This post was originally published on this site

China’s recently reported record-breaking 20% youth unemployment rate has obscured an equally worrying trend among its younger generation: Even those employed are increasingly burned out and “quitting while remaining in the office.”

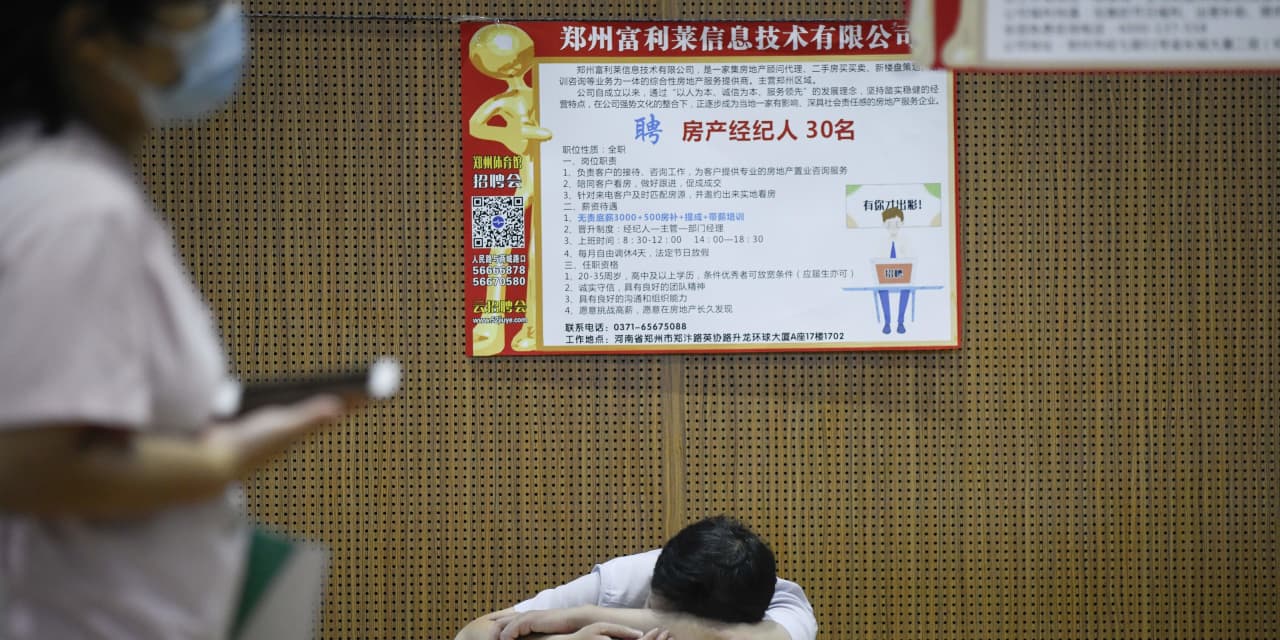

The headline-grabbing news last week that China’s unemployment rate for those aged 16-24 hit a never-before-seen high for the country, at 19.9% — meaning one in five youth cannot find work — was an unwelcome addition to the country’s array of economic difficulties.

COVID outbreaks have continued to plague the economy, largely because President Xi Jinping has mandated that containment of the virus is paramount regardless of the damage it continues to do to consumption, factory activity, tourism and other drivers of growth.

A severe property crisis and the government’s unwillingness to unleash large-scale stimulus measures have compounded matters. Nearly all leading analysts forecast China’s 2022 economic growth to be far below the government’s original target of 5%.

Layoffs, particularly among tech companies, have been going on for months. Regulatory crackdowns, weak consumer demand and a faltering economy overall have fueled the trend.

In March, the Wall Street Journal reported that Tencent Holdings

700,

and Alibaba Group Holding

BABA,

— huge employers of young tech talent — are both likely to lay off thousands of workers by the end of the year.

Neither company responded to requests for comment.

“But they [layoffs] are probably getting more attention now because they are gaining momentum due to growing economic woes related to China’s strict COVID control measures,” said Doug Young, director of Hong Kong-based Bamboo Works, which provides analysis on Chinese companies listed in Hong Kong and the U.S.

“What’s more, many of China’s fresh grads that would have normally gone to these companies to work are no longer finding such employment, which is in focus as the country reports its highest-ever youth unemployment rate,” he told MarketWatch.

A long-accepted finding from economic data is that low unemployment and high demand for workers gives existing and potential employees bargaining power, better wages and faster transitions to more attractive positions elsewhere.

This phenomenon has been taking place in the U.S. this year, according to the Roosevelt Institute.

The flip side generally is true as well: As with China at the moment, with huge pools of unemployed youth, and weak demand for new employees, companies have the upper hand.

This comes at an already disillusioning time for younger workers.

One 26-year-old woman in Beijing surnamed Zuo, who graduated from China’s prestigious Renmin University but works as an office assistant at a mid-size tech company, was asked her thoughts on her current employment.

“Wage slave,” she tersely responded.

When asked to elaborate, she said that the hours, conditions and her feeling of leverage have never been good there, but they’ve gotten worse throughout the year.

Chinese state media described “a prevalent sense of being stuck in an ever-so-draining rat race where everyone loses.”

China’s tech sector has long been known for its infamous “996” work culture — that’s working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week.

The exhaustion has fueled a raft of new terms to encapsulate the generation’s despair.

“Involution” emerged in 2020 to describe going nowhere or gaining nothing regardless of your work effort. “Lying flat” — leaving the hustle culture and “coasting” at your job — recently gave way to “let it rot,” which denotes a more active embrace of apathy in the workforce and indifference to repercussions that may follow.

While some of this echoes the “Great Resignation” in the U.S. during the pandemic, China’s employment situation is much more dire and the conversation surrounding these terms — when not censored — has garnered billions of posts on social media and have been among the top most-searched on China’s internet.

The implications of youth unemployment and giving up on climbing the occupational ladder have implications for China’s already weak consumption, tech culture and the coming demographic crisis in which younger Chinese will be expected to support China’s rapidly aging population.

But on the ground, it is simply a matter of despondency.

“All of my close friends went to college in good schools in the West,” said 24-year-old Chinese Yang Jing, who is in graduate school in Australia. “But when they returned to China, they could only get jobs if their parents were connected and pulled strings, or menial jobs that required overtime without overtime pay,” she said.

“And those are just the ones that secured some form of employment,” she added.