This post was originally published on this site

You start retirement with idyllic dreams about all the things you’ll now have time to do, plus maybe some part-time work and volunteering, and then, whammo: you’re suddenly thrust into becoming a caregiver for a parent, parent-in-law or spouse.

The best-laid plans…

There are a few things you can — and probably should — do to help yourself and your loved one if you’re a caregiver in retirement, as I’ll explain shortly.

Nearly one in five family caregivers are 65+, according to the AARP/National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) survey; Caregiving in the U.S. 2020. Most of them are assisting a parent, parent-in-law, spouse or partner.

Caregiving and early retirement

“Caregiving often can pull people out of the workforce a lot sooner than they thought and can cause a retirement earlier than expected,” says Meredith Stoddard, life events experience lead at Fidelity Investments.

For some caregivers, says Family Caregiver Alliance Client Services Director Christina Irving, “the cost of paying for in-home care ends up being more than what their income is” from working.

Caregiving led 15% of respondents to switch from full-time to either part-time work or reduced work hours, according to to the AARP/NAC survey, while 6% gave up work entirely and 5% retired early.

Spousal caregivers are more likely than parental caregivers to reduce their work hours, give up work entirely or retire early, according to a 2019 Government Accountability Office report.

But, Irving says, “most of the time, people aren’t prepared for what it means to be a caregiver.”

Work impacts as a result of caregiving

AARP/NAC caregiving report

How caregiving upended this couple’s retirement

Laura Wood and her husband John fit that bill. They retired about three years ago, moving from Virginia to sunny Pensacola, Fla., with great expectations. “We were hoping to spend more time with our three grown children who are spread out across the country and see my mother-in-law or have her come visit,” says Laura.

Two years after retiring, the Woods realized Laura’s widowed mother in New Jersey had developed memory problems requiring assistance. So, Laura’s mom moved in with them.

“I knew it would be a big change. I didn’t know how big of a change it was going to be,” says Laura. The responsibility, she adds, “sometimes is daunting — and the fact that you’re kind of on call 24/7.” In addition, she notes, the role reversal of essentially becoming your parent’s parent “just puts an emotional and difficult layer on things that can make it even harder.”

Laura’s mother lived with the Woods until May 2022; she now lives in a Pensacola memory-care facility, where Laura visits her four days a week. “My husband has said a few times, ‘You know, our life still revolves around her.’ And to an extent, that’s true.”

Jonathan Davis, CEO of the family-caregiver training platform Trualta, says: “We hear from people all the time who are entering what they expect to be a carefree time in their lives only to be thrown into caregiving seemingly overnight. Not only does their vision of retirement change, but their financial situation and mental state are impacted as well.”

Caregiving’s effects on caregivers

As a new report from the National Alliance for Caregiving and the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors noted: “Family caregivers face an increased risk of deteriorating health and financial insecurity.” Medicare generally doesn’t cover the cost of home care, so caregivers are typically on the hook — sometimes for thousands of dollars a year.

When you become a family caregiver, as 53 million Americans are, you might find yourself suddenly becoming a combination of financial planner, medical assistant and psychologist for your loved one.

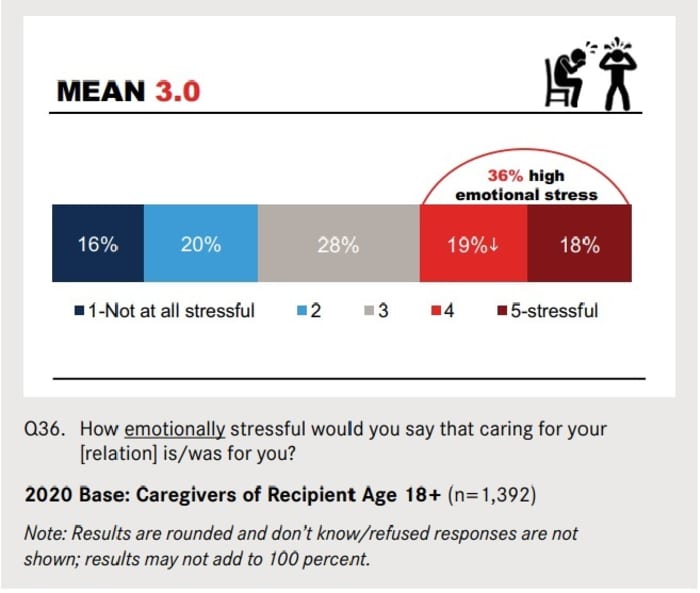

The role of caregiver, Kimberly Fraser writes in her forthcoming book “The Accidental Caregiver,” is “all consuming — physically, spiritually, and emotionally.” Some 36% of caregivers surveyed by AARP and NAC said caregiving meant “high emotional stress.”

Most caregivers AARP and NAC surveyed (53%) felt they didn’t have a choice taking on this responsibility.

“You don’t sit and say, ‘Well, you know, what are the pros and cons?’ You just do it,” says Susanne White, the author of “Self-Care for Caregivers” who was a caregiver for her parents.

