This post was originally published on this site

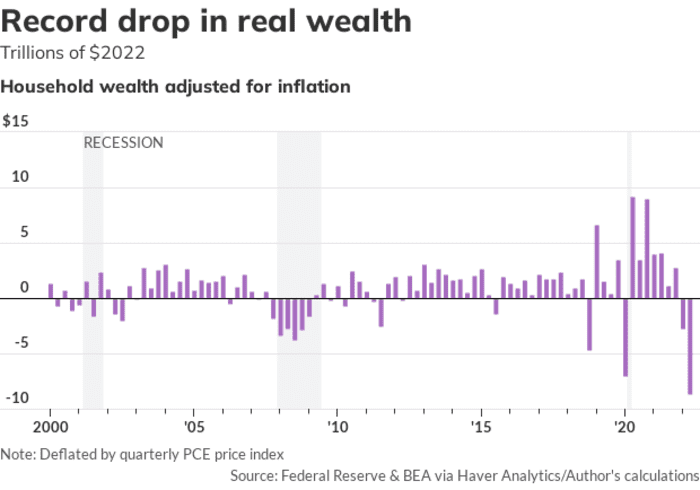

U.S. households’ real wealth plunged at a record 20.9% annual rate to $143 trillion in the second quarter of the year, with modest gains in home values offset by high inflation and a big selloff in the stock market

SPX,

COMP,

according to data released Friday by the Federal Reserve and analyzed by MarketWatch.

In current-dollar (or nominal) terms, household wealth fell by $6.1 trillion from March 31 to June 30, the Fed reported. But the real damage was worse than that because inflation was so high: After adjusting for the severe drop in the purchasing power of a dollar, the real (or inflation-adjusted) value of aggregate household wealth fell by a record $8.7 trillion.

The decline in wealth could have a significant effect on consumer sentiment and on the economy. This is a feature, not a bug, of Fed policy as it tries to slow the economy to fight inflation.

While the Fed doesn’t directly target stock prices, policy makers know that higher rates generally hurt stocks and that the loss of wealth on Wall Street is one of the main ways the Fed can affect the economy on Main Street. Consumer spending could be reduced by hundreds of billions of dollars over the next year via this wealth effect.

Since the end of June, the stock market is up about 7%. However, house prices fell in real terms in June, the latest month we have data for. For most families, housing wealth is more important than the stock market.

More on housing: Real house prices plunge after double-digit increases—but relief won’t show up in inflation reports anytime soon

MarketWatch

Wealth is defined as the value of all assets owned by U.S. residents (such as stock-market holdings, homes and bank accounts) minus the value of their liabilities (such as debt).

It’s appropriate to adjust household wealth for inflation, because what people care about most is what their wealth (and the income it generates) will purchase in the real world. When inflation is running high, asset values need to increase in nominal terms just to stay even.

Unfortunately, the Fed reports the data in nominal terms and does not adjust for inflation, in part because the Fed’s financial accounts release follows global reporting standards. Unfortunate because reporting the data in nominal terms distorts the reality of inflation’s impact on family wealth.

Over the first half of the year, Americans’ real wealth dropped by $11.5 trillion. Still, real wealth has risen about $15 trillion since the prepandemic level in the fourth quarter of 2019, a 4.5% annual increase.

For comparison, real wealth fell by $7.1 trillion (in 2022 dollars) in the first quarter of 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. During the Great Recession of 2008-09, real wealth fell by $16.1 trillion (also in 2022 dollars) over six quarters.

In real terms, household holdings of corporate equities and mutual funds fell by a record $7.4 trillion to $35.3 trillion in the second quarter, the Fed reported. At the same time, the real value of real estate rose by $771 billion to $41.2 trillion as house prices continued to rise faster than overall inflation.

MarketWatch

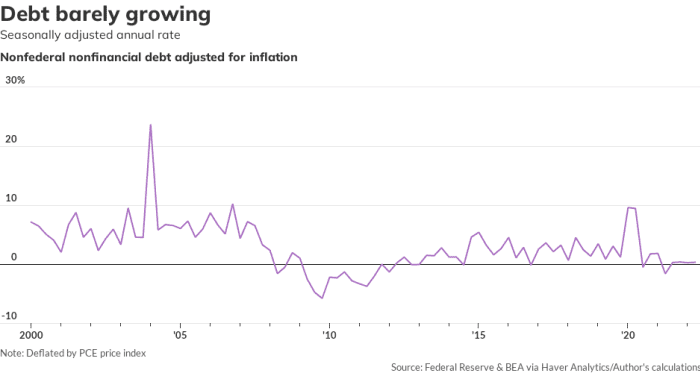

The quarterly financial accounts report also indicated that real nonfederal nonfinancial debt rose 0.3% in the second quarter and is up 0.3% in the past year.

That’s a vital statistic for monetary policy, because the Fed is raising interest rates

FF00,

in order to slow the growth of borrowing as a way to reduce demand and quell inflationary pressures. It’s apparent that real debt growth by households, businesses, and local governments is extremely slow and has been for the past two years.

Rex Nutting is a columnist for MarketWatch who has been writing about the economy for more than 25 years.

More: A surging U.S. dollar is already sending ‘danger signals,’ economists warn

Plus: Learn how to shake up your financial routine at MarketWatch’s Best New Ideas in Money Festival on Sept. 21 and Sept. 22 in New York. Join Carrie Schwab, president of the Charles Schwab Foundation.