate change and the shift to green energy, work from home, labor-market mismatches and the like, and Powell should be doing more not less than Volcker did.

Also, with $3 trillion sitting in household and nonprofit savings and checking accounts from excessive pandemic saving and Biden’s aggressive fiscal posture, raising interest rates and running down the Fed balance sheet are not having a huge impact outside the housing market.

The banks are losing deposits as households, nonprofits and businesses shift back into money-market funds and bonds

TMUBMUSD10Y,

However, consumers still feel richer and can keep on spending, and banks still have more deposits than they need to fund their loan books.

Facing a charging wild boar, Powell has eschewed his big rifle for a peashooter.

After Volcker’s initial volleys of rate increases, the U.S. economy slipped into recession in early 1980. He pulled back on interest rates but once the economy was on the mend, he really got religion and raised the federal funds rate to 19% in early 1981.

Powell needs to take those kinds of actions now.

Peter Morici is an economist and emeritus business professor at the University of Maryland, and a national columnist.

More opinions from Peter Morici

Americans want a president selling solutions, not a revolution