The emotional stress of caregiving

AARP/NAC caregiving report

Finding meaning and purpose through caregiving

Being a caregiver, however, can also provide you with meaning and purpose in retirement. In fact, 51% of family caregivers surveyed by AARP and NAC said being a caregiver gave them a sense of purpose.

“There are a lot of positive aspects of caregiving, and it can be hard to remember those when you’re in the day-to-day of it and feeling stressed and overwhelmed,” says Irving. “But finding what purpose caregiving gives in your life can actually help build up resilience.”

You might find purpose by sharing the caregiving skills you’ve picked up with others earlier in their caregiving journey.

8 tips for providing caregiving in retirement

A few suggestions if you are — or will be — a caregiver during retirement:

Ask for help. “You can’t do it by yourself,” says White. “Really be honest with yourself and say, ‘I can’t do this’ and reach out to other people to say, ‘I need help.’” If you get help, she adds, you’ll be more rested and a better caregiver.

Start by enlisting family members and friends. A July 2022 Fidelity Investments surveyor caregivers of loved ones with disabilities or special needs found that 57% said supportive friends and family helped them most during the initial transition of serving as a caregiver.

“If there is some tension within your family, you may look at bringing in an outside facilitator like a case manager, therapist or someone from a faith community,” says Irving.

Finding support outside your family can be difficult, though.

“Caregivers who are retired may have friends and colleagues who are either still working or who are able to enjoy their retirement as they expected to,” Irving says. “So, they may not have that support network who understand what they’re going through and there can be some resentment that comes with that.”

In “The Accidental Caregiver,” Kimberly Fraserrecommends also searching online for local or virtual support groups with phrases like “family caregiver supports,” “caregiver support group” and “support group for caregivers of people with ____________.”

Notes Irving: “Caregiver support groups can be a great resource just to be able to commiserate with people who are walking a similar journey and can understand all the emotions that come with it.”

If you need assistance learning how to handle medical tasks for your loved one — from toiletry to wound care to administering injections to giving your loved ones medicines — ask a health professional. “Those are tasks people go to school for, but families end up just being given them,” says Irving.

In roughly 40 states, the CARE Act requires hospitals to provide the family caregiver with education and instruction of medical tasks they’ll need to perform for the patient at home.

YouTube may also have useful instructional videos.

Take care of yourself. “Many recent retirees experience a tremendous amount of stress from the physical and mental burden of caregiving and from their inability to experience what they’d been looking to,” says Trualta’s Davis.

Fidelity found that 70% of caregivers of loved ones with disabilities or special needs were so focused on caregiving duties, they put off addressing their own needs. But, Irving says, “taking care of your health is good for the caregiver and benefits the person they’re caring for.”

Self-care, White says, makes all the difference for you and for your loved one. “If you get sick, who’s going to take care of them?” she asks.

Fraser’s book suggests an assortment of self-care strategies ranging from going for a walk to practicing deeper breathing to calling a friend to taking care of your health. Repeat to yourself, she writes, “It is OK to take time for me.”

Set boundaries. That’s something many caregivers have trouble doing, says White.

“When you put boundaries up, you might think you’re a bad caregiver or not a good person,” she notes. “But especially when you’re retired and start taking care of someone, you need to make boundaries. Ask yourself: ‘What’s serving me so I can serve them?’”

Meet with the physician or physicians of the person you’re caring for. Fraser, a former nurse and a caregiver, suggests in her book asking the doctor questions such as: Where do I look for home care? and Where would I look for funding programs to help pay for medical equipment or supplies?

Your loved one’s doctor may authorize a visit from a nurse or physical therapist or occupational therapist who can teach you some skills you’re going to be providing day to day and if they’re considered medically necessary, they can be covered by insurance, says Irving.

Investigate national and local resources. The Family Caregiver Alliance offers webinars, classes and workshops for caregivers. The Alzheimer’s Association has a useful website and toll-free support line. Area Agencies on Aging can be helpful (find yours through the government’s Eldercare Locator).

Trualta has free caregiver education materials online for residents of 27 states, including an Emergency Planning Workbook; Wood used them and found them extremely helpful.

Look into the possibility of getting paid for your assistance. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, state Medicaid plans and some long-term-care insurance policies sometimes reimburse family caregivers. In some cases, loved ones needing the care pay family members for their assistance. Wood’s mother paid her and her husband a monthly amount toward the expenses of living with them.

If your loved one isn’t in a long-term-care facility but might need one someday, start researching local options. “My husband started to look at longer-term facilities for my mom five months before she had a stroke. And I’m so grateful,” says Wood.

Consult a financial adviser and an elder-law attorney. “There are a lot of unplanned financial challenges you come up against as a caregiver,” says White. “You start to spend money you weren’t expecting to.” A financial adviser can walk you through the potential effects of being a caregiver on your finances and an elder-law attorney can explain the ins and outs of Medicaid and essential caregiving documents such as power of attorney.

White also offers this reminder about caregiving: “You can’t do it perfectly. And there’s no rulebook. We’re really just there to walk each other home and make people we love feel safe and comfortable.”