This post was originally published on this site

Two-plus years of COVID-19, and people are thinking differently about viruses.

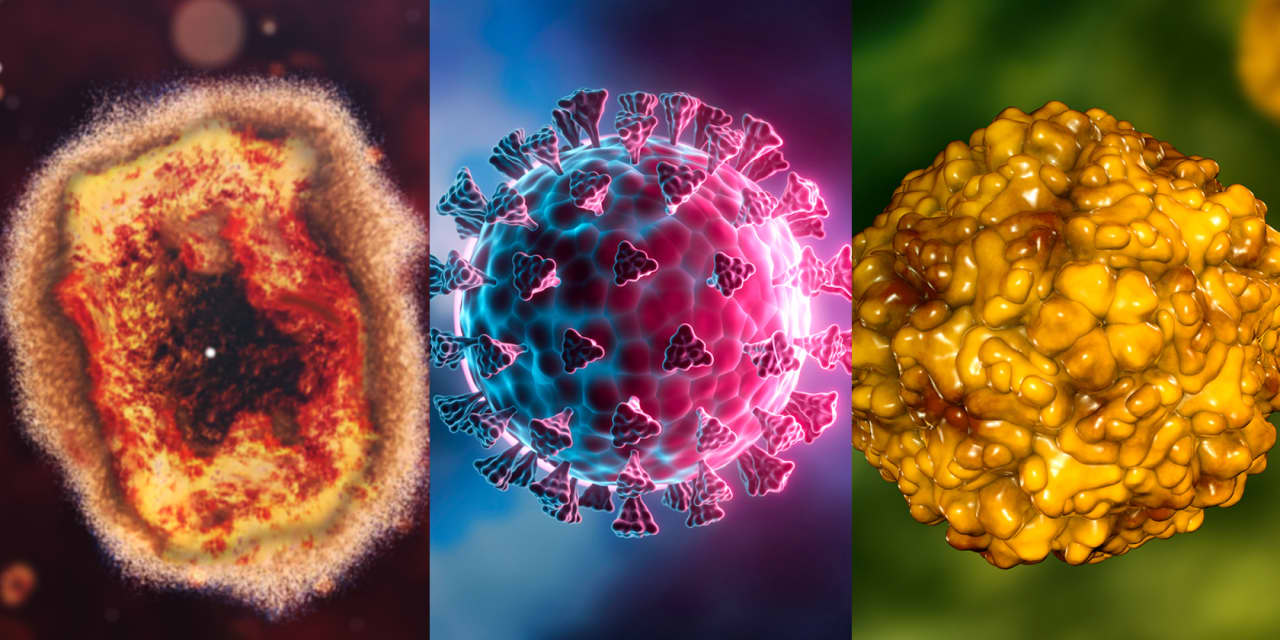

The U.S. this month declared monkeypox a public health emergency, and people at high risk of getting the virus — particularly men who have sex with men — are lining up in city streets to get vaccinated. An avian flu outbreak that pushed egg prices higher is finally winding down. Polio reemerged in New York. And then there’s SARS-CoV-2, which is still infecting about 93,000 people a day in the U.S.

“There is heightened focus on these types of outbreaks and diseases,” said Chris Meekins, a healthcare policy analyst at Raymond James. “Where we have been historically, it’s just the attention is greater.”

There are several factors that help explain some of the activity we are seeing. Research suggests that climate change and shifting land-use patterns could create a higher risk of viruses jumping from animals to humans. Some people are hesitant to get themselves and their children vaccinated. And it’s become clear that public-health bodies have to rethink the way they approach outbreaks.

Just last week, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, called for a reorganization to the public-health agency.

“It is time for CDC to change,” she told employees, according to the New York Times.

For now, however, the focus is on encouraging vaccination, whenever possible.

Though some people are increasingly hesitant to get vaccinated, the pandemic has also slowed utilization of medical services, and that includes childhood immunizations. A study published last year in JAMA Pediatrics found the rate of infants, children, and teens in the U.S. who were up-to-date on their vaccinations was lower in the fall of 2020, compared with 2019. By the end of 2020, the World Health Organization issued a call to push forward with measles and polio campaigns worldwide despite the pandemic.

“This is a wake-up call,” said Dr. Peter Salk, president of the Jonas Salk Legacy Foundation and the son of Jonas Salk, the developer of the polio vaccine, before noting: “I don’t think that people have to start to wave red flags and run urgently to this place or that place.”

That said, Salk recommends boosters for people who are at high risk of a polio infection. (This is the same as the CDC’s recommendation.)

Polio is in New York.

New York health officials last month reported a case of polio in an unvaccinated resident of Rockland County, which is north of the Bronx borough of New York City.

They also said that poliovirus, which causes paralytic polio, has been detected in the wastewater in New York City. It’s also been detected in the wastewater in Rockland and Orange counties, both of which have polio vaccination rates among 2-year-olds that are far below the state average of 78.9%. The state data excludes New York City as of Aug. 1. Orange County has a rate of 58.7%, while Rockland County has a 60.3% rate.

Dr. Mary Bassett, the state health commissioner, has described the wastewater surveillance data as “alarming, but not surprising.”

Polio vaccines, which have been around since the 1950s, are included in the childhood immunization schedule. However, only 86% of New York City children between the ages of 6 months old and 5 years old have received all three doses of the polio vaccine.

“The problem you face and why polio and other diseases like that are probably going to become a little more prevalent is you really have had this politicization of vaccines, this politicization of public health activities, to the point that there is a group of the population that’s just like, we’re not going to listen to that anymore,” Meekins said.

Monkeypox is now a public health emergency in the U.S.

Within months of the first warnings out of Europe, more than 14,000 people in the U.S. have been diagnosed with the poxvirus, which was first detected in 1970 and has been endemic in parts of Africa, as of Thursday. About 40,000 people worldwide have tested positive, and 12 have died.

Unlike SARS-CoV-2, however, the U.S. already has vaccine and treatment options for this virus. There are two shots: Bavarian Nordic’s

BAVA,

Jynneos, and Emergent BioSolutions’

EBS,

smallpox vaccine, ACAM2000. Antivirals that treat smallpox like Siga Technologies’

SIGA,

Tpoxx and Chimerix’s

CMRX,

Tembexa are expected to be effective against monkeypox.

Though Wall Street analysts say they don’t expect monkeypox to become a health concern for all Americans, the outbreak has raised further questions about how the U.S. responds to virus threats going forward.

“How will public health apply the lessons from COVID to shape a more effective response to monkeypox and future public health crises?” Cowen analysts wrote in a note to investors last week.